John H. Thacher letters to Pards - October 7, 1918 - December 6, 1918

Transcript

October 7, 1918. Such a good bunch of letters has just come in from the office and folks at home that I will try to be decent and work up a semblance of a reply. I suppose our part in the fighting has been about like anybody else’s experience but it is some satisfaction to remember that the gruff old General who commands this Brigade said to be when I was back at Headquarters for orders: “You stiffened the like; your battalion stiffened the line!” Our part in the great push was so small that nobody will ever notice it, but to us it was full of action. First there was night after night of long forced marches; nights when men and horses dragged themselves through rain and mud; when men fell face up in the road and slept at every halt; when horses were tortured to death and left by the roadside; when one slept in the saddle and lurched from stirrup to stirrup. Then, one night I was hustled on ahead with instructions to pick the battery positions. It was pouring and dark and we had a short time to figure “marks” and “defilade” and ranges. It was a position on a mountainside. We had dugouts (free from “cooties” for a miracle). In some of the positions the pieces had to be dragged up by ropes. We got in safely and had a little shell fire to keep us interested as we did it. Then came the night of the Big Push from the sea to the Swiss border. We were in on the barrage. It was a great sight. I do not suppose there ever was before such a concentration of artillery fire. It was almost the wheel to wheel stuff you read about. We cut barbed wire first and then passed on to the creeping barrage which precedes the infantry advance. The thing that impresses you is the one continuous note of it. No punctuation but just one uninterrupted roar and lightning glare. I got down into the gun-pit and got the number one man to let me take his place – just for the satisfaction of firing myself and tossing my personal regards over to the Baby Killers. After the barrage was over we limbered up and started out on the advance. News came that our infantry had taken 7 kilos of hard ground right through the Hindenburg line. The roads were muddy and choked with guns and trucks and traffic. Litter bearers with wounded and squads of German prisoners began to dribble back. Finally we came to the barbed wire and trenches and could hear the pop pop of machine guns. Just as our big lumbering battalion wagon was making the turn, there came the whish of a shell and there was a spout of earth and a jumble of harness and horses and men. I did not see how anybody could have escaped. But when I rode up it was only a horse or two and one man slightly fringed. I though the Boche would open up on us then with full effect; but with one of the usual lapses of stupidity that we can always count on in the Hun to help us out, they ceased fire for the time being. Probably had some mathematical schedule or table that required just so many shots at such and such an hour and then quit. We were still out in the open and as the column moved painfully forward, we remained in the open for six hours. Later at about five o’clock when the column was blocked by a big mudhole, Fritz checked up his schedule and started in again on us. I stood near Gates and saw one shell go on one side of the creek near us, then one on the other and thought, “Well, the next is our own baby!”, but it fell way down the column. I don’t know how we got through but we did at last and got the horses and men to cover about 1 A. M. Next day Major miles and I went up on the hill ahead to establish a forward [page 1]

Description

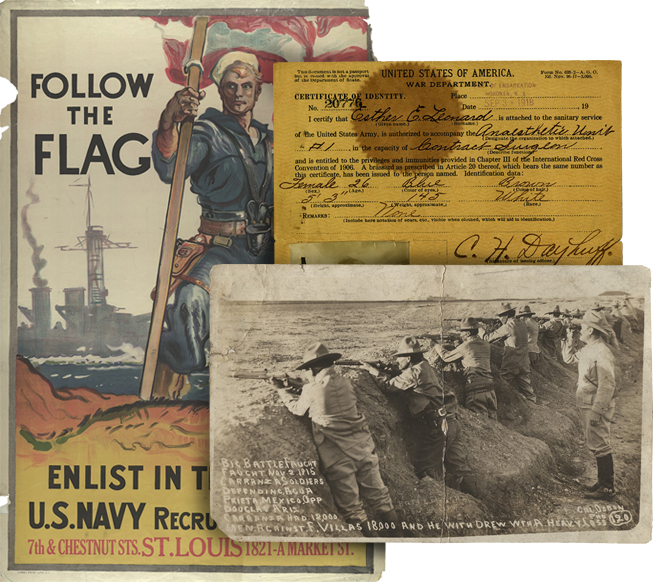

Captain John H. Thacher of the 129th Field Artillery wrote from the front lines to his law partners in Kansas City, Missouri describing the movements of the Army in France. He describes the advancement of his troops and a German dugout that him and his men captured. Before the war, Thacher worked as an attorney with the firm Rozelle, Vineyard, Thacher, and Boys. He served on the Mexican Border and was later drafted into the Federal Army as Captain of the 129th Field Artillery. After Harry S. Truman took command of the 129th Field Artillery, Thacher was appointed adjutant of the 1st Battalion of the 129th Field Artillery , and later assumed command of the 110th Ammunition Train of the 35th Division.

Transcript

Observation Post. We went into the German dugouts. All was confusion and jumbled papers and property. You have to be durned careful. They wire the things and when you lift a stovepipe or a helmet or a chair, it explodes a mine. Shooed all the men away and cleaned the place out myself. Had some emotions especially in handling some little glass tubes called detonators – which I took out and buried. We put in our phones and spread out our maps and opened fire ahead of our infantry. That night we had the pleasure of sleeping in captured German dugouts, eating captured German food warmed over captured German solid alcohol, talking over captured German phones, all of which were substantially but stupidly made. I began to understand something now of the “position” or “trench warfare”, both sides dug in – had comfortable electric lighted dugouts – (in one German dugout it is an actual fact they had a porcelain bath tub) – they had leave energy three months, wine, good food – why should they raise h- -l to change the situation? The fool American bursts in and says, “To h- -l with your trench and dugouts. We’re here to win the war. Let’s mosey on!” And he moseys, believe me! I saw my first dead man next day. Had seen so many men exhausted lying asleep in all sorts of grotesque attitudes that when I came to this one lying back in a shell crater I thought it was some tired doughboy, fallen asleep behind the last charge. Then I saw the red blotch between his eyes. There were others and others. And Germans, too. Some firesides in Dusseldorf and Munich and Berlin are going to know that there is something behind “American Bluff”. Well, it was next day our real action began. We were ordered out at daybreak to take up a position at either C or B. I led the battalion out while the Major worked on getting the column straightened out. In the road were crowded trucks and ammunition trains and doughboys and Red Cross ambulances. I cut away from the main road as soon as I could but just as our last battery was coming over the hill, The Boche opened up on us. They got a bracket on us and unpleasant things happened although our damage was slight. Our guns wheeled into action and opened fire on a German battery back in the woods. We knew things were pretty warm up ahead and we were well up with the infantry and the tanks, which were waddling along the road beside us. I noticed a troop of cavalry coming back and a French battery withdrawing. I thought that curious. Wounded officers came in bleeding and excited, trying to tell us where to put our fire. I got the 8 drop switchboard in, put out the wires to the batteries, sent a man to ransack the German command posts for maps and papers with information as to their positions. Then I began to realize just about how we stood. We were out on a limb. The divisions on the right and left had not kept up with our advance and we were being raked by flank machine gun and shell fire. Our guns were in a steep narrow valley. We couldn’t withdraw and we were about up to the infantry second lines. We were right at a cross-roads well known to the Germans. And to sum it all up, I afterwards heard the General of our Brigade tell our Colonel that the situation was ticklish and he had been worried about us. But the doughboys poor devils needed support and we just had to stick. Guess we didn’t really know either what we were up against. Changed the Command Post to a dugout that was protected on one side and open on the other. One shell struck square on top of it – one a few feet in front of it, but didn’t hurt anyone. My only bit of excitement was taking a wire forward and establishing an observation post in the infantry trenches. There was a little shell fire going on at the time, but it didn’t come anywhere near me. Got the wire through all right and put up my monocular scope in the doughboy trenches, but couldn’t locate the flashes of the battery that was firing on me though I tried for two hours. Went a few feet away to a dugout where the General was; crawled down a dark hole to a candle lit den full of maps and he was just showing me our targets when news came that Germans had broken through on our right and were only a kilo away. He closed the Headquarters, but I got my targets from him, went tearing back to my phone in the trenches to phone down and open fire – when the wire was shot out! Got back safely, found batteries under fire. One shell struck between piece and caisson in one battery. Well, we had it hot for six days that way and when we were ordered out, came out under fire. We are resting up now. Don’t know where they will send us next. [page 2]

Description

Captain John H. Thacher of the 129th Field Artillery wrote from the front lines to his law partners in Kansas City, Missouri describing the movements of the Army in France. He describes the advancement of his troops and a German dugout that him and his men captured. Before the war, Thacher worked as an attorney with the firm Rozelle, Vineyard, Thacher, and Boys. He served on the Mexican Border and was later drafted into the Federal Army as Captain of the 129th Field Artillery. After Harry S. Truman took command of the 129th Field Artillery, Thacher was appointed adjutant of the 1st Battalion of the 129th Field Artillery , and later assumed command of the 110th Ammunition Train of the 35th Division.

Transcript

October 12, 1918. The Q. M. wagon has just rolled in and has taken up some of the capital you invested. So I will drop you all a line or two to let you know where the kindly touch of your helpful donations is being felt. We are just in from the front. We are hove up in billets to rest and sleep and get new clothes and horses and blankets and canteens and mess-kits and such stuff to make up for what we have distributed over the landscape of France in our last campaign. Our men have been twice at the front and have all of them had a good stiff drink of the Game of War. I think that it’s the “morning-after” sensation we are suffering from now. Part of our bunch went into position under shell fire on the last drive and were under fire from flanking Boche batteries for some five days. We were up with the infantry second lines. As one of the boys expressed it: “We couldn’t have been any forwarder without charging the Boche with our limbers!” At such times roads are blocked; supply trains delayed; columns are caught under artillery fire and the ration wagons somehow don’t get up. Grub runs low and worst of all, tobacco gives out. It’s then that the good friends from the little village on the Missouri and Kaw step into the breach. A carton of precious cigarettes is dragged out from its hiding place in a fourgon; some canned milk helps out the boiled rice at breakfast; a case of jam lubricates the hard-tack; a few plugs of chewin’ are passed around to the men who are serving the guns or running telephone wire under shell fire. I wish you could all see the direct, personal comfort that your gifts are giving the American boys who are helping to show just how much there is behind what the Germans used to call the “American Bluff”. That mess fund has stepped in at a good many critical moments. Some of my memoranda of expenditures run like this: “----- bought chocolate and tobacco for the 1st. Bn. men. They had to ride from ----- to ----- in cattle cars and the stuff helped to make the journey a little less tedious.” “---- Q. M. wagon came in and we bought a good supply of grub. It served us in good stead when we were up in the mountains and the supply officer couldn’t get to us.” “---- the men would have traded their last pair of socks and thrown in a shirt for a cigarette. Hooked up with the Y.M.C.A. truck and bought them some.” “---- bought two flat-irons to help clean their uniforms.” “---- bought a big earthen crock to sterilize water in.” There are not as many of us not as there were at first. The Censor wouldn’t let me tell you about that but sometime I hope to tell you personally of Missouri boys who behaved themselves in such a way that the General of Brigade went out of his way to give them a word of praise, after it was all over. I’ll hope to tell you of the long night marches; of the men who worked in forward observation posts right up in the infantry trenches; of the couriers who carried messages day and night over shell swept roads; of the telephone linemen who got out of their blankets and mended the breaks under fire. But most of all I look forward to telling you how heart-felt is my gratitude to you all for giving me the means of helping these men keep their pep and nerve and good cheer. November 4, 1918. We are still in this quiet sector where my last letter to you was written. A great, beechnut forest with wild boar in it and quail and as two of our Texans insist – from personal encounter – wolves. We have had a great rest and have received plenty of much needed equipment. Enough action now and then to keep our attention on our jobs, but no particular danger. We see a few air battles every clear day and yesterday one of our balloons had a nervous time of it as a nervy Boche plane dodged through our anti-air craft barrage and tried to shoot it down. Our planes were too many for him though and although we did not bring him down, we chased him back to his lines. [page 3]

Description

Captain John H. Thacher of the 129th Field Artillery wrote from the front lines to his law partners in Kansas City, Missouri describing the movements of the Army in France. He describes the advancement of his troops and a German dugout that him and his men captured. Before the war, Thacher worked as an attorney with the firm Rozelle, Vineyard, Thacher, and Boys. He served on the Mexican Border and was later drafted into the Federal Army as Captain of the 129th Field Artillery. After Harry S. Truman took command of the 129th Field Artillery, Thacher was appointed adjutant of the 1st Battalion of the 129th Field Artillery , and later assumed command of the 110th Ammunition Train of the 35th Division.

Transcript

The world news comes to us fresh over the battalion radio station which is under my supervision as Adjutant. It is curious to think that the same dispatches that you are reading with your morning coffee, way off on the other side of the world, are caught by the antennae of our wireless on their way to you. We get the French, English, American and also the German “communiques”. It was fortunate today that we are so well informed. One of our officers, observer in a forward observing station, phoned in with great excitement that a whole column of Germans, wagons, men, horses, big guns and all were streaming along a road behind the German line of trenches in plain view and he begged with tears in his voice for permission to turn his battery loose on them. It was lucky – as I say – that we knew that the armistice with Austria went into effect at three o’clock this afternoon and that the troops withdrawing were Austrians. We are most luxuriously comfortable here considering that we are at the front. Good eats and warm quarters and so far – no unmentionable livestock. One of our batteries has them – poor chaps – and they are scrubbing and boiling away at every hour that Fritz gives then the opportunity. November 17, 1918. It is a brisk winter morning here, with just a suggestion of snow in the air that makes us all a bit thankful that we are not going to be in tents and bivouacs during a long Winter campaign. We have a temperamental stove of French design which gives us a Turkish bath up to the moment before it turns into a refrigerator. But with our little trips with the fourgon to the French co-operative commissaries in the neighborhood and our foraging through the various divisional Q.M.’s of this district, we make our most luxuriously. We have managed, here at battalion headquarters, to avoid the insidious “big game” of the dug-out, but some of the batteries have not been so fortunate. It is a matter that does not bear much discussion, although it is a part of dug-out life and one that the soldier regards with grim humor, just as he does most of his adversities, bless him! Already it is all becoming a bunch of memories. It is a pity that the censorship can not be relaxed somewhat, now while the [page 4]

Description

Captain John H. Thacher of the 129th Field Artillery wrote from the front lines to his law partners in Kansas City, Missouri describing the movements of the Army in France. He describes the advancement of his troops and a German dugout that him and his men captured. Before the war, Thacher worked as an attorney with the firm Rozelle, Vineyard, Thacher, and Boys. He served on the Mexican Border and was later drafted into the Federal Army as Captain of the 129th Field Artillery. After Harry S. Truman took command of the 129th Field Artillery, Thacher was appointed adjutant of the 1st Battalion of the 129th Field Artillery , and later assumed command of the 110th Ammunition Train of the 35th Division.

Transcript

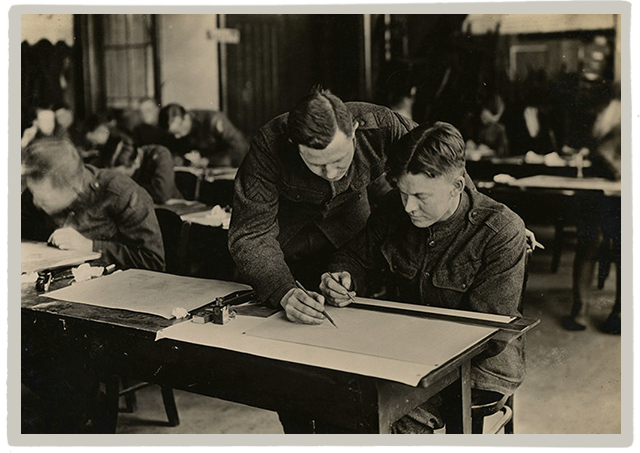

pictures are still fresh in the minds of those who created them. The incidents that really tell the story are the small ones that everybody forgets. The one general impression that we have in the Regiment is that we have been blessed with the most extraordinary good fortune though it all. Every battery commander has his story of marvelous escapes and narrow squeaks. It is undoubtedly true that a fine lot of Missouri and Kansas boys will come home and greet their wives, mothers and sweethearts, but those boys would be underneath wooden crosses in French soil of the Argonne forest if it had not been for the large proportion of German shells that were “duds”. Capt. Marks had one fall right at his side that did not go off – a big 210. One man in “D” had one strike squarely between his legs as he was sitting at the roadside our first day out on the last drive. Moreover, nobody seems to have a theory to explain why the Boche did not end the career of our little outfit that day when they had our whole big, lumbering column bracketed in the open – not once, but twice in the same day. Personally, I think that either their observing posts were poorly handled or else they were following some of their rigid schedules of harassing fire under which they put over at certain hours, a fixed number of rounds, and then quiet. Perhaps a good, old-fashioned faith in the ninety-first Psalm is the best and most appropriate basis for our escape. It’s enough for me. And again, it takes that grand old Bible song to account for our small losses during those five mortal days when our battalion was under fire in “Death Valley”. (Excuse the enlisted mens’ dramatic title.) The censorship will not permit me to tell just what happened to the outfit that took our place, but it was of such nature as to make us feel ourselves fortunate that we were relieved at the time we were. I think the picture that will stick with me the longest will be of that morning when we went into position in the valley. The night before we had slept in the princely German dug-outs. The Major and Bourke and I poured over the maps while the battery commanders and the telephone men sprawled over the floor and in the bunks and back in the cavernous tunnels in the hill. The Major and I had a kind of feeling that such big things were going to happen next day that sleep was a sort of crime, and that we ought somehow to be doing something. So by the light of the sputtering candle with a compass and a protractor we tried to forestall next morning’s events. Do you know what a French battle map is? It looks like the trail of one million drunken beetles. It has zig-zags and single lines and double lines and fuzzy lines and little moustachios and contour lines and Route National lines and “impassable” roads and lanes and “roads-partly-passable” and title lines and mills and geodetic points and church steeples and trenches and Strong Points and barbed wire and dug-outs and battery positions and the sources of springs and swamps and “Cotes” and every “Ouvrage” and “Bois” and “Ravin” and creation of the Lord or man that could mix and jumble the mind of a man trying to lead our a column of artillery into action. Especially since most of the things they record are wiped out beyond identification by shell fire and the quick changes of a few weeks‘ active warfare. Before I came into this game, a map was one of the deepest of man’s created mysteries to me. I never could follow the course of the Burlington across Missouri unles it was marked with a black line a quarter inch wide. But now, with the little preparation we had at Coetquidan, we had to get out at any moment, in the pitch darkness of a rainy, black night and feel our way forward by the help of those beetle-track “Plan Directeurs”.

Description

Captain John H. Thacher of the 129th Field Artillery wrote from the front lines to his law partners in Kansas City, Missouri describing the movements of the Army in France. He describes the advancement of his troops and a German dugout that him and his men captured. Before the war, Thacher worked as an attorney with the firm Rozelle, Vineyard, Thacher, and Boys. He served on the Mexican Border and was later drafted into the Federal Army as Captain of the 129th Field Artillery. After Harry S. Truman took command of the 129th Field Artillery, Thacher was appointed adjutant of the 1st Battalion of the 129th Field Artillery , and later assumed command of the 110th Ammunition Train of the 35th Division.

Transcript

Mont Dore, France, District Puy de Dome, near Clearmont. December 6, 1918. I admit it this time. I have been a dog to let so much water go under the mill and never a line to you. This letter is what Stevenson would call the last groan of an ulcerated conscience. Well, it’s over, over here and so soon that we almost gasp when we think of it. We were sent up to Verdun after our campaign in the Argonne, of which I last wrote to you. And by the way, as the censorship is somewhat lifted now, I am permitted to tell you something of our past wanderings. It was first at the front in the Vosges mountains, just over the divide from Kruth. Then after long hikes to the St. Mihiel drive, where we were is reserve though harnessed and limbered up four times to go in on relief in that big push. That was where we saw the big eight hour barrage a few kilos in front of us. Then more long night marches until we came up just back of the historic old town of Varennes, where Luis XVI was captured and taken back to Paris. Here we went in behind the doughboys of the 35th Division into the Argonne. It was at a little town called Charpentry and at Baulny that our battalion made its five day stand behind the hard pressed infantry. It was there we saw our most satisfactory little war service. As I wrote you in my last, we were enfiladed by machine guns and artillery – went into position and came out of it under fire and were five days wiser in Boche hardware samples, because during the entire time we were there he kept up his delicate attentions to us. The place where I had to run the phone line to the infantry trenches was Baulny. I want to go back there some day. My impression of it is that it is a winter resort of exceedingly warm climate and that most of its architectural attractions are rather pulverized. It should not be recommended to patients with low vitality or defective heart action. Then after a week’s rest in a muddy and manure-ridden little village, Seigneulles, we went out for another series of hikes to a position very near Verdun. Here we had the entire regiment in position and were in on a peach of a little scrap at the last round. Marvin’s battalion had the best of the fun this time as only one of our batteries went forward out of position. He took two of his batteries over the hill and down behind the infantry and had 36 hours bully, hot work, with some direct fire on machine gun positions. Capt. Salisbury and Capt. Allen of Independence were in it. Fired every battery of the regiment up until the last tick of the second hand at 11 o’clock on the armistice day. It was a great sight all along the front that night. Rockets, which the night before had meant “Give us the barrage” caterpillar rockets and flares and parachute stars until the whole front as far as you could see, both from Germans and American lines, we lighted up like daytime. Over at our left in Verdun streams of Tommies and Poilus and Yanks serpentined down the narrow, ruined streets to the tune of “Over There”. The Regimental band serenaded us and every Poilu became decently drunk on good vin rouge. Since then we have marked time, fought cooties and scanned every paper for news as to homebound transports. Everybody says frankly he is ready for home and yet in further discussion there creeps in, “Well, I just wish I’d had one more crack at Fritz. Direct fire, or perhaps, with good adjustment from a forward O.P.” or “Durn it, I wish we’d had a chance to shoot up some of their towns!” And as for yours faithfully, he, too, would without any blood-thirstyness, have loved to get the gun crew of that German 77 that killed his fine old bay riding horse! Well, I’ve had a good big swig of the war game and had about all the good luck that is coming to me. Have been at various times Summery Court Officer, five months commander of a battery, three months in command of a battalion and for a week in command of the regiment and in the rest of the time and most of the time over here on my much loved job of battalion and adjutant. Just now I am down here at this “leave area” – a beautiful little French summer watering place up in the mountains, with 1200 men from two artillery brigades who have been sent down for their 7 days leave. They were a spirited bunch to handle on the long four day trip down here, crowded in box cars, 59 to a car. But now they are having the time of their lives with free table d’hote dinners, clean beds and clean sheets in hotels, baths, movies, vaudeville and all. Will rejoin the regiment next week. Best regards. [page 6]

Description

Captain John H. Thacher of the 129th Field Artillery wrote from the front lines to his law partners in Kansas City, Missouri describing the movements of the Army in France. He describes the advancement of his troops and a German dugout that him and his men captured. Before the war, Thacher worked as an attorney with the firm Rozelle, Vineyard, Thacher, and Boys. He served on the Mexican Border and was later drafted into the Federal Army as Captain of the 129th Field Artillery. After Harry S. Truman took command of the 129th Field Artillery, Thacher was appointed adjutant of the 1st Battalion of the 129th Field Artillery , and later assumed command of the 110th Ammunition Train of the 35th Division.

Transcript

The big bunch of horses that came in today and the Chauchat rifles issued to the batteries look ominously as though we were going over to “occupy” with the Army of Occupation. A nice winter residence, perhaps, in some salubrious, north Europe spot where fuel is as scares as supplies! Hurroo! Well, I’m in this thing to see it through and I can learn to say in German my pathetic speech about my Major’s long work and fatigue and illness etc. that used to get “oeufs” and “Vin Blanc” along our marches in France. Ich bin, du bist, er ist, wir sind, ihr seid, sie sind, etc. Bring on Russia and the Dardenelles and Siberia and all the others. “We’re here to stick”, as the Battalion said to the Infantry when we were under fire at Charpentry. The Stars come, fine and reg’lar and are enjoyed by all. Do not waste any sympathy on us for our Christmas next week on the line. We have the promise of twenty-four mellifluous-voiced and versatile “cullud” brethern from the negro regiment of engineers near us for a Christmas Eve celebration. We are going to have a real Christmas tree of our own and I have a copy of the Christmas Carol just received from Mary and we will brew a “fire-tong bowl” like we used to have at the Christmas Pantomimes and we will try to make a cheerful little day of it – rain, rats, cooties, to the contrary notwithstanding.

Description

Captain John H. Thacher of the 129th Field Artillery wrote from the front lines to his law partners in Kansas City, Missouri describing the movements of the Army in France. He describes the advancement of his troops and a German dugout that him and his men captured. Before the war, Thacher worked as an attorney with the firm Rozelle, Vineyard, Thacher, and Boys. He served on the Mexican Border and was later drafted into the Federal Army as Captain of the 129th Field Artillery. After Harry S. Truman took command of the 129th Field Artillery, Thacher was appointed adjutant of the 1st Battalion of the 129th Field Artillery , and later assumed command of the 110th Ammunition Train of the 35th Division.

Details

| Title | John H. Thacher letters to Pards - October 7, 1918 - December 6, 1918 |

| Creator | Thacher, John H. |

| Source | Thacher, John H. Letters to Pards. 07 October 1918 - 06 December 1918. John H. Thacher Papers. Harry S. Truman Library and Museum, Independence, Missouri. |

| Description | Captain John H. Thacher of the 129th Field Artillery wrote from the front lines to his law partners in Kansas City, Missouri describing the movements of the Army in France. He describes the advancement of his troops and a German dugout that him and his men captured. Before the war, Thacher worked as an attorney with the firm Rozelle, Vineyard, Thacher, and Boys. He served on the Mexican Border and was later drafted into the Federal Army as Captain of the 129th Field Artillery. After Harry S. Truman took command of the 129th Field Artillery, Thacher was appointed adjutant of the 1st Battalion of the 129th Field Artillery , and later assumed command of the 110th Ammunition Train of the 35th Division. |

| Contributing Institution | Harry S. Truman Library and Museum |

| Rights | Documents in this file are in the public domain. |

| Date Original | 1918 |

| Language | English |