John H. Thacher letters to Pards - October 12, 1918 - December 22, 1918

Transcript

October 12, 1918. The Q.M. wagon has just rolled in and has taken up some of the capital you invested. So I will drop you all a line or two to let you know where the kindly touch of your halpful donations is being felt. We are just in from the front. We are hove up in billets to rest and sleep and get new clothes and horses and blankets and canteens and mess-kits and such stuff to make up for what we have distributed over the landscape of France in our last campaign. Our men have been twice at the front and have all of them had a good stiff drink of the Game of War. I think that it’s the “morning-after” sensation we are suffering from now. Part of our bunch went into position under shell fire on the last drive and were under fire from flanking Boche batteries for some five days. We were up with the infantry second lines. As one of the boys expressed it: “We couldn’t have been any forwarder without charging the Boche with our limbers!” At such times roads are blocked; supply trains delayed; columns are caught under artillery fire and the ration wagons somehow don’t get up. Grub runs low and worst of all, tobacco gives out. It’s then that the good friends from the little village on the Missouri and Kaw step into the breach. A carton of precious cigarettes is dragged out from its hiding place in a fourgon; some canned milk helps out the boiled rice at breakfast; a case of jam lubricates the hard-tack; a few plugs of chewin’ are passed around to the men who are serving the guns or running telephone wire under shell fire. I wish you could all see the direct, personal confort that your gifts are giving to the American boys who are helping to show just how much there is behind what the Germans used to call the “American Bluff”. That means fund has stepped in at a good many critical moments. Some of my memoranda of expenditures run like this: “----- bought chocolate and tobacco for the 1st. Bn. men. They had to ride from ----- to ----- in cattle cars and the stuff helped to make the journey a little less tedious.” “---- Q.M. wagon came in and we bought a good supply of grub. It served us in good stead when we were up in the mountains and the supply officer couldn’t get to us.” “---- the men would have traded their last pair of socks and thrown in a shirt for a cigarette. Hooked up with a Y.M.C.A. truck and bought them some.” “---- bought two flat-irons to help clean up their uniforms.” “---- bough a big earthen crock to sterilize water in.” There are not as many of us now as there were at first. The Censor wouldn’t let me tell you about that but sometime I hope to tell you personally of Missouri boys who behaved themselves in such a way that the General of the Brigade went out of his way to give them a word of praise, after it was all over. I’ll hope to tell you of the long night marches; of the men who worked in forward observation posts right up in the infantry trenches; of the couriers who carried messages day and night over shell swept roads; of the telephone linemen who got out of their blankets and mended the breaks under fire. But most of all I look forward to telling you how heart-felt is my gratitude to you all for giving me the means of helping these men keep their pep and nerve and good cheer. November 4, 1918. We are still in this quiet sector where my last letter to you was written. A great, beechnut forest with wild boar in it and quail and as two of our Texans insist – from personal encounter – wolves. We have had a great rest and have received plenty of much needed equipment. Enough action now and then to keep our attention on our jobs, but no particular danger. We see a few air battles every clear day and yesterday one of our baloons had a nervous time of it as a nervy Boche plane dodged through our anti-air craft barrage and tried to shoot it down. Our planes were too many for him though and although we did not bring him down, we chased him back to his lines.

Description

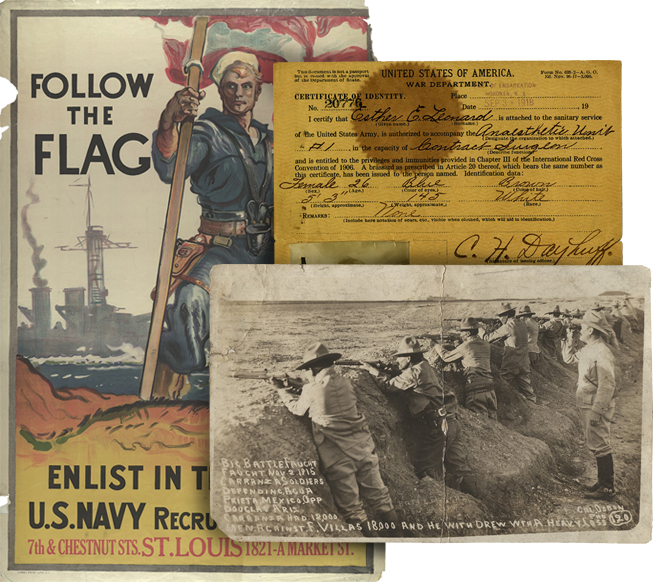

Captain John H. Thacher of the 129th Field Artillery writes to his law partners in Kansas City, Missouri describing life in the Army before and after the armistice. Before the war, Thacher worked as an attorney with the firm Rozelle, Vineyard, Thacher, and Boys. He served on the Mexican Border and was later drafted into the Federal Army as Captain of the 129th Field Artillery. After Harry S. Truman took command of the 129th Field Artillery, Thacher was appointed adjutant of the 1st Battalion of the 129th Field Artillery , and later assumed command of the 110th Ammunition Train of the 35th Division.

Transcript

A boy from one of the doughboy regiments who is a laison runner has just been talking with me and had an interesting souvenir of the fight we were last ine. He was one of the infantry scouts sent forward in front of the advancing lines to draw the enemy’s fire and thus locate the machine guns. It was of course a ticklish job for a youngster lately from a farm near St. Joseph, Missouri. He worked his way forward, dodging from one shell hole to another, and finally when the boche shell fire became too heavy he ducked into a crater to wait a bit until things quieted down. He was astonished as he lay there to have a moist, friendly muzzle shoved over the rim of the crater – not the muzzle of a Boche rifle, but of a Boche dog. The creature wagged his tail in a friendly way and then crawled down into the pit with the soldier. He would lie flat as your hat when he heard a shell whistling, and after it burst he would jump up on the alert to see what had happened and where it had burst. It was one of the German “Dienst-Hunds” or service dogs. They are sent out with messages and occasionally with supplies for the wounded. He was thoroughly familiar with shell fire and knew just where to go and how to behave when it was in the air. He made friends with my man and stayed with him until he was finally through with his mission and started back to the rear. He refused to go in that direction and no coaxing or blandishments could take him away from the German lines. The soldier, before he left, took off his dog collar and chain. It was all carefully numbered with his division and sector and branch of the service and a word that showed that he had been given the “Mylene Test”, a medical inoculation given to horses and animals. The heavy metal of the collar, the thoroughness of the system by which even that dog had been inoculated, tested, numbered, registered, trained and put into his groove in the great German war machine, was almost terrifying. The world news comes to us fresh over the battalion radio station which is under my supervision as Adjutant. It is curious to think that the same dispatches that you are reading with your morning coffee, way off on the other side of the world, are caught by the antennae of our wireless on their way to you. We get the French, English, American and also the German “communiques”. It was fortunate today that we are so well informed. One of our officers, observer in a forward observing station, phoned in with great excitement that a whole column of Germans, wagons, men, horses, big guns and all were streaming along a road behind the German line of trenches in plain view and he begged with tears in his voice for permission to turn his battery loose on them. It was lucky – as I say – that we knew that the armistice with Austria went into effect at three o’clock this afternoon and that the troops withdrawing were Austrians. We are most luxuriously comfortable here considering that we are at the front. Good eats and warm quarters and so far – no unmentionable livestock. One of our batteries has them – poor chaps – and they are scrubbing and boiling away at every hour that Fritz gives them the opportunity. November 17, 1918. It is a brisk winter morning here, with just a suggestion of snow in the air that makes us all a bit thankful that we are not going to be in tents and bivouacs during a long Winter campaign. We have a temperamental stove of French design which gives us a Turkish bath up to the moment before it turns into a refrigerator. But with our little trips with the fourgon to the French co-operative commissaries in the neighborhood and our foraging through the various divisional Q.M.’s of this district, we make out most luxuriously. We have managed, here at battalion headquarters, to avoid the insidious “big game” of the dugout, but some of the batteries have not been so fortunate. It is a matter that does not bear much discussion, although it is a part of dug-out life and one that the soldier regards with grim humor, just as he does most of his adversities, bless him! Already it is all becoming a bunch of memories. It is a pity that the censorship can not be relaxed somewhat, now while the

Description

Captain John H. Thacher of the 129th Field Artillery writes to his law partners in Kansas City, Missouri describing life in the Army before and after the armistice. Before the war, Thacher worked as an attorney with the firm Rozelle, Vineyard, Thacher, and Boys. He served on the Mexican Border and was later drafted into the Federal Army as Captain of the 129th Field Artillery. After Harry S. Truman took command of the 129th Field Artillery, Thacher was appointed adjutant of the 1st Battalion of the 129th Field Artillery , and later assumed command of the 110th Ammunition Train of the 35th Division.

Transcript

pictures are still so fresh in the minds of those who created them. The incidents that really tell the story are the small ones that everybody forgets. The one general impression that we have in the Regiment is that we have been blessed with the most extraordinary good fortune through it all. Every battery commander has his story of marvelous escapes and narrow squeaks. It is undoubtedly true that a fine lot of Missouri and Kansas boys will come home and greet their wives, mothers and sweethearts, but those boys would be underneath wooden crosses in French soil of the Argonne forest if it had not been for the large proportion of German sheels that were “duds”. Capt. Marks had one fall right at his side that did not go off – a big 210. One man in “D” had one strike squarely between his legs as he was sitting at the roadside our first day out on the last drive. Moreover, nobody seems to have a theory to explain why the Boche did not end the career of our little outfit that day when they had our whole big, lumbering column bracketed in the open – not once, but twice in the same day. Personally, I think that either their observing posts were poorly handled or else they were following some of their rigid schedules of harassing fire under which they put over at certain hours, a fixed number of rounds, and then quit. Perhaps a good, old-fashioned faith in the ninety-first Psalm is the best and most appropriate basis for our escape. It’s enough for me. And again, it takes that grand old Bible song to account for our small losses during those five mortal days when our battalion was under fire in “Death Valley”. (Excuse the enlisted mens’ dramatic title.) The censorship will not permit me to tell just what happened to the outfit that took our place, but it was of such nature as to make us feel ourselves fortunate that we were relieved at the time we were. I think the picture that will stick with me the longest will be of that morning when we went into position in the valley. The night before we had slept in the princely German dugouts. The Major and Bourke and I poured over the maps while the battery commanders and the telephone men sprawled over the floor and in the bunks and back in the cavernous tunnels in the hill. The Major and I had a kind of feeling that such big things were going to happen next day that sleep was a sort of crime, and that we ought somehow to be doing something. So by the light of a sputtering candle with a compass and a protractor we tried to forestall next morning’s events. Do you know what a French battle map is? It looks like the trail of one million drunken beetles. It has zig-zags and single lines and double lines and fuzzy lines and little moustachios and contour lines and Route National lines and “impassable” roads and lanes and “roads-partly-passable” and title lines and mills and geodetic points and church steeples and trenches and strong Points and barbed wire and dug-outs and battery positions and the sources of springs and swamps and “Cotes” and every “Ouvrage” and “Bois” and “Ravin” and creation of the Lord or man that could mix and jumble the mind of a man trying to lead out a column of artillery into action. Especially since most of the things they record are wiped out beyond identification by shell fire and the quick changes of a few weeks’ active warfare. Before I came into this game, a map was one of the deepest of man’s created mysteries to me. I never could follow the course of the Burlington across Missouri unles it was marked with a black line a quarter inch wide. But now, with the little preparation we had at Coetquidan, we had to get out at any moment, in the pitch darkness of a rainy, black night and feel our way forward by the help of those beetle-track “Plan Directeurs”.

Description

Captain John H. Thacher of the 129th Field Artillery writes to his law partners in Kansas City, Missouri describing life in the Army before and after the armistice. Before the war, Thacher worked as an attorney with the firm Rozelle, Vineyard, Thacher, and Boys. He served on the Mexican Border and was later drafted into the Federal Army as Captain of the 129th Field Artillery. After Harry S. Truman took command of the 129th Field Artillery, Thacher was appointed adjutant of the 1st Battalion of the 129th Field Artillery , and later assumed command of the 110th Ammunition Train of the 35th Division.

Transcript

December 10, 1918. I am sitting in a gem of a little café with old paintings and Roman bas reliefs around me and the “Pratron” bowing and scraping as he shows me his genuine Murillos and his coins and relics of the time of that gentleman who invented the Latin subjunctive and indirect discourse, “Vercingetorix”; the only old Gaul who licked one J. Caesar several years ago and to whom there is a monument in the square here. A tall bottle of Chateau la Faitte occupies the right sector of my tactical position. I am threatened on my left by “Poulet” (unknown in the mud and cootie-ridden regions of Verdun), and my immediate front is menaced by a frontal attack of “Potage”, “Canard”, and “Patisserie et Framage”. It is indeed a critical situation calling for all that the Field Regulations and the Drill Regulations of F.A. and the maxims of Napoleon have to offer. All of which, being simplified, means that I have been sent down as Commandant of a section of 1200 “permissionaires” – 7 day furlough men – who are enjoying Uncle Sam’s hospitality for a week at a choice French summer resort and former Monte Carlo in the Auvergne Mountains, where they have clean beds and six course table d’hote dinners and movies and hot baths, all free for one blissful week, before they are returned to dug-outs and cooties and “canned Willie”. I am Police Commissioner and censor and Father Confessor to 1200 lively Americans and, if I survive, I will rejoin my regiment and receive membership in the Acadamie Francaise with the Croix de Guerre and the Cordon d’Honneur and all the rest – including the Congressional medal. The five days under fire in the Argonne and the service at St. Mihiel, Verdun and the rest are as nothing to this. Verdun, December 22nd, 1918. When I returned from my anxious wanderings with my 1200 ducklings at Mont Dore, I found a wonderful batch of mail awaiting me. It was a great treat and made up for all the sleepless nights I had spent on the journey. I enclose herewith a little testimonial from the Commander of the leave area in reference to my stewardship of my flock on the recent trip. He said he had never given one like it to any other officer. If my children were considered so angelic I wonder what the rest of them were like! I also got statements from the Y.M.C.A. officials and the Railroad Transportation officer to similar effect. So I will have some retort ready when the French begin to put in claims for damage to their rolling stock and freight cars along the route. The trip took four days and four nights both ways and was a pretty exhausting experience for the Commanding Officer. We will have a Christmas Eve minstrel performance with the aid of some colored talent from the Engineer Corps over at Verdun. We are receiving horses and mules now, and this may mean that we are going to make a hike over into Germany, but nobody knows. Out regiment was in the final advance that was made towards Etain here in front of us, but we were not up at Sedan as some of your letters from home seem to have placed us. Our big party was in the Argonne Forest where we were under fire and had such a lively time for five days at Charpentry and Baulny. Have you found those two little towns on the map? They are just north of Varennes where Louis XVI was captured on his flight from Paris. We shall always remember Charpentry and Baulny. At the latter town our infantry of the 35th Division were being mauled and enfiladed by cross-fire from machine guns and artillery and our little battalion stood behind them in their second line trenches and supported them when they needed it most. It was the real artillery stuff. Just the thing we had lived for and dreamed about. Shells whistling over while out little Miss Swazant Kanze talked back most saucily. And when I had the chance to take our artillery wire forward up into the infantry trenches to establish the forward O.P. I had the greatest picture of the real battle scene that one could hope to see in a whole war. Machine guns with white puffs along the edge of the woods and barrages falling just in front of them and men firing from the trenches and all that. Only I wish the blamed Boche hadn’t cut my wire with their 77’s so that I could have had a some fun adjusting on the beggars all by my lonesome. Well, that’s all history now, and here I be, maundering about it already.

Description

Captain John H. Thacher of the 129th Field Artillery writes to his law partners in Kansas City, Missouri describing life in the Army before and after the armistice. Before the war, Thacher worked as an attorney with the firm Rozelle, Vineyard, Thacher, and Boys. He served on the Mexican Border and was later drafted into the Federal Army as Captain of the 129th Field Artillery. After Harry S. Truman took command of the 129th Field Artillery, Thacher was appointed adjutant of the 1st Battalion of the 129th Field Artillery , and later assumed command of the 110th Ammunition Train of the 35th Division.

Transcript

Verdun, December 18, 1918 Just back from the trip to the leave area. Maybe you think it was not a job to keep those husky young American under control. Feel pretty nearly ready for a leave myself. But I bore away from Mont Dore, the town we invaded, a statement from the commanding officer of the district that our cherubs had behaved most angelically and that my services were satisfactory; but I shall probably be stuck “beaucoup frances” – a pay check or two – when the reports come in from along the line of various freight cars into which inquisitive and acquisitive hands from our train were deftly inserted when the Military Police were on the other side of the car. How I dreaded the lights or switches that showed we were coming into a town with fresh temptations to 600 wild mavericks. But what I really started to write about was the wonderful batch of letters that I found awaiting me when I returned – a whole stack of them that made the Major and Bourke wild with envy, each offering his servies, however, as secretary and censor. Lordy! Lordy! What a treat! Everything! News clippings, three copies of a sweet little document, “Hershey’s Milk Chocolate”, all fresh and delicious. Then letters from absolutely everybody. It was a most rascally conspiracy – and I’m for it strong! I am ashamed of the perfunctory marginal foot note I put on my last letter referring to the “excerpts”. It must have meant a heap of labor and planning and just durned patient hard work to have fixed up those copies you sent out and the scheme has given one member of the A.E.F. a whole lot of pure unadulterated joy. I used to say that there were three occasions in life that made human nature unfold and soften and exhibit its generous side: Christmas, a funeral and a wedding. Now I add one more – a war! Well, thanks now, a heap from the heart out! Those letters made a great homecoming for me when I got back to my shack in the desolate shell-raked woods of Verdun. The big bunch of horses that came in today and the Chauchat rifles issued to the batteries look ominously as though we were going over to “occupy” with the Army of Occupation. A nice winter resident, perhaps, in some salubrious, north Europe spot where fuel is as scarce as supplies! Hurroo! Well, I’m in this thing to see it through and I can learn to say in German my pathetic speech about my major’s long work and fatigue and illness etc. that used to get “oeufs” and “Vin Blanc” along our marches in France. Ich bin, du bist, er ist, wir sind, ihr seid, sie sind, etc. Bring on Russia and the Dardenelles and Siberia and all the others. “We’re here to stick”, as the Battalion said to the Infantry when we were under fire at Charpentry. The Stars come, fine and reg’lar and are enjoyed by all. Do not waste any sympathy on us for our Christmas next week on the line. We have the promise of twenty-four mellifluous-voiced and versatile “cullud” brethren from the negro regiment of engineers near us for a Christmas Eve celebration. We are going to have a real Christmas tree of our own and I have a copy of the Christmas Carol just received from Mary and we will brew a “fire-tong bowl” like we used to have at the Christmas Pantomimes and we will try to make a cheerful little day of it – rain, rats, cooties to the contrary notwithstanding.

Description

Captain John H. Thacher of the 129th Field Artillery writes to his law partners in Kansas City, Missouri describing life in the Army before and after the armistice. Before the war, Thacher worked as an attorney with the firm Rozelle, Vineyard, Thacher, and Boys. He served on the Mexican Border and was later drafted into the Federal Army as Captain of the 129th Field Artillery. After Harry S. Truman took command of the 129th Field Artillery, Thacher was appointed adjutant of the 1st Battalion of the 129th Field Artillery , and later assumed command of the 110th Ammunition Train of the 35th Division.

Transcript

Speaking of cooties, I must tell you one of the trip that was delicious as a typical soldier stunt. When our men had had their long four day trip down to the leave area and were lined up just ready to go to the promised land – good beds, clean rooms, table d’hotes, hot baths and all, a Gorgon suddenly stood in their path with medical insignia on his collar and went down the line demanding, before they went into those clean beds and those Elysian fields, to know who had cooties. Horrors! Visions of a fat fading Paradise. At the very gates and then cast out because of an innocent entymological collection. Oh!no. Nobody had them! All had been “de-loused” before leaving as required by brigade orders. There were only some fifty odd out of twelve hundred that confessed ownership. These were ordered to report for baths and clean underclothes before they used the beds. When the crowds poured into the Roman baths and say the great piles of attractive clean underwear and clean warm wool socks and clean shirts, their own travel-worn outfits were suddenly uncomfortable. They crowded up to get the new stuff. “Oh no! said the medico-Gorgon, “these are only for men with cooties.” Oh that was it, was it? Divers of the crowd disappeared. There were consultations, market quotations, bartering and trading. Then divers and sundry ones trooped back. “We’ve got cooties”, they shyly admitted. “Show ‘em”, said the doctor. Up came hems of undershirts. Sure enough, there they were – lively and educated. The new underclothes were issued. Instead of fifty there were some two hundred who had ‘em. But what the ruling price of cooties mounted to that day, I will never tell. It is a military secret. (Postal card from Menton. 1/27/[1919]) now storming Italy on leave. Am looking out over the Mediterranean with a large bottle of Italian Capri wine in front of me. It’s a terrible War.

Description

Captain John H. Thacher of the 129th Field Artillery writes to his law partners in Kansas City, Missouri describing life in the Army before and after the armistice. Before the war, Thacher worked as an attorney with the firm Rozelle, Vineyard, Thacher, and Boys. He served on the Mexican Border and was later drafted into the Federal Army as Captain of the 129th Field Artillery. After Harry S. Truman took command of the 129th Field Artillery, Thacher was appointed adjutant of the 1st Battalion of the 129th Field Artillery , and later assumed command of the 110th Ammunition Train of the 35th Division.

Details

| Title | John H. Thacher letters to Pards - October 12, 1918 - December 22, 1918 |

| Creator | Thacher, John H. |

| Source | Thacher, John H. Letters to Pards. October 12, 1918 - December 22, 1918. John H. Thacher Papers. Harry S. Truman Library and Museum, Independence, Missouri. |

| Description | Captain John H. Thacher of the 129th Field Artillery writes to his law partners in Kansas City, Missouri describing life in the Army before and after the armistice. Before the war, Thacher worked as an attorney with the firm Rozelle, Vineyard, Thacher, and Boys. He served on the Mexican Border and was later drafted into the Federal Army as Captain of the 129th Field Artillery. After Harry S. Truman took command of the 129th Field Artillery, Thacher was appointed adjutant of the 1st Battalion of the 129th Field Artillery , and later assumed command of the 110th Ammunition Train of the 35th Division. |

| Contributing Institution | Harry S. Truman Library and Museum |

| Rights | Documents in this file are in the public domain. |

| Date Original | 1918 |

| Language | English |