Missouri Horses and Mules

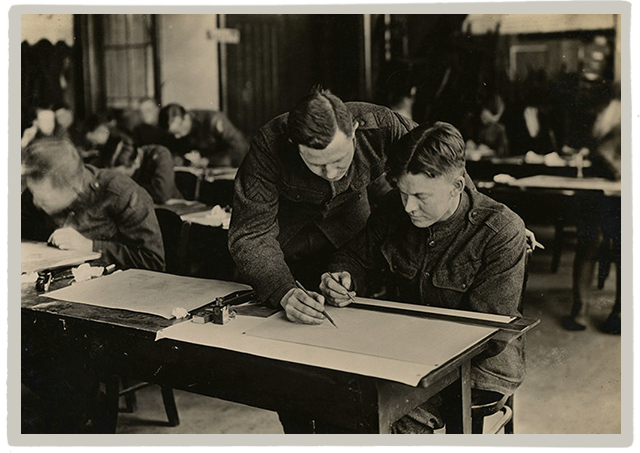

Soldiers and mule - n.d.

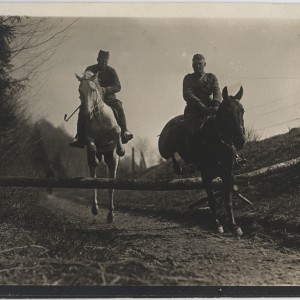

Although rapid technological innovations in the early twentieth century revolutionized warfare, World War I armies still relied heavily on horses and mules for transporting equipment. A seemingly insatiable demand for livestock by the Allied armies made the sale of horses and mules one of Missouri’s greatest contributions to the war effort. In fact, the large supply of farm stock in America proved to be a crucial advantage for the Allies. In 1914, Germany had 4 million horses and mules. England and France together could only muster 6 million, but America had 25 million. 1

Despite the availability of trucks, there were several reasons why commanders still depended on animal power to move men and equipment in World War I. Trucks became less reliable the closer they got to the front. The vehicles were prone to breakdowns and they were difficult to navigate on muddy roads in forward areas. Mules however, could easily maneuver on the war torn landscape of the Western Front. Strong and agile, they carried heavy loads for long distances and their surefootedness was legendary. Animals, just like soldiers, endured harsh privations during wartime, but mules recovered from intense exertions quickly and could even subsist on vegetation when grain and hay was not available. Troops in the trenches received most of their supplies, including the all-important hot meals, by mules. Even tanks, one of the most recognizable symbols of modern warfare, depended on mules for their ammunition and gasoline. 2

Just because mules could carry supplies to the front does not mean the columns moved smoothly, especially when accompanied by advancing troops. The movements took place at night to prevent detection by the enemy, which only added to the difficulty of navigation. Sergeant Willis B. Bridges described one such march from the St. Mihiel front, “ammunition trains with mules for motive power cant travel on a little skinny road in th’ dark with Yankees on foot. And cept’ for bein’ wet and hungry and havin’ sore feet and a awful heavy pack and dodgin’ mules’ heels and ole trenches and tryin’ to see in the dark wit’out a cats eyes and tryin’ hard to keep in sight of the guys ahead so we would’nt git lost, we was gittin’ ‘long lovely.” 3

Guyton and Harrington, a Missouri firm, had a lucrative contract with the British army for horses and mules. Founded at Lathrop in the 1890s by cousins J.D. Guyton and W.R. Harrington, the company became the largest mule dealership in the world. By 1918, they had 18 buildings on 4,700 acres of land with 150 men maintaining up to 50,000 mules. The company had done business with the British government during the Boer War in 1899-1902. Anticipating another war, the owners kept fertile land for future use and were thus able to meet the demands imposed by the Great War. Guyton and Harrington sold 180,000 mules to the British army from 1914-1918. This represented about one half of all mules shipped from America during the war. They also sold 170,000 horses to the British, which accounted for about one third of their purchases in America and Canada during the war. 4

Located in the southwest corner of the state, Springfield also became one of Missouri’s most prominent livestock centers. On June 28, 1914, ironically the day Archduke Franz Ferdinand and his wife Sophie were assassinated, the Springfield Republican reported on the city’s thriving mule industry. Six mule dealers were located on Convention Avenue. Many of their animals were raised on local farms, but the companies also purchased livestock from southeast Kansas, Oklahoma, and northern Arkansas. They had customers from as far away as Delaware and San Francisco. The local market faced an unprecedented demand for animals as war engulfed Europe. 5

Of course the sale of animals was dependent on the Allies ability to pay. Delays in processing a loan to France caused a major bottleneck at Springfield in October 1915. Two representatives of the French government had already purchased 700 horses that month. After these were shipped to Virginia in 30 boxcars, the agents continued buying from 48 dealers who had descended on Springfield. They bought another 500 head, but when negotiations on a loan to the French government broke down, the animals were held for two days at the Frisco rail yard. After the one half billion dollar loan to France and England was finalized, another 25 boxcars rumbled out of Springfield loaded with horses. The average sale price was $150 a head and local dealers received $82,000 from the lucrative trade. 6

While the livestock trade in Springfield flourished throughout the war, it fluctuated according to market demands. The peak seems to have been in 1916 when over 14,000 horses and mules were shipped from the “Queen City.” Their estimated value was $2.5 million. Ironically, this number dropped to 10,000 in 1917, the year America entered the war. At least part of the downturn may have been because the British stopped buying horses in May of that year. Also, while most of their orders were for the war effort, livestock dealers also sold animals to the South where they worked in cotton fields. This business began to decline as farmers turned to truck power. 7

Even though American farmers provided the Allies with thousands of mules before the United States entered the war, it did not hurt the supply of animals available to the American Expeditionary Force (A.E.F.) in 1917 and 1918. More than enough mules were available for overseas service; however, American commanders lacked the cargo space to get them across the Atlantic. In September 1917 the American army had 35,068 trained mules ready for shipment. Until the end of the war, only 29,910 sailed for Europe. The Americans ability to care for the animals in the war zone was likewise haphazard. Incredibly, there were no veterinary services in the A.E.F. and this lack of care had a devastating impact on the livestock shipped to France. Approximately 76% of mules in the A.E.F. died as a result of inadequate medical services. Concerned such chaos would spread disease among their own animals, the British and French had to care for the American’s animals in addition to their own. 8

The A.E.F. also relied on livestock from its allies to participate in the Meuse-Argonne offensive. To ensure American participation in what became the last offensive of the war, the Allied commander Ferdinand Foch transferred 13,000 animals to the A.E.F. for its movement from St. Mihiel. Even though this brought the number of animals laboring for the Americans up to 90,000, it did not solve the crushing supply problems faced by the army. Unfortunately, no additional animals were available, despite General John J. Pershing’s repeated requests. 9

More animals were always needed due to the horrific conditions livestock endured at the front. Periods of intense shelling could inflict multiple casualties among men and animals as described by Michel Sullivan, a soldier in Battery A, 129th Field Artillery. After almost 50% of his unit became casualties in the first week of the Meuse-Argonne offensive, the Germans shelled their position with high explosives around midnight on October 2. Throughout the night, trees struck by the shells rained down in splinters on the men. The fire was so intense artillery reinforcements from the 1st Division failed to reach their position three times. Sullivan wrote the next morning “the little valley presented a grewsome sight. More than a hundred horses were killed on the picket line, and in some places they had fallen in heaps, one on top of another.” 10

The A.E.F. likely used 600,000 animals during the war but the surplus was quickly sold when peace came in 1918. A total of 121,465 horses and 56,207 mules were sold in Europe after the war. Thousands more were sold in America within six months of the Armistice. These animals and those who did not survive made an invaluable contribution to the Allied victory. Horses and mules were an essential part of the lifeline for armies fighting a modern industrial war. Appreciation for their contributions did not go unnoticed, especially among the British who bought so much Missouri livestock. As a correspondent wrote, “The much maligned, supposedly stubborn, balky, and generally pestiferous mule, has won a place in the heart of the British Army from which he can never be dislodged.” 11

1 Melvin Bradley, The Missouri Mule: His Origins and Times, Volume 1 (Columbia: University of Missouri, 1993), 183, 188.

2 Emmett, M. Essin, Shavetails and Bell Sharps: The History of the U.S. Army Mule (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1997), 4, 152-53.

3 Willis B. Bridges, History of Company D, 314th Engineers, 61-62.

4 Bradley, The Missouri Mule, 183, 188.

5 “Springfield Is Some Mule Center,” Springfield (Mo.) Republican, June 28, 1914, 16.

6 “French Buy Many Horses In Ozarks,” Springfield (Mo.) Republican, October 16, 1915, 2; “Hundreds Of Army Horses Held Here By Disagreement,” Springfield (Mo.) Republican, October 21, 1915, 1; “Special Train Is Required To Ship Horses Held Here,” Springfield (Mo.) Republican, October 23, 1915, 1.

7 January 11, 1917, 2.

8 Essin, Shavetails and Bell Sharps, 150-51.

9 Essin, Shavetails and Bell Sharps, 154.

10 Michael Sullivan, Boxcars and Billets: Occasional Extracts From the Diary of an Echelon Soldier (Kansas City, Mo.: John A. Shine Publishing, n.d.), 10-11.

11 Essin, Shavetails and Bell Sharps, 156

Author

Michael Price

Michael Price is a Local History Associate at the Springfield-Greene County Library. A fo…

Learn more

Related Articles

Related Collections

Smith, Richard Thompson Collection

Richard T. Smith joined Company A of the Signal Corps, Missouri National Gu…