Ward Loren Schrantz Memoir - 1917-1919

Transcript

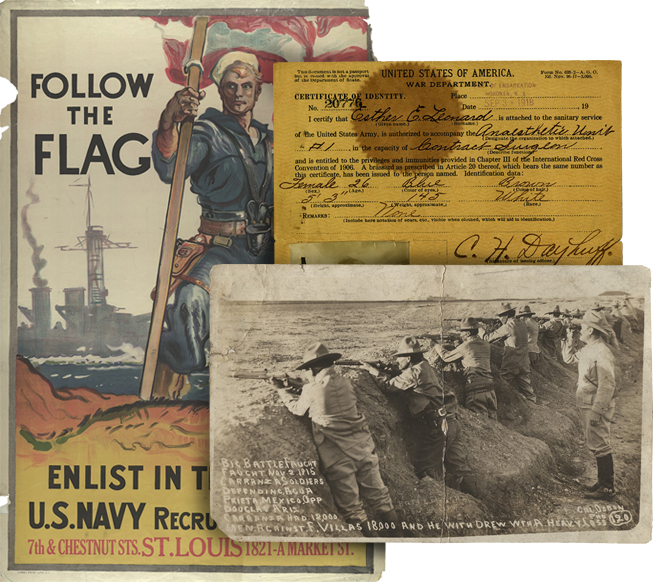

The Accurate Line

Transcript

From Mrs. W.L. Schrantz 125 W. Centennial Ave. Carthage [Missouri] 64836 To Mrs. R.E. Truman 5446 Harrison St., Kansas City, [Missouri] 64110

Transcript

[sticker]

Transcript

City of Carthage Memorial Hall Board Carthage, Missouri

Transcript

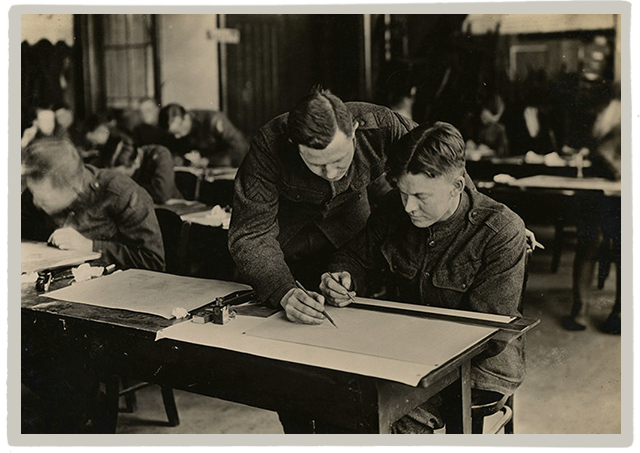

[photograph] The above picture was taken at Camp Clark, Nevada, in the summer of 1909. Front row, left to right: Clark O'Donnell, Clyde Greeson, Fred McQuivey, Unidentified (possibly William Fasken,) Ora Fees, Lew D. Perry, Guy A. Roos, Floyd R. Hirst, Harry M. Bouser, Lee Landers, Carl (Poke) Hampton, Louis E. Dettwiler, Arthur C. Burke, Henry Pipkin, John H. (Ham) Bates, Unidentified, Capt. W.E. Hiatt. Second row, Second Lieut. Roy C. Thompson, Urban Tuttle, Milton Wash, unidentified, Fred Bennett, unidentified, James Galbraith, Ward Schrantz, unidentified (possibly Carl Murdock,) Dwight Murto, Clyde Narramore, James Bogardus, James Mealey, Schell Mitchell (cook,) Stanley Saylor, Fred Mitchell (cook,) Fred Jennison. Co A, 2d Infantry, Missouri National Guard

Transcript

Nature, kindly or otherwise, endowed me with an innate interest in military subjects and in military history and my boyhood in Carthage, [Missouri] was filled with thoughts along that line. Veterans of the great civil war were all about in my home town at that time and many of them willing enough to tell their experiences to an interested small boy. This, together with the outbreak of the Spanish-American war in the spring of 1898, with the epidemic of wars various places in the world the next six years, all liberally treated in newspapers and magazines, fostered and encouraged the natural inclination. Campaigns in Cuba and in the Philippines; the Boxer rebellion, the Boer war, and the Russian-Japanese war, all were subjects of boyhood conversations and games. These things naturally influenced mental trends and most of the small boys with whom I "played war," eventually served in the national guard, army or marines in the next 15 years even before our entry into the first world war put so many men in uniform. As a boy between seven and eight years old I saw the local national guard company -- the Carthage Light Guard -- march away as Company A, Second Missouri Volunteer Infantry, to the railway station to entrain for Jefferson Barracks. They appeared huge men to me, a small boy, as I stood in the muddy street watching them -- blue uniformed, their long 1872-model caliber 45 Springfield rifles, sloped off their shoulders at what seemed neat angles to me but probably were not; their knapsacks on their backs with the blankets in a small roll transversely across the top. In memory, looking

Transcript

[page 2] back at them, they still seem huge -- viewing them as I still do mentally from the altitude of a seven-year-old boy. I did not know then -- or I would have been happier at being too small for the war -- that years later I would march in the same company and from the same armory as a sergeant away myself/ to the Mexican border troubles, or that I would again march away with it as its captain at the beginning of the first world war and would command it when it first went into battle. I became well acquainted with Col. W.K. Caffee, then the commander of that volunteer regiment, and of Capt. John A. McMillan, then Company commander, and heard from their own lips the story of the regiment's activities and trials in the months that followed. It was an old unit, as Missouri national guard organization went, having been formed in 1876 under the influence of Col. Caffee, then one of the gilded youth of the town and fresh from Shattuck, military school, but with its first officers and a nucleus of its rank and file veterans of the great Civil War, some of the Confederate army, some of the Federal. And as commander of the company in later years I took pride in the fact that within 11 years after the Civil War closed, in this town of southwest Missouri which the hostilities had reduced to ashes and around which the border war was most bitter, veterans of opposing armies could get together in the same military organization. And still as a seven-year-old boy I watched a second volunteer unit -- Co. G, 5th Missouri Volunteer Infantry -- march away, unarmed and in civilian clothes, for the train to Jefferson Barracks. I was to hear much of Capt. George P. Whitsett, its commander,

Transcript

[page 3] later. After his company was mustered out he gained publicity in connection with some proposed filbustering expedition to Nicaragua, nipped in the bud by our own government but for which he had signed up a number of his volunteer soldiers. Then he became an officer in the 34th (?) U.S. Volunteer Infantry in the Philippines and wrote letters to the home newspapers about fighting in northern Luzon. Still later he was connected with the constabulary there and was some kind of a judge in the administration of the island. Newspaper readers in these days heard much of the "water-cure," a form of torture said to have been inflicted on suspected native guerrillas in the Philippines to make them confess their offenses, and in my imagination I connected him -- and probably quite unjustly -- with those. In World War I, I knew him as the judge advocate of the 35th Infantry division and later of a corps staff and cited for gallantry in action. At the time of his death some years after that war he was a major in the regular army. My early military interests had a rather adverse and now amusing influence on my high school career. Naturally interested in history I narrowly avoided flunking out in that subject due to my inclinations to dig into reference books containing more details of military movements than the textbooks possessed. Hence of the allotted pages I knew relatively little and was in consequent disgrace, quite humiliating at the time. But despite it I have since always congratulated myself on my tangent directed energy and poor scholarship in this regard. A less laudable high school fault my senior year was an interest in the writings of Karl Marx which did not influence me very long but which ran somewhat counter to my natural trend. But even that probably has its value since in my vigorous spasm of reading I

Transcript

[page 4] acquired a good deal of knowledge of communist doctrines which have in later years given me a certain foundation on which to argue against them, and at the same time helped toward an understanding of the stuff out of which the formidable Red army of the second world war was built. However my military inclinations soon won over my early Socialist leanings and three months after I was 18 I enlisted in the national guard, and organization which was anathema to my erstwhile Socialist associates who had picked me as a promising young radical becoming instead one of those young men opprobriously referred to as "scab-herders" by my late associates. I always have remembered with a smile a comment one of my elderly Socialist friends made to me a short time later. "Ward" he said sadly, "I always thought you were a pretty good boy -- until, concluding with energy, "you went and joined the damn milishy." And another one said to me not long afterwards when he dropped into the newspaper office where I was employed: "Ward, if you were on duty with the militia and you were ordered to fire on a crowd and your brother was right in front of you, would you shoot your brother?" "Of course," I replied brazenly to shock him, "that is exactly what he would do to me if the situation were reversed." He had no answer to that, but it was a reply I could make easily since both of my two older brothers were and are violently loyalist and strong law-and-order men and if they ever have had any inclinations to shoot me it probably was during that brief period when I was reading Karl Marx and Frederick Engels.

Transcript

[page 5] On the evening of [February] 5, 1909, I went to the local national guard armory, asked rather timidly how one went about enlisting, and was ushered promptly to the company office where I was put through a form of physical examination by Capt. W.E. Hiatt, the company commander, and sworn in forthwith, my physical examination by a civilian physician following afew days later. Capt. Hiatt was a national guardsmen of some 15 years or so service and had been a second lieutenant in the volunteer unit during the Spanish war. He was a courteous gentlemen and able soldier and I liked him as well as any officer, regular or national guard, under whom I later served. I was issued immediately a tight-fitting blue uniform with bright buttons, a bell-topped cap with cross-rifles on the front and a 1903 Springfield rifle with bayonet -- the clothing to be taken home and the rifle and bayonet kept in the arms rack. I did not do so well a short time later when I drew khaki. There was a blouse with bright buttons, a pair of straight trousers, and leggins large enough for a man with twice my caliber of legs so that the first practice march I took they were bagging down around my ankles. Shirts were not then an article of issue in the Missouri National Guard and each man bough his own of blue chambray. The straight trousers, I learned, were already obsolete - the regular army wearing khaki breeches. About 30 years later, after a great deal of wandering around with other types, the army came back to trousers and leggins not unlike those then out of style. The hat issued was the high crowned campaign hat, creased in the center, and with blue hat cord.

Transcript

[page 6] This organization -- Company A Second Missouri, Infantry officially, and still the Carthage Light Guard locally - was in the doldrums though I learned later it was still one of the best units in the regiment. The high social status it had once enjoyed had been lost back in the late 'nineties though something of the old reputations of a crack militia outfit still lingered. There was no pay attached and attendance at drill was more or less voluntary. A small nucleus of enthusiasts inspired more or less by the example of the captain worked hard and drilled faithfully every Friday night while the rest dropped in when convenient or a date with the girl friend did not interfere. According to my count there were usually 20 or 25 there at that time. However some time later seeing some drill reports I noted that according to them we always had between 35 and 40. There were 58 on the muster rolls but of those a number had been away from town for a year or two, I learned. I have said the captain was an excellent officer and he was, but then as now there was sometimes a difference between being an excellent officer and being a successful national guard company commander in dull periods. The professionally skilled captain did not always have the best turn-outs. But Capt. Hiatt kept the unit going and trained his faithfuls for noncommissioned officers, and so even in this low period a volunteer unit could have been formed quickly if war came. After I had belonged to the unit for about a month there was the annual federal inspection. To pass this it was necessary actually have 35 or 40 men on the floor. This was done by getting "substitutes" from ex-members who came down for the occasion, donned a vacant uniform and answered to an absentee's name. Men stood at right shoulder arms until their names were called, then came down to the order.

Transcript

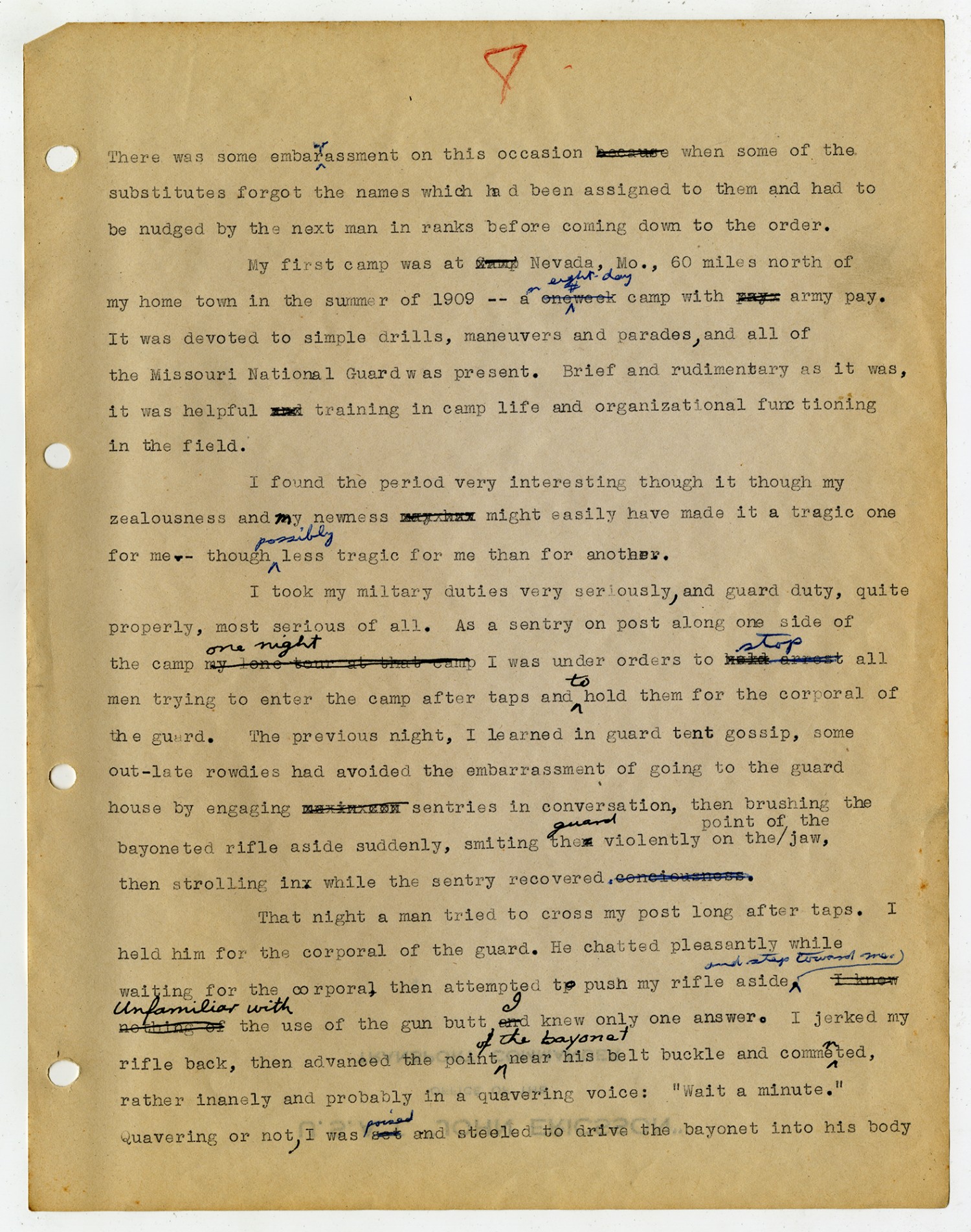

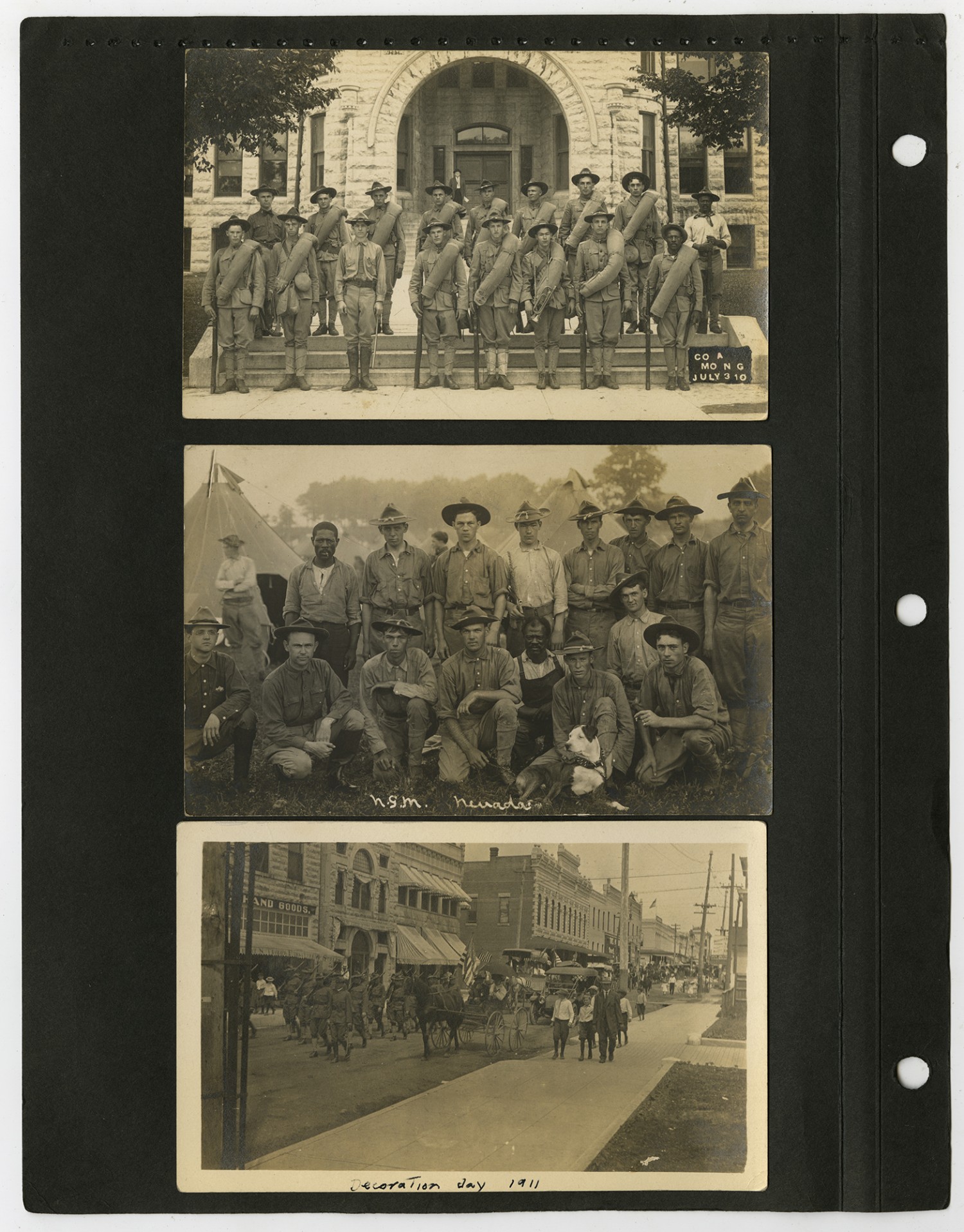

[page 7] There was some embarrassment on this occasion when some of the substitutes forgot the names which had been assigned to them and had to be nudged by the next man in ranks before coming down to the order. My first camp was at Nevada, [Missouri], 60 miles north of my home town in the summer of 1909 -- an eight day camp with army pay. It was devoted to simple drills, maneuvers and parades, and all of the Missouri National Guard was present. Brief and rudimentary as it was, it was helpful training in camp life and organizational functioning in the field. I found the period very interesting though it though my zealousness and my newness might easily have made it a tragic one for me -- though possibly less tragic for me than for another. I took my military duties very seriously, and guard duty, quite properly, most serious of all. As a sentry on post along one side of the camp one night I was under orders to stop all men trying to enter the camp after taps and to hold them for the corporal of the guard. The previous night, I learned in guard tent gossip, some out-late rowdies had avoided the embarrassment of going to the guard house by engaging sentries in conversation, then brushing the bayoneted rifle aside suddenly, smiting the guard violently on the point of the jaw, then strolling in while the sentry recovered. That night a man tried to cross my post long after taps I held him for the corporal of the guard. He chatted pleasantly while waiting for the corporal then attempted to push my rifle aside and step toward me. Unfamiliar with the use of the gun butt, I knew only one answer. I jerked my rifle back, then advanced the point of the bayonet near his belt buckle and commented, rather inanely and probably in a quavering voice: "Wait a minute." Quavering or not, I was poised and steeled to drive the bayonet into his body

Transcript

[page 8] at the first aggressive movement on his part. He obviously sensed that, for he waited very quietly and both of us silently, the bayonet point at the pit of his stomach, until the corporal of the guard arrived. The next day I heard the man telling someone else confined in the guard tent that a sentry came near killing him the previous night. He was quite correct and maybe the word spread, or perhaps he was the only one who attempted to slug sentries, for I heard of no more cases of the sort. As for me I learned a lesson I remembered in reference to others -- there is no one in the army more dangerous than a scared recruit. A battalion of the 13th Infantry was at the Camp from Fort Leavenworth, [Kansas], where that regiment was then stationed to serve as a model for the state troops. Mostly it was a good example -- a well drilled organization, its men swarthy with the sun and apparently tough as nails. But I remember their crap games, with a great many $20, $10 and $5 gold pieces on the blanket, for the regular army at that time and for years afterwards paid in gold. And I discarded my ill-fitting uniforms and replaced them with with modern breeches, leggins and khaki blouse purchased from miscreant members of the 13th trying to raise funds by sale of their uniforms. Back home again, and not quite such a recruit as national guardsmen of the day went, I became one of the nucleus of enthusiastic young soldiers which kept the guard alive. Since for economic reasons I still could not go to college, where the military training of Missouri University interested me more than anything else anyhow, and lacking the political influence necessary to secure an appointment to West Point, I put all my spare time, thought and energy into military work and study. In the spring I became a corporal and at the annual

Transcript

[page 9] inspection apparently did very well in a little quiz that the inspecting officer conducted for noncommissioned officers afterwards. Col. W.K. Caffee, who as previously mentioned had commanded the regiment during Spanish-American days, was present and at the conclusion of the examination gave me some kind words of praise. It was most encouraging to me, and its effect lasted for a long time. It has always been a lesson as to how much a few encouraging words can do for one who is trying. There was a noncomissioned officers camp in 1910, with all the noncomissioned officers of the regiment gathered together into two provisional companies for training at Nevada under the tutelage of the 13th U.S. Infantry. The affect was most healthful. There was also a maneuver that year at Fort Riley which I, for reasons connected with my civilian employment was unable to attend. This fact I always regretted since it is my observation that every bit of military experience, however tiny, is of ultimate military value. In the spring of 1911 I became a sergeant and was immediately made quartermaster sergeant - the equivalent of supply sergeant of later years -- and served as such at the 1911 encampment at Nevada. This was uncongenial work but doubtless educational and was the more difficult for me in the field since I acted as duty sergeant besides. The year 1911 was important to my military training in another way. I began interviewing old soldiers and studying the official records of the Union and Confederate Armies to write a serious of newspaper articles about civil war engagements and skirmishes in my home county. This interest continued for years, resulted in publishing a modest volume on this field in 1923. Since war changes only as weapons and circumstances change, I feel that many important lessons in irregular and guerrilla warfare lie hidden and neglected in the dusty tomes dealing with such phases of our own civil war. When the 1911 drill regulations came out I and a group of

Transcript

[page 10] fellow enthusiasts purchased some of the first copies issued by the Army and Navy Journal and studied them most carefully, trying them out in our own little nucleus on Sundays and any night in addition to drill night we could get possession of the armory. Our efforts were soon helped by the War Department which sent drill sergeants from line regiments to be stationed for a time with National Guard units for instructional purposes. We first had one named Johnson from Company A, 15th Infantry, andlater one named Foster from the Fourth Infantry. These men had committed the regulations to memory and we did the pertinent portions likewise. This was of assistance to me until after the first world war. I can still quote paragraphs from memory. In the summer of 1912 our Second Missouri Infantry was sent to Kansas to participate in maneuvers -- the Seventh U.S. Infantry stationed at Fort Leavenworth, our regiment, and a squadron of the 15th U.S. Cavalry, all commanded by Col Daniel Cornman, maneuvering against the Kansas and Oklahoma National guard regiments, the 13th Cavalry, then at Fort Riley, and some other regular artillery units. It was both an interesting and worthwhile maneuver, involving actual marching, bivouac and simulated combat over some 60 miles of Kansas terrain, terminating at Lansing, south of Leavenworth, [Kansas]. Still a combination, supply, mess and duty sergeant, I hada busy time. Long [ms illegible: 3 wds] One unpleasant featuredof the maneuver for me was connected with hard tack which with raw bacon was the nearest equivalent of the day to the C and K rations of the second world war. We breakfasted one morning at 4 a.m. and did not have a cooked meal again until the days maneuver was over about 5 p.m. IN our haversacks we had hardtack and raw bacon. I ate maybe a box of hard tack. It swelled after I ate it. The result was uncomfortable in a big way, as I recall, and as we bivouacked that night east of the Kansas State Pententiary I groaned in agony.

Transcript

[page 11] The maneuvers were reasonably realistic and made the more interesting because of an abundance of blank cartridges issued the men. In my opinion they were excellent training. The Mexican troubles were already absorbing the attention of mostvregular troops and as I recall no more combined army and national guard maneuvers were held. Even after the first world war they were not resumed on any large scale until -- if my memory is right -- about 1937. Our army was sadly in the doldrums to permit any such long intermission of a training feature so important. By the summer of 1912 I had reached a place where national guard activities -- however much increased interest the federal government was manifesting and howevermuch additional clothing and equipment was arriving -- ceased to satisfy me. I decided either to enlist in the regular army in the hopes of gaining a commission in the Philippine Scouts or to join one of the factions in the Mexican revolutionary troubles in order to get war experience preparatory to service in the American army. My mother -- my father had died when I was two years of age -- agreed I should join the regular army. Wisely she felt that a young man with a trend like mine had better get into the army and stay there. She had no enthusiasm about Mexico yet offered no objection. She could see the value of war experience for a soldier. I am proud of my fine Spartan mother -- an ideal mother for a soldier. I am only sorry that a more or less erratic military career failed to live up to her probably hopes and expectations.

Transcript

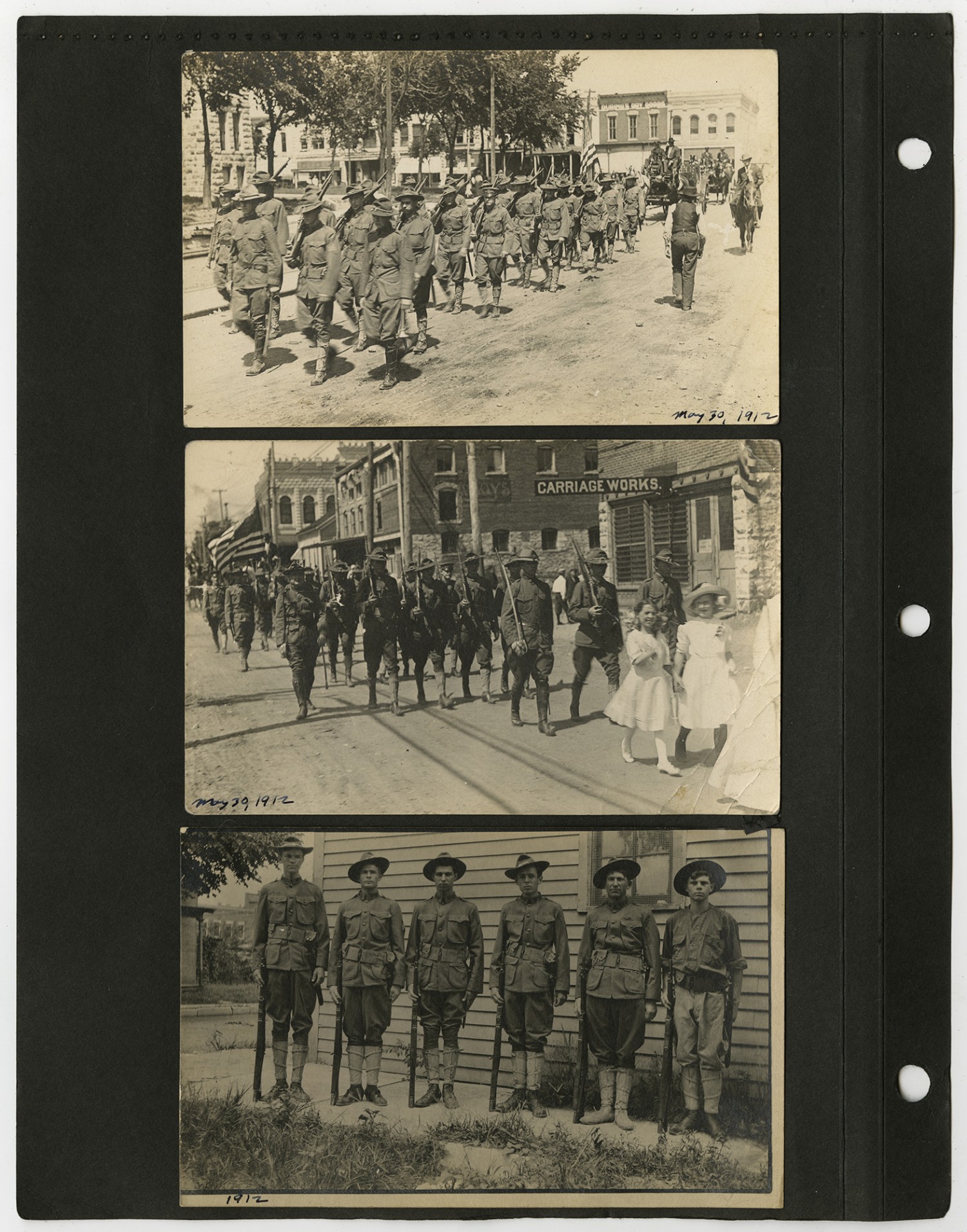

[photograph] Decoration Day 1910 [photograph] 1911 [photograph] 1912 M.R. Schrantz Ward L Schrantz

Transcript

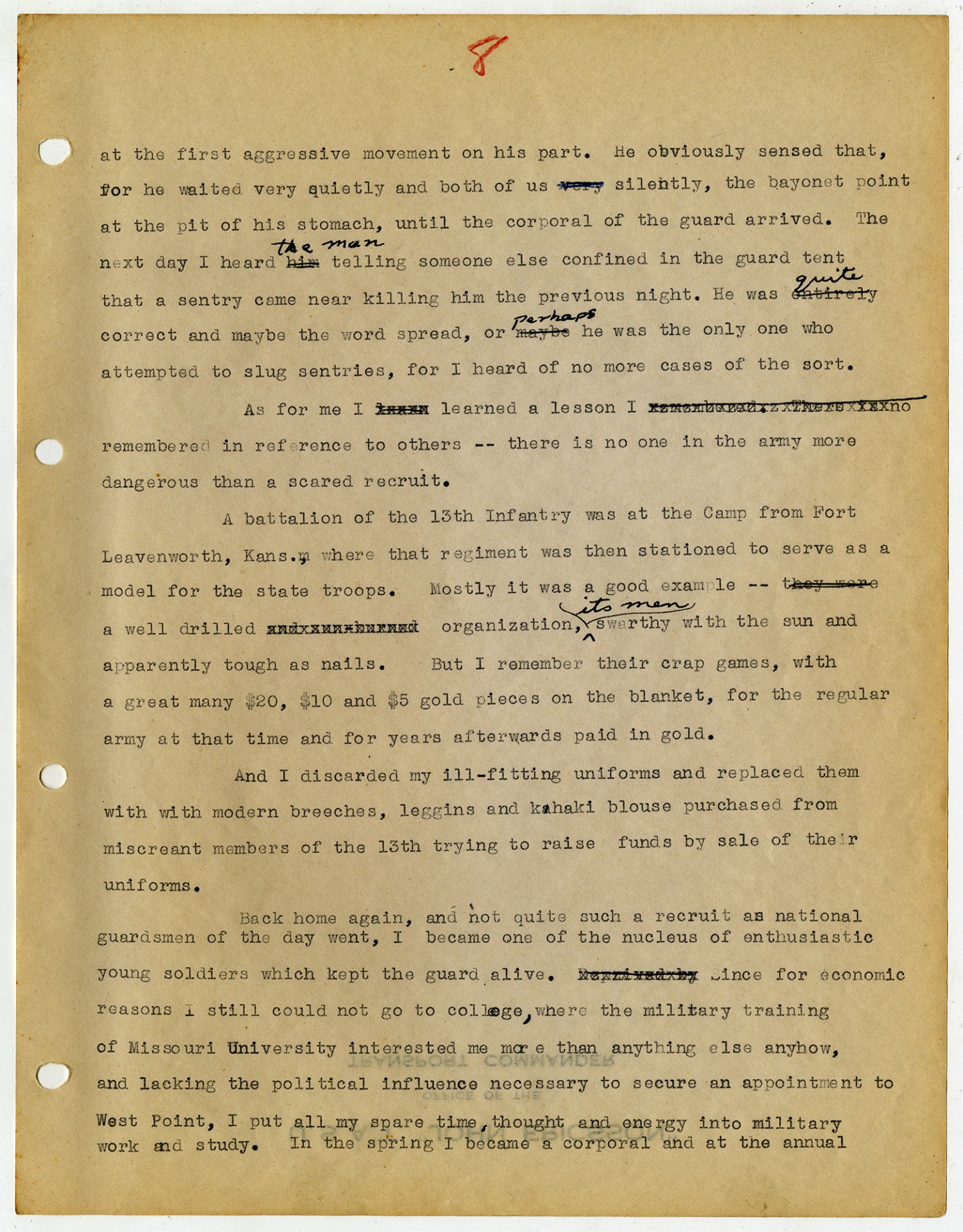

[photograph] CoA Mo NG July 3 [1910] [photograph] N.G.M. Nevada [photograph] Decoration Day 1911

Transcript

[photograph] Lakeside 1911 [photograph] Nevada Camp Clark 1911

Transcript

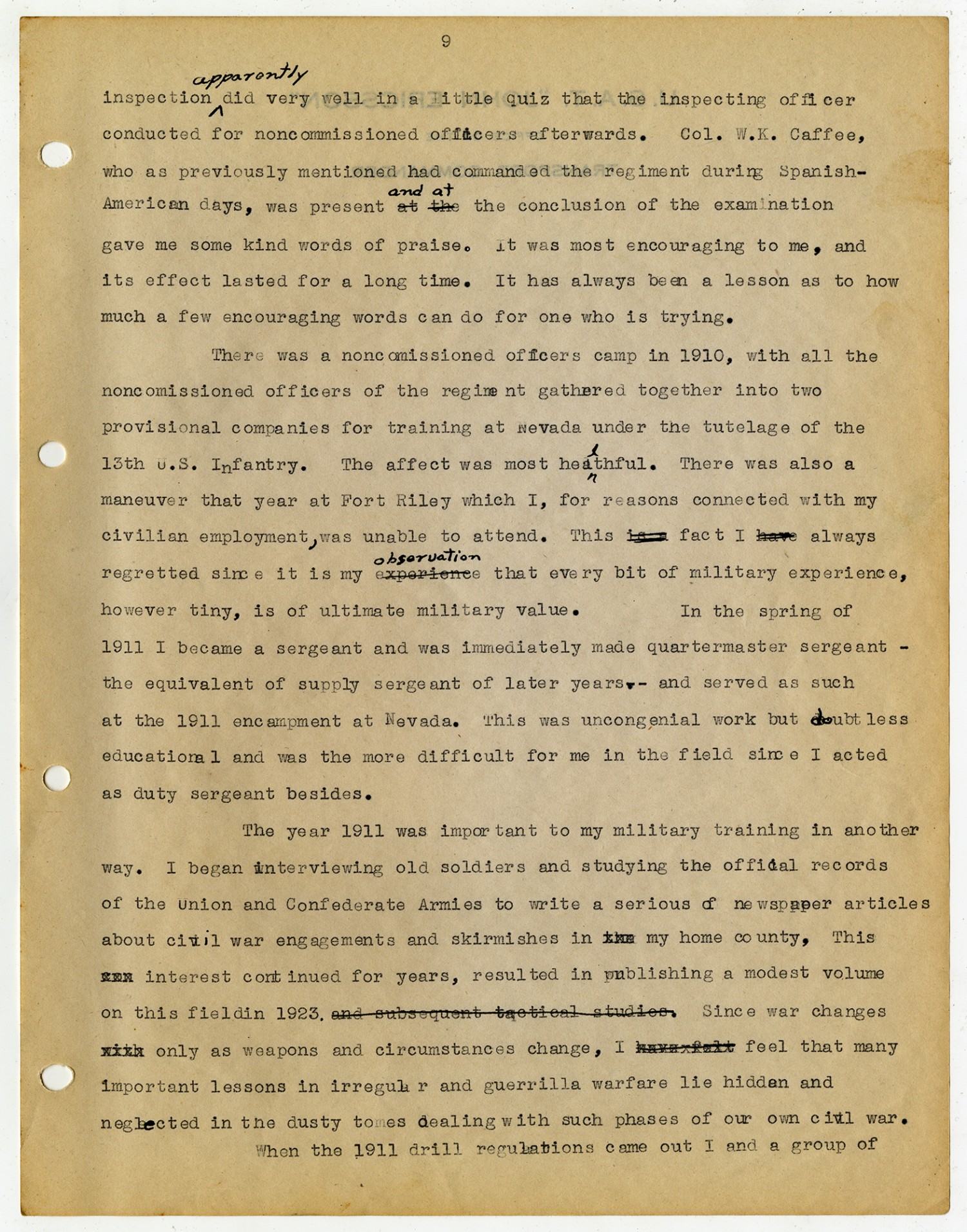

[photograph] May 30, 1912 [photograph] May 30, 1912 [photograph] 1912

Transcript

[page 12] My application for a discharge from the national guard to join the regular army being slow to go through, I resigned from the newspaper where I was employed, visited for a time with abrother in southwest Oklahoma, and then went to El Paso to look into the matter of joining in the wars in Mexico. My original interest in the Mexican wars had hinged in part on my sympathy for Francisco Madero in his successful revolt of 1910 and 1911 against President Porfirio Diaz. It seemed to me -- quite ignorant of details as I was -- that he had not dealt fairly with the leaders who had helped him to make that revolt successful. When Pascual Orozco raised the standard of revolt against him in 1912, Tracy Richardson who lived at Lamar, [Missouri], who once had been a member of the Second Missouri Infantry in which I had had my national guard experience, and who later had served under Lee Christmas in Nicaragua, gained a good deal of publicity as a machine gunner in Orozco's army. This gave me a rather favorable impression of the Orozco effort. By the time I reached El Paso the Orozco revolt was broken and such of his former forces as remained were in the field only as bandits under the name of "Colorados" or, as Americans called them, "Red Flaggers." It did not take much enquiry around El Paso to decide me that they were not the right side to be on anyhow. But I decided to go over to Juarez to take a look, although El Pasoans to whom I talked advised me that just then was a good time for all good Americans to stay on the American side of the line. In point of fact the only Americans I saw in El Paso that day was an old Iowa couple looking at the bullet-chipped statue of Benito Juarez, and an American post card salesman who told me that it was unwise to wander about Juarez alone.

Transcript

[page 13] One of the first things I did in Juarez after looking at the monument and church was to wander down by the jail, garrisoned and loop-holed for rifle fire. This was interesting and I stopped to stare. In the Mexican army those days the women constituted the commisary department, each man being paid daily and his wife, or the woman camp follower who served as such, getting and preparing food for him. It was lunch time and these women, some far gone in pregnancy and others with children accompanying them, were bringing food to the soldiers. A stack of Mauser rifles inside the main entrance interested me also. My acquaintance with military files was limitedto the 1903 Springfield and the obsolete 1872 Single-shot Springfield. All this display of interest was no doubt indiscreet and the sentry studied me suspiciously. I decided it might be as well to walk on. Walking on past the jail about a block I found nothing but adobe houses and turned back. As I neared the jail on my return the sentry called out an officer. The two studied me closely as I passed. Despite an uneasy conscience caused by the fact I had come down there in expectation of bearing arms against their side, I ambled past, trying to look as innocent and unconcerned as possible. The officer apparently decided I appeared harmless and so I was not stopped. Otherwise it is possible my future might have been an unhappy, the Mexican custom of the time according to reports, being either to shoot suspects or to put them in jail andforget about them. This little experience caused me to remember the old post card man and seek his counsel. He told me that the regular soldiers, clad in blue grey such as those at the jail were a part of the army that President Madero had taken over from the Diaz regime. Many of them, he surmised, ought to feel at home garrisoning that jail since they had been recruited from jails in the first place. The rest of the soldiers in town, those

Transcript

[page 14] wearing khaki, were Maderista volunteers -- mounted troops who were largely ranch hands who had volunteered to help Madero, a good many of them English-speaking and from the Mexican population on the American side of the border. He suggested that if I was determined to look around the town that he get one of those -- a good many of whom he knew -- to show me about. To this I was agreeable. A pleasamt young Mexican who in consequence I soon had as a guide told me that his name was Umberto Tabares and that he had worked on a ranch near Marathon, Texas, until he joined the Maderista volunteers. He thought he was to fight for Mexico, he said, but that they way it was there was no fighting at all. The Mexican regular army commanders would not let them fight the red flaggers about the town. They would be sent out from time to time but once outside the town some distance, would be required to halt and do nothing. In his opinion these regular army troops were not at all loyal to Madero. As for him, in view of that situation, he was considering slipping back across the border and returning to Marathon. His estimate of the situation, I noted later, was about correct. When Victoriano Huerta revolted against Madero early the next year, the federal troops in Juarez turned rebel, united with the Red Flaggers bands outside the city, and surrounded and captured the Maderista volunteers in the town. Accompanied by young Taberes I strolled through the local market and at my suggestion we walked up by the main barracks of which I had read in newspaper accounts concerning some of the fighting in Juarez. These were held by regular troops. Some kind of ceremony was in progress, possibly guard mount Gaily-garbed buglers and some troops were maneuvering in the

Transcript

[page 15] street, then marched back inside where a considerable body of troops were in formation. We stood across the street opposite the entrance looking in. A portly officer of upper middle age came across to us and engaged my Maderista guide in a wordy exchange, the Marathon cowboy holding up his end of it quite as boldly as if he had been a dignitary of the old army himself. Finally the officer turned away and Tabores turned to me. "He says we can't stand here," he commented. We walked down to the corner, stayed there until the music stopped he accepted my offer to buy a dinner if he would show me a place and handle the conversation. He led me to a hotel, argued for awhile with a fat woman in a hotel courtyard who regarded us with obvious suspicion but who eventually agreed to serve us. A waiter stood behind our chairs thrusting lined-up dishes, hot with pepper, in front of us as we cleared the contents from the preceding one. An additional dish of pepper sat in front of us, and since I did not care for mine in view of my feeling there was already a superabundance in the food, my companion added my spare seasoning to his in flavoring his own food. The waiter impressed me as being there partly to listen to our conversation, and it was with some relief a short time later, after I had told my guide good-bye, that I returned to the American side of the line again, being searched for firearms by the bridge guards as I had been on the way over. That night I was on an east bound Texas Pacific train, pumping a discharged member of the Second Cavalry about the fight at Bud Dajo, in Jolo, in which he had engaged shortly before returning to the United States. And I was impressed when somewhere near Fort Hancock, a couple of armed cavalry guards passed through the car, carefully

Transcript

[photograph] Prison, Juarex, [Mexico]. [photograph] Oh You Insurrectos [photograph]

Transcript

[photograph] Ruins of City Hall. Juarez, [Mexico] Rebels in action

Transcript

[postcard] Church of Guadalupe, C. Juarez, Mexico. In 1549 Spanish explorers reached the Rio Grande, founded El Paso del Norte and established the Church of Guadalupe. Infinite labor was expended in the hand carvings of the beautiful ceiling and altar of gold leaf. The bells were brought from Spain and for almost four centuries have called the faithful to worship and have marked the hours of the day and night. On September 16th, 1888, in memory of Benito Juarez, the founder of Mexican Independence, this quaint old City was re-named Ciudad Juarez. [postcard] Monument Benito Juarez, Ciudad Juarez, Mexico. [photograph] [ms illegible: 1 wd] Para Recivir A Rabago

Transcript

[postcard] "Aduana" Mexican Custom House, C. Juarez, Mexico. This building will ever by pointed out as being the one in which President Diaz of Mexico banqueted President Taft. $20,000 was expended in fitting up the banquet hall. [postcard] A general view of El Paso's business section, looking west on San Antonio St. The mountains to the left are on the opposite side of the Rio Grande and in Old Mexico. [photograph] Warren Hancock, Troop L, 2d U.S. Cavalry

Transcript

[page 16] scrutinizing each passenger, I supposed they were looking for Mexican bandits or suspicious characters. My companion grunted. "Showing off," he surmised. Back home I found my discharge from the national guard waiting for me, went to nearby Joplin, applied for enlistment and that night with one other recruit went to Jefferson Barracks where after final physical examination we were sworn in with a group of men from various other recruiting stations. It apparently frequently happened that men applied for enlistment but their nerve failed them and at the recruit depot they did not want to join. The club the army held over their heads was that if they did not go ahead and take the oath they were guilty of getting railway transportation to the depot under false pretenses. The reluctant ones thereupon tried to fail the medical examination. One man in my group professed to be unable to read any letter of any size on the eye chart. And he could not hearing the ticking of a watch behind his ear or even loud whispers. "You can't see very well, can you?" said the medical officer. "No sire," answered the man, "I can't see skeercely at all." "And you can't hear very well?" continued the medico. "No sire. I can't hear skeercely at all." "Well," said the officer, "I guess you can see and hear well enough to soldier. Get over with that group of men who have passed." This was on October 23, 1912, and we enlisted for three years. On November 1 a new law went into effect by which men enlisted for seven

Transcript

[page 17] years -- either three or four with the colors and the rest in reserve. We congratulated ourselves on getting in just under the wire. Generally speaking, the recruits depot was something of an amusing nightmare. Recruit companies consisted of a training cadre of permanent party men -- "general service infantry," I think they were called -- and the recruits. The permanent party men lorded it over the recruits in a big way, impressing on the newcomers that they were the lowest of the low., A corporal ranked about as high as a colonel in the line and even a private was an important personage. As for us we officially and unofficially were "Cruts," so listed on the roster. One gathered that the one unforgiveable sin at that time in the army was being a recruit. I was rather surprised the first time I did a guard and became acquainted with some of the noncommissioned officers to find that thet were quite human and rather pleasant fellows when away from routine in barracks. Since I suspected that telling I had been a national guardsman would not add to happiness of life in the army, I carefully remained silent about any military background. Since obviously I already knew the recruit drill I was subjected to some appraising stares but no one questioned me. Presumably a man's past was his own business until he was exposed. But the noncommissioned officers evidently came to certain conclusions. One evening the corporal in charge of my squad room in the 27th Company, a man who never honored a recruit with anything but a scowl, came in to the room and direct to my bunk, affable and smiling. "Your name is Jones, isn't it?" he asked. "No" I said. "That is Jones yonder." He scowled at me as of old and smiled on Jones.

Transcript

[page 18] "Get your blankets," he said pleasantly as to an equal, not to a contemptible recruit, "we are going to the guard house." And so "Jones" who we soon learned, had served in the army before, deserted and reenlisted under a false name, passed out to prison and punishment. If there were any chaplains about Jefferson Barracks I never saw them but I went once to a religious service conducted by some ministers from St. Louis. They addressed us as if it seemed to me, we had been convicts in a penitentiary. A soldier in the ranks was not rated very high by ordinary civilians in those days and I have not doubt these good ministers regarded us as about convict social level. We did not see much of our officers but occasionally they gave lectures of one sort or another and since they talked to us as if we were soldiers and not mere recruits we were pleasantly impressed. Only one of these officers remains in my memory and of his talk only one section. He was a jovial old cavalry major named Quinlan Daniel P. Quinlan I think. "Don't get the idea that you are heroes because you are in the army," he told us. "No man is a hero just because he joins the army and no man is a hero in his first war. But if he ever volunteers to go back to a second war -- ah then he is a hero." The recruits in the 27th Company as I remember them was not a bad lot. My principal friends were a man named Percy Lang from Chicago who had been a cook on lake steamers, a quiet ex-laundryman named Dennis from somewhere, some six or seven years my senior, and a young farmer named Apple -- " 'Crut Apple" -- was always the first name called on our our roll call. Lang like I had enlisted for the infantry, Dennis was in forth coast artillery, and Apple for the cavalry. My own preferences were for the cavalry but I had a somewhat

Transcript

[page 19] exaggerated idea of the value of my previous infantry training and thought I would have abetter chance there. I wanted first to be in the infantry therefore, and second I wanted to get out to the Philippines. All the men at the recruit depot had enlisted for some particular arm or service and changing to any other was optional. Requisitions came to the depot from time to time for so many men of such-and-such an arm or service for such-and-such a point. IF there were not enough enlisted for such arm to fill the requisitions, others were invited to volunteer and many did. Everyone was anxious to get away, and services such as the medical corps for which few had signed up thus obtained their quotas. I was tempted once to transfer to the field artillery for there was a group going to the Philippines. Had it been a cavalry group I would have done so probably. But I held off, waiting in hope. My main fear was that I would be sent to the 7th Infantry at Fort Leavenworth, and my fear was based not on any objection to that famous regiment but to the fact that Fort Leavenworth was a bit too close to my own home. Could I have seen what the future held for the Seventh, I would not have minded. Less than a year and a half later that regiment boarded transports at Galveston for Vera Cruz while my own waited on the beach for orders that never came. In early December there came a bunch of requisitions for replacements and most of us "old timers" in the 27th Company moved out -- the infantry to Fort Bliss, the coast artillery to Fort Morgan, [Alabama], and the cavalry to the Third Cavalry on the Rio Grande somewhere. Bidding goodbye to Dennis and Apple, Land and I with a couple of carloads of others were soon speeding across Missouri, Kansas, the Texas Panhandle and New Mexico down to El Paso where a few short months before I had been pondering the idea of joining some army in

Transcript

[page 20] Mexico. Noncommissioned officers of the Jefferson Barracks permanent party conducted us on our jaunt so the atmosphere on the trzin was much the same as at the barracks except that we were happy and elated at being on the move. Our food was a bit scanty but I had ben in the national guard too long where it was still scantier at camps to grouse about that. I ate slowly, masticated the food thoroughly, and hence -- believing something I had read somewhere -- was better satisfied than if I bolted it. Carefully, from policies sake, I refrained from complaint. One evening as we crossed the Panhandle there was, for a wonder, plenty of hash. Just as we were finishing eating, the sergeant in charge came up the aisle and spoke to me. "Did I hear you say you were not getting enough to eat?" he queried. "You never heard me make any complaint," I answered truthfully. "I don't know whether I complained or not," spoke up Lang, "but anyhow I haven't been getting enough to eat." Someone carrying the receptacle with the hash was with the sergeant and the noncomissioned officer filled Lang's meat pan heaping full. "Now I want to see you eat that," he said. "Eat every bit of it." Lang ate the food leisurely -- all of the huge pile. Next he took a piece of bread, swiped up his mess kit with it and ate the bread. Then he spoke. "Sergeant," he asked, "May I have some more hash?"

Transcript

Arriving at Fort Bliss on the north edge of El Paso on [December] 7, 1912, the detachment of recruits from Jefferson Barracks were lined up near the railway and counted off to go to various infantry units. The troops at Fort Bliss and in the El Paso vicinity at that time consisted of the 22d Infantry, commanded by Col. D.A. Frederick, the first battalion of the 18th Infantry, and the Second Cavalry. Col. E.Z. Steever (or Brig Gen.) was in command of the whole. "Easy" Steever some of the soldiers good-naturedly called him, I learned later, because they thought he was too willing to accede to the request of El Paso for troops for parades. That Col. Steever might have had a sound military reason for making a display of his strength in El Paso whenever occasion offered in view of the disturbed conditions along the border did not seem to have occurred to anyone. But there were no parades while I was there, so far as I recall. Certainly my company participated in none. The infantry units had been sent to ElPaso from their home posts at the time the Orozco revolt started. The 22d was guarding the international bridges and had outposts at other key points along the border, with headquarters at Fort Bliss. The battalion of the 18th, as I recall, was all at Fort Bliss, as was all of the Second Cavalry at that time. The reason for the cavalry being at the post instead of on patrol, I was told, was that it had recently returned from the Philippines and had been filled up with recruits, whom it was necessary to train before going on anything even approximating active duty. In the assignment of recruits I was in the group allotted to the 22d Infantry and the genial sergeant major of that regiment, an old soldier named Jans, detailed several men including myself to Company F.. My friend Land went to Company C of the 22d where he soon became a cook

Transcript

[page 22] and so far as I have knowledge of his life lived happily thereafter in that capacity. Company F was stationed at Washington Park in East El Paso near the Rio Grande and we were taken there in a mule-drawn escort wagon jolting over dusty roads. From the high ground before we started downward I remember staring over the valley at the distant often captured Juarez, dominated by hills to the south so that it looked from there like it might have been founded with the specific purpose of making its capture easy. A noncommissioned officer in the wagon explained that we were joining the best regiment in the army and being assigned to the best company of that regiment. Capt. L.A. Curtis the company commander, he further asserted, was a fatherly individual, deeply interested in his men, and and an ideal officer under whom to serve. We were favorably impressed, particularly after we were told the same thing by other men of the company. It was a unit which believed in itself. Capt. Curtis, a slow-spoken Spanish-American war veteran 40 years of age, welcomed us himself, and we were then taken in charge by a heavily bearded, middle-aged first sergeant. Beards had gone out of military fashion before this but when the regiment left its quarters at Fort Sam Houston the preceding February he had stated that wasn't going to shave again until it returned -- and he hadn't. His whiskers gave a civil war aspect to the scenery. Company F was billetted, along with Company E, in a long adobe building at the front of the park in a long room evidently used in normal days for fair exhibits of some kinds. At the head of the bunk allotted to me was a huge crude mural of an ailing chicken with the words "Conkey will cure you." We were issued field equipment and rifles, with 30 rounds of live ammunition to carry in our belts

Transcript

[page 23] and we settled down feeling quite field-soldierish and warlike. Company F, we found, maintained an outpost about a mile to the west on the international line which here was a former channel of the Rio Grande, the river having cut a new channel inside Mexican territory. This was the region later called "the hold in the wall" and I have heard its ownership was disputed but at that time all south of the old stream bed was considered Mexico. From the outpost tent single sentries by day and double sentries by night patrolled a beat which on the west ran to the foundry and on the east along the old streambed to where it ran into the river. The company was low in strength and about a third of it was on duty nightly. It was with some disappointment that I learned that recruits were to be given special training a week or so before being turned to duty. My first glimpse at a regular army organization from the inside naturally interested me. The noncommissioned officers, unlike those at the recruit depot, were friendly and human. Most of them were old soldiers -- the junior of them being on his third three-year enlistment, and a number of them being veterans of the Spanish-American war 14 years before as well as the later Philippine campaigns. While the general educational level was low, by modern standards, there were exceptions in some obviously well -educated men whose presence in the ranks I presumed to be the result of love of soldiering or love of liquor, or both. It was only at pay-day they showed the liquor trait. When a private drew $15 a month, a corporal $21 and a sergeant only $30, normal sobriety was a necessity as well as a virtue. My own position in the company was pleasant from the start due to a reticence about the past which fitted in with military ideas

Transcript

[page 24] of the day. The reticance was entirely due to my feeling that it would be tactful to conceal a national guard background so long as I was new in the regular army but whatever interpretation was put on it by my new comrades the result was favorable. A man's past was his own business. What he had been or done in civil life id not matter; only what he was and did in the army. My first evening I had unpacked my gear from the Jefferson Barracks recruit bag to stow it away in a box underneath my bunk, my well-worn infantry drill regulations of national guard days was lying on my bunk. A sergeant picked it up curiously, and noted that I had torn out the flyleaf where a man usually wrote his name and organization. "Where did you get this?" he asked. "It is none I had left over," I replied. He grinned and asked no further questions, for this reason or others but I found myself accepted henceforth as a soldier instead of a recruit. Within a few days I was "turned for duty" and began to take my turn at border patrol. It was, properly, a patrol. though on each of Company F's patrol posts there was one man by day and two by night. Tours of duty were four hours on and eight off. By day I strolled along under cotton wood trees in which mistletoe was profusely growing, studied the Mexican side for alertly signs of activity and the American side curiously to observe the habits of the local Mexicans. And in the long tours at night there were long conversations with my companion about his military experiences or about his home regions. Under orders we carried our rifles with empty chambers but with a full clip in the magazine so that there was a minimum danger of accident but only a movement of the bolt necessary to prepare for action. I fell in the habit of a mountaineer friend and habitually carried my rifle in the hollow of my left arm. Orders were not to fire, even if fired upon, except in self-defense.

Transcript

[ms illegible: 9 wds]

Transcript

[page 25] The restraining order was not taken too seriously. The "except-in-self defense" clause seemed broad enough to cover all eventualities. To me it seemed that the duty itself was not taken as seriously as it might be. The first night I was on post from 10 to 2 a.m. and was amazed to see the 2 to 6 o'clock relief turn out with blankets. The nights were chilly and custom was for the men on number 1 post to the west to sleep in the foundry at the west end of the post and those of No. 2 relief to sleep in the plant at which El Paso garbage was burned which was within the territory of that patrol post. The only man of the whole outpost awake during those hours was the non-commissioned officer of the guard dozing over a magazine at a lantern much of the time at the guard tent within 50 feet of the border. My expressions of surprise drew amused rejoinder that there was no danger -- that the officers never came around after 2 o'clock. As for the Mexicans "those fellows know better than to attack Americans. Now if they were Filipinos, it would be different." I wondered, perhaps [ms illegible: 1 wd] f few years later if a [ms illegible: 2 wds] was responsible for the surprise of the garrison at Columbus, [New Mexico] by [ms illegible: 2 wds] This carelessness in patrol due to the bored attitude of the rank and file was only a passing phase and ended with renewed activity across the line which caused renewed activity of our own officers in checking up. But while it lasted I was never on the 2 to 6 o'clock relief, always trading it off, when I drew it, to someone who had drawn the 10 to 2 watch and preferred the later one where they could sleep. As for me I tried to be alert, being young and comparatively ambitious, and once for a few moments I thought my vigilance was about to be rew3arded by action. Going on patrol as a single sentry at 6 o'clock in the morning I was strolling along No. 2 post when I saw to the east two horsemen in civilian clothes, ride toward a Mexican farmhouse on the American side just to the east. In the early morning light I caught the glint of the butts of rifles in boots attached to their saddles.

Transcript

[page 26] My instructions covered a situation such as this appeared to be. Working my rifle bolt and slipping a cartridge into the chamber, I ran across the field to intercept them, the safety catch up and with my thumb against it to knock it down to "ready." The horsemen drew up to wait for me without making any motion toward their weapons. As I heared them I saw they were American, and smiling. In fact I had already met both of them One, I knew, was a retired first sergeant of cavalry and the other a Texan of gun-antecedents. They were men of the customs border patrol which at that time were uniformed save as their heavy revolvers in western holsters and their Winchesters indicated their calling. My recognition of the two was attended with a combination of relief and disappointment but happily not of chagrin since, without mentioning it, they obviously considered my zeal in intercepting a couple of gunmen as most commendable. These were indeed gunmen, though on the right side. In all the history of border patrol of that and subsequent periods I suppose there was no duty as dangerous as theirs. As activity increased we saw more and more of them. Though fewin numbers they undoubtedly were a very effective guard against the kind of banditti then along the border. I felt at the time that the army patrol as I saw it needed some such supplementation. As the weeks went on, alarms of one sort or another became not unusual, usually reaching us in the form of an alert for which we knew no reason, requiring that all men off duty remain in camp available for call. One day when I was on outpost duty we noticed a number of horsemen riding rapidly back and forth near a clump of trees a mile of so south of the border. A few moments later a cannon opened fire toward to the south and for about four hours shots were fired at intervals

Transcript

[page 27] but he hard no other firing, and all we could see was the flash and smoke of the discharge and an occasional horseman riding off rapidly to one flank or the other. A few American civilians drifted down to the border to watch what was going on but that apparently was all the interest the affair created. It was not even mentioned in the usually voluble El Paso papers -- much to my regret since I had spent most of the time perched in a tree observing proceedings. One night we had a brief false alarm which taught me a lesson. I Had been on first relief, had come off post and had turned into my bunk at a little after 11 o'clock, fully dressed of course in accordance with regulations on the subject but unbuckling my cartidge belt for greater ease. About 11.30 a rattle of shots on the Mexican side close at hand brought brought us out of our sleep, off our our bunks and out in the open in an instant, rifle in hand and ready for whatever might happen. But there really was no cause for excitement. A wedding celebration was in progress at a Mexican house just across the dry river bed and, Mexican fashion, some of the guests were expressing their hilarity by firing into the air. And it was just as well for me that this was the case for about the time the shooting was explained to us I discovered that I had left my belt of cartridges on my cot and had answered the alarm without ammunition other than the five rounds in the magazine of my gun. I slunk back in and put on my belt while the others were staring at the house and so no one noticed -- and I saw no occasion for mentioning it. One morning a little after daylight when I was shivering up my beat on the Number 1 post about three blocks west of the guard tent, two mounted Mexicans wearing long serapes muffled about their faces rode across the border from the direction of an adobe hut where I had been told two cowpunchers lived who worked

Transcript

[page 28] on the American side. I let them pass unquestioned with a "good morning" exchanged in English with the leading one. After they passed it occurred to me that I should have made them throw back their cloaks so that I could see that they were unarmed. It was not too bad a slip since our orders principally concerned the smuggling of arms into Mexico but obviously armed men should not be permitted to cross either direction and the men might have been wearing revolvers under their cloaks. I reflected that I too was getting careless. That night in the El Paso Herald was an item saying that Pancho Villa, formerly a bandit but later an officer in the army of Madero and still later a prisoner in the penitentiary at Chihuahua City where he had been confined by Gen. Victoriano Huerta, had with the assistance of some friends made his escape from the prison and that morning with a single companion, both fully armed, had crossed the border and was then at such-and-such a hotel in El Paso. Villa was not as prominent at that time as he later became, but I have always wondered if I let an opportunity to [ms illegible: 1 wd] words with that redoubtable chantry escape me. Soon after this a considerable band of Red Flaggers chased the federal garrison out of Guadaloupe, some distance down the river, began to talk about an attack on Juarez and sent patrols up toward it. A detachment of federal cavalry men -- five or six men as I recall it -- took post at the Mexican end of the unguarded ford just south of Washington Park, and there was considerable riding of patrols back and forth. A flag was flying on some white buildings some distance south of the river and I suppose troops were stationed there, probably the force from which the ford outpost came. Partly for exercise and partly out of curiosity I was accustomed to stroll along the American side down there when off duty and I recall that the Mexicans at the ford were rather careless with firearms, firing at objects in the river occasionally and

Transcript

[page 29] in such direction that now and then a richocheting bullet which had probably struck a sandbar went singing off on the American side to the east ward somewhere. Around a third to a half o four company of about 60 men were on guard duty daily and the remainder not on detail of some sort drilled, maneuvered or took short practice marches in the forenoon. One of these jaunts , one morning, was eastward along the border road leading toward Alfalfa a few miles further on. As we rested just west of the village there came from the brushland in the valley across the Rio Grande the sound of a rifle shot, followed by four or five more, increasing to the patter of a lively little irregular fusilade which soon dwindled away into a few scattering shots then ceased. Mexicans in vehicles of one sort or another going by us toward El Paso were thrown into consternation. Quite possibly they thought our presence had some connection with the firing and that bullets might soon be coming in our direction. Some of them flailed their burros into sharp trots, others impelled their animals into accelerated speed by gouging them with sharp sticks where it would do the most good -- the whole group clattering down the road toward the city trying to get away from our vicinity as rapidly as possible. Soon we were hiking back to our position at Washington Park but we enlisted men at least never knew what started the fireworks. Probably a red flagger patrol had clashed with some of the federals. That afternoon I strolled down by the river as usual. The federal outpost, I noted, was no longer in the bunch of willows on the other side of the ford. As I stood there, whittling on a cane I had cut from the brush a few moments before, I noted seven mounted men trotting around the bend of the river on the Mexican side of the stream to the southeast. They were in single file with intervals of about 20 paces between horses and I

Transcript

[page 30] could not see what uniform, if any, that they wore, For some distance around where I was standing the ground was perfectly flat and bare, as this was the low bank and the river flowed over it in time of flood. I was therefore quite visible to the approaching patrol and when it had drawn a little nearer, the leader, followed by the others in file, veered away from the course of the river and directly toward the clump of willows in such manner as to keep it between them and me. I did not like this maneuver very much, and liked it still less when I saw through the willows as they approached that they were clothed in nondescript garb, no part of which suggested either the khaki of the Maderista volunteers or the bluish grey of the Mexican regulars. Obviously they were red flaggers. I remembered with some disquiet that a day or two before some of Salazar's band had fired at some members of the 13th Cavalry in the Guadaloupe vicinity for preventing recruits from crossing to join them, and I would have been glad if I at least had had my rifle with me. However since retreat would have been undignified and perhaps not entirely to the credit of the American army I remained where I was, whittling on my stick and endeavoring to appear indifferent. The patrol rode up to the clump of willows and the leader drew rein behind it, staring at me over the top of the bushes. Then drawing a rifle from a boot on the right side of the saddle he dismounted, threw his reins to a companion, and with his rifle and free hand punching away the willows, came through the clump and stood staring at me across what seemed at the moment a lamentably narrow stream. I continued to whittle, but with one eye fixed on a nearby depression in the sand which I figured I could reach quite promptly if he raised the gun to his shoulder. But either he decided that I was harmless or it was not his day to shoot at

Transcript

[page 31] Americans, for after a short scrutiny he returned to his companions; all dismounted, and began to prepare a meal. I then felt free to continue my stroll. About an hour later the men departed, trotting toward Juarez. The only guard maintained at Washington Park itself during this time, completely unprotected though it was in the direction of the ford directly to the south. was a single sentry post. Three privates and a non-commissioned officer were detailed alternately from E and F companies for this duty, the N.C.O. going to bed at night, though fully clothed, and the sentries waking each other up when time came for the reliefs. During day light hours the sentry walked back and forth inside the building to prevent any soldier inclined to do so from taking out any bundle of clothing to sell to augment his $15.00 a month pay. But at night his post was outside the southern portion of the long adobe building -- the section of it occupied by troops - encircling the southern end and cutting through the lighted sally-port in the center. At each round he also was required by his orders to walk south of the buildings a short distance along the front of some adobe stables where a few race horses were kept. For some reason the custom was for this quarters-guard to be armed with a revolver instead of a rifle - the 38-caliber service weapon of the time being passed from one sentry to another at the end of the period of each on post. The first time I walked this post there had been five cartridges transmitted. The night after I saw the red-flagger patrol at the ford and I went on this duty there was only two. This seemed to me a rather meager armament in troublousbtimes for a sentry who was the only man awake out of a hundred or so soldiers sleeping in a rather exposed situation, but having no inclination to invite ridicule of accusation of timidity by

Transcript

[page 32] protesting I accepted the situation as I found it though I would have been much more comfortable if I had carried my rifle and worn the cartridge belt that hung by the head of my cot inside. There was more or less movement, all the early part of my tour of duty, along the Alfalfa road, north of the park and this was somewhat disquieting since usually at that hour there was little. Also my youthful imagination pictured lurking red-flaggers in the blackness by the stables and I walked that part of my post with revolver in hand. Now the Alfalfa road north of the park was paved with about a nine-foot strip in the center and along about two a.m. while in front of the stables I heard a tremendous clatter of galloping horses coming down this highway from the east. It sounded to me as if half the red flaggers in Chihuahua had crossed the border and were galloping in. I raced for the sally-port, believing that if I ran fast enough I could reach it by the time the horsemen did and make a two-cartridge stand in this entrance, deriving gloomy satisfaction from the thought that after I had done so my exit from the world would be directly in front of my captain's door, his quarters opening up on this entrance. My first and more practical purpose however was to reach the sally port in time to throw off the light switch so my brief resistance would at least have the protection of darkness. As I reached the sally-port and ran through with revolvers in hand the horsemen swept by to the north, continuing toward town. They were American cavalrymen, and only five or six of them at that. And rankest recruits too, I reflected sourly -- who else would gallop horses on concrete when there was gravel road alongside. It was time for my relief. I went in, woke up the sentry whose turn was next, gave him the revolver and two cartridges, felt for my rifle and ammuniation belt to see that they were convenient to my hand, and went to

Transcript

[page 33] sleep. The next morning I was told that soon after I had gone off duty all the border posts had been alerted with word that the red flagger forces south of the Rio Grande had started movement westward toward Juarez. The patrol which had given me a few pseudo-heroic moments quite possibly had been carrying information of some sort. The red flagger bands, I further learned, had not come west along the river as far as Washington Park, turning south instead when about opposite the Company E outpost at San Lorenzo ford. As soon as I was relieved from guard I borrowed the first sergeant's field glasses and climbed to the top of a shoot-the-chutes structure at the south end of the park to see what I could see across the river. It was not much. There was a distant scurrying about of mounted patrols, apparently federal, but no signs of conflict. A little later I saw the smoke of four trains moving south from Juarez on the Mexican Central Railway and in about an hour the occasional sound of a distant cannon could be heard, probably "El Nino", a light piece mounted on a flat car and frequently mentioned in the newspapers as used for patrol on the railway. So far as I ever heard there was no real fighting -- and the El Paso newspapers would probably have had the story if there had been. My recollection is that the reporters said that seven troop trains had been sent out but that the red flaggers continued moving to the south and the federals returned to Juarez. A period of quiet followed this brief flare of excitement. The first battalion of the 18th Infantry had left El Paso for Fort D.A. Russell, (later Fort Francis E. Warren) at Cheyenne, [Wyoming]. The 22d Infantry, it seemed, was also scheduled for station at that post instead of its previous post at Fort Sam Houston and much of the company gossip had to do with the possibility of such a move.

Transcript

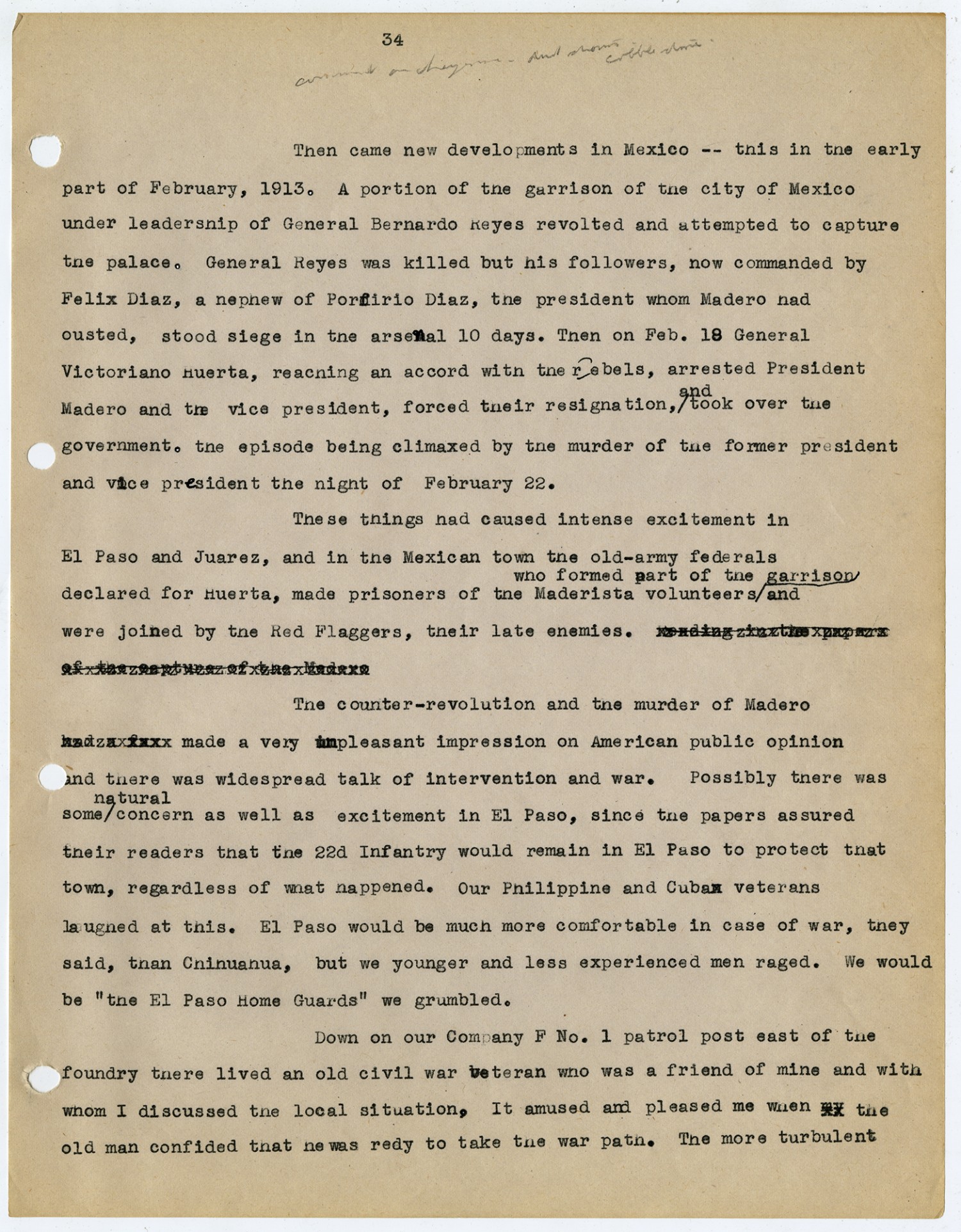

[page 34] Then came new development in Mexico -- this in the early part of February, 1913. A portion of the garrison of the city of Mexico under leadership of General Bernardo Reyes revolted and attempted to capture the palace. General Reyes was killed but his followers, now commanded by Feliz Diaz, a nephew of Porfirio Diaz, the president whom Madero had ousted, stood siege in the arsenal 10 days. Then on [February] 18 General Victoriano Huerta, reaching an accord with the rebels, arrested President Madero and the vice president, forced their resignation, and took over the government. the episode being climaxed by the murder of the former president and vice president the night of February 22. These things had caused intense excitement in El Paso and Juarez, and in the Mexican town the old-army federals declared for Huerta, made prisoners of the Maderista volunteers who formed part of the garrison and were joined by the Red Flaggers, their late enemies. The counter-revolution and the murder of Madero made a very unpleasant impression on American public opinion and there was widespread talk of intervention and war. Possibly there was some natural concern as well as excitement in El Paso, since the papers assured their readers that the 22d Infantry would remain in El Paso to protect that town, regardless of what happened. Our Philippine and Cuba veterans laughed at this. El Paso would be much more comfortable in case of war, they said, than Chihuahua, but we younger and less experienced men raged. We would be "the El Paso Home Guards" we grumbled. Down on our Company F No. 1 patrol post east of the foundry there lived an old civil war veteran who was a friend of mine and with whom I discussed the local situation. It amused and pleased me when the old man confided that he was ready to take the war path. The more turbulent

Transcript

[page 35] part of the Mexican population of El Paso was preparing for hostilities against the American population in case of war, he said, and he had made plans all of his own. "I have a mighty good gun and know how to use it," he confided. "There are five Mexicans in this part of town I am going to get just as soon as a war starts. They have made their brags but they are going to have to shoot fast if they shoot first when I go after them." President William H. Taft Had only a couple weeks of his term of office remaining -- since President-elect Woodrow Wilson would be inaugurated on March 4 -- but it was reported that he would order the concentration of an American division in Texas ready for his successor in case he decided on intervention. This interested us. A paper divisional organization announced some time previously had listed the 22d Infantry in the 2d Division. Maybe- just maybe. A morning or two later after calling the roll as usual at reveille, First Sergeant Elbert C. Russell stared at us belligerently with bristling beard, a sure sign that something of important would be forthcoming. "Hurry over and get your breakfast, then roll your packs and fold your cots," he said. "We are going to move." A short time later as we completed our preparations, a troop of the Second Cavalry rode up at Washington Park. A detachment moved down to relieve our outpost. The remainder dismounted and unsaddled and carried in armloads of saddles, rifles, sabers and other paraphernalia, while the escort wagons which had accompanied it began unloading supplies at our kitchens. Our own escort wagons were being loaded at the same time and

Transcript

[page 36] I was busily engaged in this activity. Swinging up a huge cotton sack of navy beans I glanced at a tag on it. "Not ours," I commented as I lowered it. "Troop L, Second Cavalry." "Throw it is! Throw it in!" forcefully whispered our mess sergeant. I did, and so we were ahead a sack of beans and the horse-soldiers short. That night at Fort Bliss where the regiment was being concentrated was a most miserable one. A merciless wind whipped around the shoulder of Mount Franklin, driving before it a cold steady rain. Shelter tents would not stay up in such a gale with only loose sandy soil to hold tent pegs and we sought what shelter we could. I huddled in the lee of a canvas sidewall of an old kitchen but, thoroughly drenched, gave up the fight in due time and joined hundreds of other men gathered around huge fire down by the railroad track. I slept toward morning and was awakened by some women searching for acquaintances, or husbands maybe. Just then first call sounded. "First call for a move," commented a grizzled corporal grinning grimly. "There's an old saying. 'It pays all debts and divorces all women'." There was a day of shifting about and waiting, and night found us down in east El Paso somewhere shivering with cold and still waiting for cars. Our cooks, installed in a baggage car, were drunk and supper consisted of cold beef sandwiches without the hot coffee we craved. One of them kept muttering over and over inanely in answer to complaints: "Well, we're all American soldiers, aren't we?" He was an old soldier who had served with Funston in the 20th Kansas in the Philippines and a friend of mine -- but I did not feel friendly to him that evening. Confusion everywhere, discontent, oaths. "The army on the move," sneered someone caustically, "The army on the move."

Transcript

[map of Mexico]

Transcript

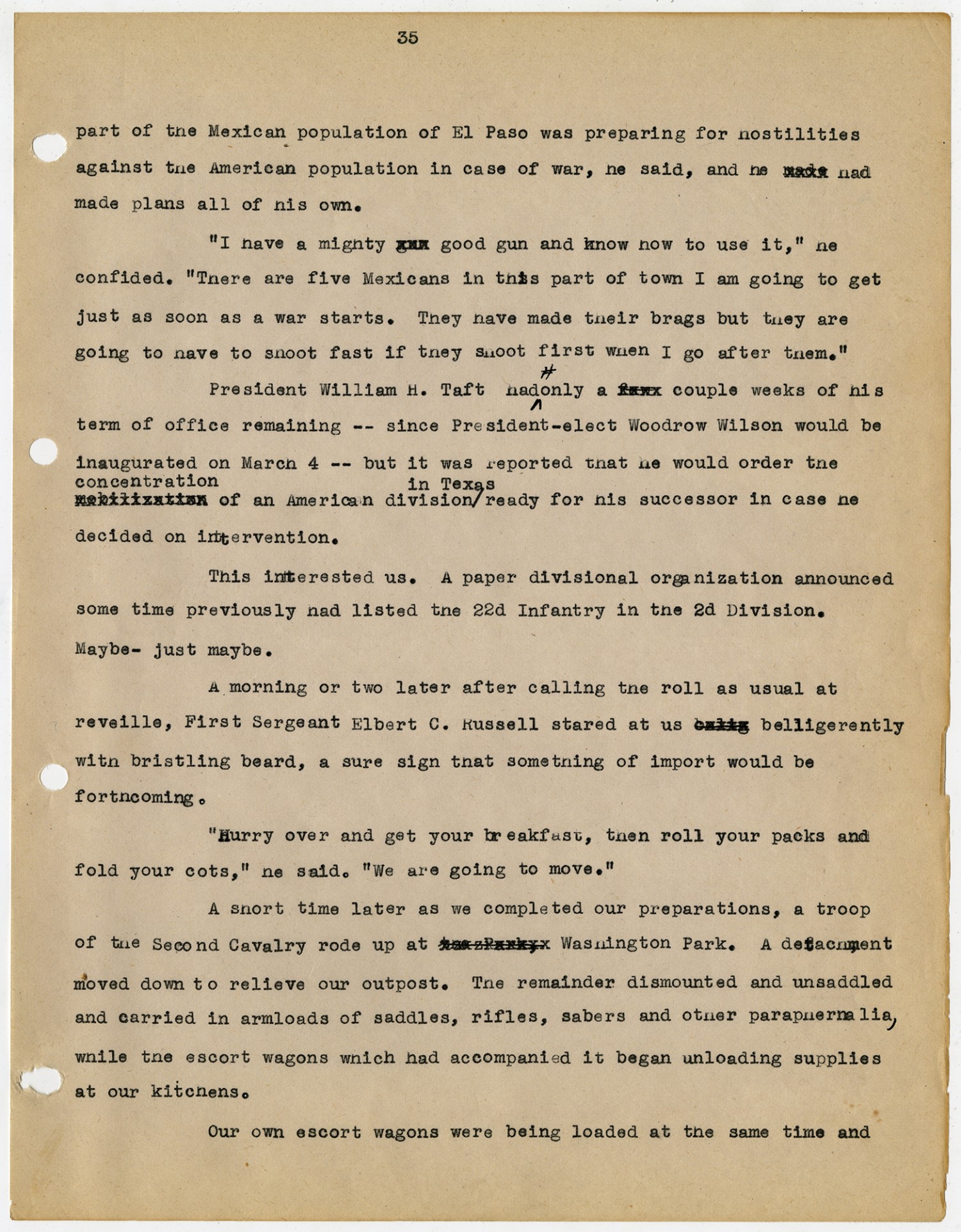

[photograph] NACO, ARI, [December] 1914. [photograph] U.S. INF. in Trench on Border Douglas, [Arizona. November] 4 [1915] [photograph] Chow Time US Soldiers in Trench on Border Douglas, [Arizona. November] 4 [1915]

Transcript

[photograph] Pvt Frank Zepp [photograph] Pvt Percy Long Co C, 22d Inf [photograph] James Mountcassal Sarver Rudisell Lynch Duncan Fullerton Wilcox Men of Co F, 22d US Inf Washington Park, El Paso [Texas] 1912

Transcript

[photograph] Our station Jefferson Barracks 1912 [photograph] Jefferson Barracks, [Missouri] 1912 [photograph] Billets, Co F, 22d US Inf, Washington Park, El Paso [Texas], December 1912

Transcript

[photograph] 1st Sgt EC Russell, 1912 [photograph] Pvt Aron Nikolonetski [photograph] Sgt Simenson Rodisill Samples Blubaugh

Transcript

National Geographic Society Dufaycolor by Luis Marden Here the Pecos, Flowing Across West Texas, Empties into the Rio Grand Cliffs form the United State frontier; lowlands at right are in Mexico. The tree-grown ridge at the cliff's base marks the pioneer roadbed of the Southern Pacific Lines, now relocated on the mesa above. In the Pecos's mouth stands a ruined bridge pier over which once rumbled California trains.

Transcript

Photograph by Luis Marden This Dizzy-Looking, Spindle-Legged Bridge Spans the Pecos River Above Its Confluence with the Rio Grande The Pecos, rising in northeast New Mexico, flows southeast across west Texas, to form one of the Rio Grande's chief tributaries. here Southern Pacific trains cross the rock-walled canyon on their long runs between New Orleans and California (Plate III and page 439). National Geographic [October] 1939.

Transcript

[page 37] After a period of freezing and waiting, we found our tourist cars, when they finally arrived, most warm and comfortable, and as I lay in my upper berth that night as the train jolted and jerked southeastward on the Texas Pacific railway I felt like one transferred from a bleak, freezing inferno to a comparative paradise. Off to the wars! Altogether I was in a most happy frame of mind -- possibly because I had never yet seen war. Morning found us near Alpine at the top of the Big Bend country, traversing a rugged region greener than that around El Paso and to me new and delighful. At the stations where we paused we found the cowboys and other loungers who greeted us as expectant of war as were we, and obviously, as men of the exposed frontier, expecting to be concerned in it, and in the case of the young men at least apparently looking forward to it with some relish. Marathon, which the young Mexican Maderista volunteer who had once guided me about Juarez had told me was his home; Sanderson -- Langtry. Much publicized as Judge Roy Bean has been in the intervening years, I had never up to that time heard of him. But an old corporal who had served many years on the border told me some of the anecdotes concerning him and pointed out the sign on the front of a building facing the tracks: "Justice of the Peace. Law West of the Pecos." And he further told me that the railway bridge over the Pecos canyon was the highest above the stream of any bridge then in the United States. We stared down with some awe at the water far beneath as the train crept across it. A detachment of cavalry -- the 14th if I remember right -- was stationed as guard at this bridge as well as at some other points along the railroad. Devils River and a coyote trotting across a hill and not afraid of a train. Del Rio, and a turn away from the border through

Transcript

[page 38] Spofford and to the east. Morning found us south of Houston in a region which appeared as southern as El Paso was western. The hut of the Mexican laborer had been replaced by the ramshackle shanties of the southern Negro. Forests of pine trees with long streamers of Spanish moss appeared here and there; once in awhile there were large hayfields, and now and then pretty country houses, with climbing roses, all in bloom, clambering over the front veranda, seemed like pages out of some delightful southern novel. In the air, mingled with the odor of the pines, was the salt smell of the sea. Soon we ran out on a huge, green, floorlike plain and presently reached Texas City which, as it turned out, was to be our homes for many a month. At Texas City, Texas, on this February 28, 1913, everything was activity. The sidings were crowded with the trains of eight regiments, some just arriving. Some almost unloaded. Scores of escort wagons slushed through the mud, their splattered mule teams straining every muscle. Everywhere was seeming confusion, and displeasure at the weather which had turned rainy and the camping ground which under the circumstances seemed little better than a swamp. North of town on this flat, treeless, grassy plain, pyramidal tents were already beginning to rise. Soon ours joined them, our officers frowning at the ground, permitting gaps in the line so as to avoid as many low spots as possible and take full advantage of occasional mounds.

Transcript

[page 39] The 2nd Division, the only division assembled at that time, was of the old triangular type which preceded the "square" type of World War I days. There were three infantry brigades which by the paper organization of the day were supposed to have three regiments each. In fact one brigade -- the Fifth, which was concentrating at Galveston across the bay, had four regiments, the 4th, 7th, 19th, and 28th. This brigade was soon to be commanded by Brig. Gen. Frederick Funston though I have the impression that at first Col. Daniel Cornman of the 7th Infantry was in command. On the Texas City side was the Fourth brigade, commanded by Brig. Gen. Hunter Ligget consisting of the 23d, 26th and 27th Infantry regiments, and our own brigade, the Sixth, commanded by Brig. Gen. Clarence R. Edwards, which included the 11th, 18th and 22d. There was also the 6th Cavalry, the 4th Field Artillery -- a regiment of mountain guns -- and some odds and ends -- a battalion of engineers, a field hospital, an ambulance company, a signal corps company, a bakery unit and an airplane squadron. Regiments probably ran about 800 men each and the the total strength of the division on June 30 after a considerable number of recruits were received is listed as being 517 officers and 10,770 men. Major General William H. Carter, a medal-of-honor man from Indian-fighting days, was in command. He was quoted in the Texas State Topics as saying: "This is the largest concentration of a single command of regulars in the history of the army." It is possible, however, that he was misquoted. The so-called "maneuver division" at San Antonio in 1911 had an aggregate strength of 12,598 at one time, and the command that

Transcript

[page 40] Major General William R. Shafter took to Cuba for the Santiago campaign of 1898 aggregated 16,887 of whom fewer than 3,000 were volunteers. However it certainly was one of the three largest concentrations of regular army troops in American history up to that time and those of us who were included therein, took considerable pride in being members of such a force, supposing that very soon we would be on our way to Mexico. As for the armament of the day, the infantryman's weapons was the 1903 Springfield rifle and bayonet, except that each regiment had a regimental detachment of two Benet Mercier machine guns carried on pack mules. The cavalry, of course, had rifle, pistols, and savers-- the slightly-curved 1906 model -- and I think two Benet-Merciers on pack horses. The artillery was armed with 2.95 pack howitzers. The expectation of immediate war did not last long. When President Woodrow Wilson was inaugurated on March 4 it became quite clear that he had no ideas of intervention, and the soldiery at Texas City settled down dejectedly in the mud while the high command pondered a better-drained camp site. The camp site matter was a somewhat serious one in the Sixth brigade at least. Probably someone had made some sort of preliminary reconnaissance before we were assigned to the ground on which we had pitched our tents, but rather obviously that recommaissance had been made at some time in dry weather. Now it was raining more or less continuously and and there was no drainage. Ditching the tents did no goo. Diking was more appropriate but rain at night usually overflowed the dikes. In my tent we fastened our weapons and equipment onto the central tent pole and kept all else on our cots, At night we tied our shoes up on

Transcript

[page 41] onto the cots to keep them out of the couple of inches of water we could count on covering the dirt floor by morning. All tents were not this bad, or course, but on the other hand some were worse, and getting to the mess hall at the head of the company street meant wading two or three lakes. Meanwhile the engineers were busy working out the official solution to the problem on the beach a mile and a half to the east, staking out lines of proposed ditches -- about 17,000 feet to a regiment, someone said. Soon we were going out on working parties to this trench net-work and a little later the entire brigade floundered through the mud to the new site and re-pitched the camp. The engineers had figured well. Thanks to the ditches which drained onto the beach itself -- perhaps a fall of four or five feet at high tide -- the camp was livable and while at first the roads were quagmires they were soon gravelled and the place became excellent for its purpose. It was while on one of the working parties digging ditches that I first saw General Edwards who became well known a few years later as the World War I commander of the 26th Division. He and his staff were out riding horseback watching the work on his brigade area. As the general rode up we saw our Corporal chapman -- a lean, ramrod like soldier of Indian mien and perhaps 45 years of age -- come stiffly to attention and salute then to our surprise we saw the general lean over, shake hands cordially with him, and dismount and chat for awhile. "He used to be my company commander," was to corporal's complete explanation in response to a query as we trudged back to camp. The episode gave me a good opinion of generals in general which I have never had any occasion to lose. It was maybe 8 or ten months later that I had my own first and only conversation with General

Transcript