Harold I. Magoun Sr. Memoir - 1917-1919

Transcript

"Over There" - 1917 - 1919 Harold I Magoun, Sr When Maggie was a little boy he never did like liver. The corner grocer gave it to him for the dog. So when he enlisted years later and arrived in camp in the middle of the night, and was offered cold, leftover liver, generously sprinkled with windblown dust, he did not think he was going to like army chow either. He had joined one of the two Boston ambulance units recruited under the auspices of the Harvard Medical School for detached service with the French Army. He was told to stay in college until called. This was a stroke of luck. Right in the middle of final examinations the call came, excusing him from the two he expected to flunk. The Harvard faculty passed him anyway. The Fair Grounds in Allentown, Pennsylvania, was the site chosen to train the many groups who came there, recruited from all over the country. His outfit, United States Army Ambulance Service # 544, later in France known as SSU 544, was quartered in the race track grandstand, with cots on the treads from which seats had been removed. This provided plenty of fresh air but no privacy. Facilities were never adequate for the units arriving daily and complications did not help any such as the night visit of a skunk in Building 7, when some of the city lads resented the intrusion. They were issued new uniforms the next day. And then there was the broken water main at night in the former display area beneath the grandstand which was now the mess hall. It was a mess, all right, deluged with sewage. Yes, Maggie was one of the cleanup squad. It had to be done before breakfast. Hot weather generated violent thunder storms which threatened the flimsy tent-roofed Y.M.C.A. quarters. Obie got the nod to climb up on top and hold down the canvas in the wind and rain. He was one service man with dampened ardor! Maggie was picked to be the bugler for Section 544. That saved him from some strenuous projects but made others worse such as trying to blow a marching tune while hiking on a sweltering hot day carrying a loaded haversack. But he enjoyed playing "Retreat" when the flag was lowered and "saying good night" to the folks at home as he put his heart and soul into "Taps" when all the lights went out.

Transcript

[page 2] Easing the congestion which continued to grow in the Fair Grounds led the officers to grasp at any solution. One was a truck ride to New York for several sections and a parade down Fifth Ave. The convoy had stopped in a little town named German Valley for a cold lunch and the townspeople, learning when the return would occur, showed their patriotism with a tremendous spread of all kinds of good food on the Village Green. And there was another dusty ride to Washington, D.C., where the outfit was secluded at Fort Meyer with prunes and "canned woolly" for Thanksgiving dinner, despite the invitations which The Y.M.C.A. had obtained in town. The next day the lads were in a bad humor for the parade, this time past the old War Department. The lieutenant got confused, ordered "squads east" instead of "squads west" and the boys cheerfully obeyed, stomping right up on the lawn and over the flower beds. The unit got a new commanding officer shortly afterwards. When cold weather arrived we were trucked out to an area of surface mining and told to dig in. Eight of us excavated our new residence, raised the side with sods, formed a supposedly watertight roof with our pup tent shelter halves and built an upper and lower berth with corn stalks as a mattress. The real accomplishment was tunnelling up through the ground at the back for a fireplace. We were so warm and comfortable on those cold nights that the officers often came down to spend the evening -- too warm the night the corn stalks caught fire. We called this the "Guth Country Club." The days were spent in drilling and practice in caring for the "wounded". One slacker always wanted to be the victim so he could take it easy. We were hard-hearted enough to insist that, with "both legs shot off", he had to get up and walk to the first aid station. These exercises often lasted so long that we had to eat in the dark. Maggie got in hot water the night he mistakenly washed his mess kit in the officers' coffee. They did not realise it but he probably improved the taste of the coffee by so doing. When Christmas came most of the section enjoyed 5-day leave. But Maggie and his new found buddy, Hugh, had to hold down the quarters we were then occupying in zero weather -- the hay loft over the racing stables with inch cracks between the boards to condition the hay. Yes, we had a stove but no stove pipe so we just put on more clothes to go to bed on our cots.

Transcript

[page 3] Then Hugh came down with the flu! Maggie wasn't much of a nurse and Christmas Eve was far from ideal but the patient recovered. On January 8th we left for overseas. Our ship was [RMS Carmania] of the Cunard Line, converted into a troop carrier with three tiered bunks down in the stearage. The heat, foul air and crowding was hardly conducive to sleep. But it was very cold on deck as we watched the lights of Long Island fade away. Morning saw us in Halifax Harbor, joining the convoy for the trip across. The city was in ruins from the explosion when the Belgian Relief Ship accidentally rammed the French munitions ship [SS Mont-Blanc]. Maggie drew guard duty on the top deck where the frigid wind was worst. He did his best to keep his blood circulating by all sorts of gyrations. He needed to with the harbor water freezing over from the cold. But one of the "60-day wonders", who was Officer of the Day, bawled him out unmercifully and made him stand at attention and recite the Articles of War including the phrase: "To walk my post in a military manner", etc. Before this was over Maggie was so hot under the collar that the cold did not matter. When he was relieved he decided on a hot shower, not knowing that it was salt water, which requires a special type of soap. So he really had a nice mess to get out of his hair. And then there were maggots in the food. Setting-up exercises on the pitching deck after we sailed called for ballet dancing technic. If he did a squat as the ship rose it was like walking up hill. When he straightened up as the boat went down again he just about took off. After ten days, most of the time towards the North Pole, the convoy struck the Gulf Stream and things warmed up considerably. Liverpool, at dawn, with a nurse waving from the window of a dock-side hospital, called for a cheer that woke the echoes. SSU 544 always was a noisy bunch. The army rations of canned hash, beans, cheese, hardtack and even "canned woolly", issued for the train ride to Winchester, plus the green countryside and the sunshine quickly dispelled the shortcomings of the voyage. The Morn Hill Camp, just outside the city limits, was a well run staging area with strictest economy of food, electricity and everything else. The evening meal was at four o'clock before it got dark and consisted of one

Transcript

[page 4] slice of bread, some cheese, jam and tea. Before retiring on our wooden pallets we were hungry again and so patronized the canteen liberally. We were allowed in town only in formation. The cathedral was the center of attraction. Beside it stood a tombstone with this inscription: Here sleeps in peace a Hampshire Grenadier Who caught his death by drinking cold, small beer. Soldiers be warned from his untimely fall And whenever hot drink strong or none at all. The interior of the cathedral was lined with memorials to fallen soldiers, mortuary boxes of Saxon and Danish rulers and statues of heroic leaders. We were particularly amused by the oaken seat bottoms of the choir chairs, designed to spill the sleepy brother at a midnight service, who did not sit far back and erect. We noticed the organ playing softly but suddenly it burst forth with all the stops open playing "The Star Spangled Banner." We all snapped to "attention", quite overwhelmed with the age of the cathedral, and its place in history as the cradle of English royalty for so many years, paying such a tribute to us who had come to help defend our mother country. The trip to Le Havre, France, during a stormy night was not long. On arrival we were told not to undo our packs lest we acquire "cooties" and we were issued fumigated blankets for the night. We slept in round squad tents like the spokes of a wheel, with our clothes on. This did not allow for big American shoes. Several days later it became apparent that we had not only nourished cooties in the supposedly clean blankets loaned to us but also succeeded in making generous transplants to our own belongings. This was all the more discomforting during the two nights and one day we spent travelling in a French box car, supposed to carry only 32 men while we were 47. The seemingly one square wheel did not help either. Thus St. Nazaire, with its rain and mud, was a welcome change when we finally arrived. We got rid of the cooties by putting all our clothes and blankets through the "incinerator", so called. Part of the crew assembled ambulances from big shipping cases while the rest of us worked on the roads. The spirit of SSU 544 rose to the occasion after the first mail arrived from home. A hastily formed minstrel show was cordially received in several parts of the huge encampment. Maggie did his last service as a bugler. He put his soul into the nighttime blowing of "Tattoo", "Call to Quarters" and lastly

Transcript

[page 5] "Taps", facing the west and blowing a loving "good night" to the folks at home. And then a puppy howled! When all our ambulances were assembled we left in a convoy. Hugh and Maggie drove one car loaded with a drum of gasoline, 3 barracks bags, a generous assortment of spare parts and our bedding. Somehow we slept on top of all this but it was not easy, as we stopped each night enroute to Paris. The mechanics brought up the rear in their truck to take care of breakdowns but the worst trouble was with hobnails on the road puncturing the tires. We became expert at tube patching but it was not easy in the snow and cold. In Paris we painted the black running gear, wheels and hood a somber green to match the car body. We had several days to visit some of the main attractions in this beautiful city. The Louvre Museum was closed for the war but Le Grande Magasin de Louvre, a large department store, proved interesting -- too much so as we ascended one escalator after another, only to be requested to go back down as this floor was exclusively for "madame et mademoiselle". Most memorable of all was Notre Dame Cathedral in all its grandure -- and all its pathos. In a small side niche where the candles were burning knelt a fair young widow praying for relief of her aching heart. Little did we realize that months later we would see the same thing in the German cathedral of Speyer am Rhine, reducing all the "blood, sweat and tears" of war to a common denominator. On the way to the front near Reims we stopped for the night at Meaux. a quiet little village where the tide of the German drive on Paris was stopped by General [Joseph] Joffre's Territorials, rushed to the front by taxicab. We had hardly settled for the night when a stream of soldier laden trucks poured by for hours. We later learned that the collapse of Russia enabled Germany to stage an attack "to end the war", creating a gap between the British and French troops. Three French divisions were rushed up and held against the Germans. Being "at the front" meant having our sleeping quarters when not on duty in a deserted village a little way back and taking turns at three-day shifts at the Poste de Secours or First Aid Station back of the trenches to which the wounded were brought on stretchers. From this, night or day we evacuated the wounded to the Field Hospital. Other members of our group

Transcript

[page 6] then took the seriously wounded to Surgical Field Hospitals further in the rear. The Germans were well ensconced on a hill, Nogent L’Abbesse, with captive balloons and an observer to report any vehicles crossing the broad plain we had to travel. It made no difference that our ambulances were well marked with red crosses. We were “fair game” for a battery of “77’s”. They would guess our speed and plant three shells along the road, trying to make a hit. But we altered our speed, slowing up and then spurting, so that it almost got to be a game. And we won, most of the time. Zed was called the luckiest man in the section because his ambulance was pierced with 97 pieces of shrapnel and three tires were ruined but he was unharmed. In the night it was very different. That was when the raids for prisoners occurred with a deafening roar of artillery and machine guns, shells landing along our route as we tried to find our way in the darkness without headlights, over impossible roads and carrying mortally wounded men who cried out in agony. We became accustomed to the danger but never to the screams of pain. Night driving was a bit easier with a cloudless sky because we could be guided in some areas by the pathway of stars overhead between the tall trees that lined the road. But many nights even this was fogged out. On one unforgettable trip we suddenly collided with an immense two wheeled ammunition wagon drawn by two horses, hitting it hard enough, with the horses rearing, to turn it on its side and snarl the team in a mess of harness. That took a while to untangle. But the steering gear of the Ford was bent so that it made driving almost impossible, especially with a skull-fractured individual to evacuate. Presently, as we crept along, there was a tremendous bump, a clash of metal as though the whole car had come apart and then an abrupt halt. We got out in several inches of water to investigate and found the differential casing slid up on a large building block from a shelled house. It necessitated jacking the car up, working the stone out of the mud, and lowering the jack so we could start again, the poor poilu inside prodding us with agonizing groans. The city of Reims was about 15 kilometers from our base. Night after night the Cathedral was lit up with the murky yellow smoke of the incendiary bombs and the burning buildings. We marvelled at the way the beautiful ed-

Transcript

[page 7] ifice survived the barrage. Stained glass windows had been removed but the stone walls were badly pitted. Trenches ran right thru the city, most of which remained in the hands of the gallant 3rd French Colonials to which regiment we were attached. We ate with them on post. They were adept at varying the menu with delicious snails from nearby trees or a chunk of horse meat from a dead artillery team, well spiked with garlic -- a gastronomic treat! Coming back from three days on the first aid post Maggie found a platoon of Senegalese troops in the village -- great, tall chaps as black as coal and with slashed cheeks which apparently was a mark of distinction with them. They carried no weapons except “coup coups”, large cleavers which they used with such effectiveness, indistinguishable in the darkness, that the Germans were much afraid of them. Maggie was afraid of them as well. As he parked his ambulance two of them approached with cigarette lighters, seeking gasoline to fill them. He turned to comply but when he turned back there were six of them, each with an empty champagne bottle. He was just about to offer them the car too when the sergeant of SSU 544 saw what was happening and stepped into the breach. Words were unavailing but he had a happy thought. He pulled out his false teeth and held them up to the group. The poor ignorant black boys forgot all about gasoline and tried their best to pull their own teeth out but without success. The day was saved. On June 18th there was a direct attempt to carry the defenses of the city of Reims by storm but this failed with bloody losses. So General [Erich] Ludendorff planned the next attack to strike in from either flank and so capture this strong point. A tremendous barrage of both gas and explosives sprang up towards Epernay on the left and Chalons on the right. All the ambulances were more than busy. A wonderful example of faithful and unswerving devotion to duty appeared in the way the old Priest hastened to the center of action, le fort de la Pompelle, when the action started. Over the top with his walking stick and souls passing in peace! This attack too failed but there were many wounded to evacuate. And many who were gassed died because there was no remedy. In the the lull following this action we indulged in singing in the evening.

Transcript

[page 8] Section 544 was noted for this. After what we had been through with some ambulances smashed, some gas inhaled but no severe casualties in our ranks, Leon started with a hymn. Much to the surprise of some of us most every one joined in. What a touch of home! We sang on and on -- all the dear, old tunes, often without words but we put our whole souls into them. It was past eleven before we queted down. Oh yes and we celebrated July 4th as well as Bastille Day with proper concern for those two occasions, in so far as duty allowed. Of course some of the lads were hardly fit for duty as the day wore on. But we filled in. July marked the turning point of World War I. Stung by previous failures [Erich] Ludendorff launched 52 divisions against the 4th French Army east of Reims, his objective the Marne River between Epernay and Chalons. This, he hoped, would open the eastern side of the redoutable Montagne de Reims. West of the city he hurled 30 divisions against the line between Reims and Chateau Thierry. But Fate was against him. The U.S. Marines and the brave poilus held that front and even forced a retreat of six miles. Being right in the middle, SSU 544 was really in a hot spot. We were told to pack up, carry our barracks bags to the mudguards of our cars and be ready to leave at any time. But we had no thought of that because of the wounded to be evacuated. The 3rd Colonials had made a lucky raid and captured 127 Germans from whom it was learned that this attack was to be on July 18th at 1:00 am. A few brave machine gunners were left in the front lines but all the rest of the troops were moved back two or three miles to strong positions at the base of the elevation called the Montagne de Reims. So the German barrage fell on empty trenches. And then the French artillery cut loose on the massed Germans who were advancing over the deserted area. It was a massacre. And a long line of prisoners. We evacuated many German wounded, along with the French. On July 15th the Germans had been sure that this “peace storm” would win the war. On July 18th they were sure they would lose the war. And there were none of them south of the Marne River except for the prisoners. “You will be French as a result of today” an Alsatian soldier was told by his German comrades as they retreated to the Vesle River.

Transcript

[page 9] Quite a few members of SSU 544 were decorated with the Croix de Guerre for bravery in evacuating the wounded under fire. They had no thought but to do their best, night or day. Many suffered from eye and throat irritation from the poison gas. Horace’s car was ditched by a shell and he barely escaped with his life. Charlie the same. Making eighteen to twenty trips in twenty four hours and carrying out about a hundred wounded or gassed soldiers during that time was routine. We sometimes went three weeks without taking off our clothes because of the urgency of the times and the necessity of snatching an hour’s sleep here and there, while still being ready for instant duty. And the darned cooties loved that! We seemed to lead charmed lives when it came to shell fire. Maggie’s car stalled one day in plain view of the captive balloon on Nogent L’Abessee. A relief car came to find the trouble. Shell fire soon began. Maggie ducked behind a tree but the shell exploded behind it also. He was not wounded. After the car was started he drove into the village around a corner for which the German gunners had the exact range. A shell exploded as he made the turn, not ten feet away but the other side of a stone wall. He was deluged with dust, debris and fumes but continued on unscathed. And so it went day after day. No wonder we rejoiced when a French aviator was able to set the balloon on fire, as often occurred. Meanwhile clothes were wearing out and there was no replacement. Zed had a trip to Epernay with wounded one day and visited the Quartermaster Department, hoping to get a new pair of pants. He was refused for not having the proper requisition papers. With his usual lack of respect for authority he said: “Hey Lieut. Look!” And he turned his back and bent over showing a large portion of his “posterior” (derriere in French). He got the pants. Maggie had a similar problem on a smaller scale and had the brilliant idea of patching his trousers with adhesive tape. The only trouble was it stuck to his skin more than to the cloth. In desperation the Germans began a propaganda barrage. Planes dropped a sheet entitled: “The Better Part of Valor”, which suggested in no uncertain terms that “fighting in France for England” was really cowardly and that if were brave we would save our lives by deserting. That was a laugh

Transcript

[page 10] Through all this time the Y.M.C.A. was the only organization we saw at the front. It came occasionally with writing paper, reading matter, cigarettes and other gifts. Once during a lull at the front the “Y man” came and with him was a beautiful American girl from the “Y” at Chalons, the only one we had seen in months. Words can never express what that meant to us. Miss Seeber’s coming was a glimpse of home and loved ones which we needed so much. We bless her memory. After many strenuous weeks it was time for SSU 544 to have a short rest. We were relieved by another section and took up temporary residence in a board and tar-paper barrack near an air field, a few miles back of the lines. It was a bright night with a full moon. Some of the lads were celebrating a bit, the lights were all on and the windows open so that the light showed. Suddenly we heard the alternating rhythm of a German plane. Then there was a definite hiss like that of a high speed vehicle. The bomb burst not far away. The celebrants sobbered up instantaneously. The plane came closer and seemed directly overhead. We heard another bomb falling. What does one think at a time like this? “Father into Thy hands I commend my spirit.” When the rest was over we went back into action following the retreating Germans into an area they had occupied for four full years. It was a barren sight with houses burned, bridges blown up, roads mined and trees cut down. We carried many wounded, jolting them over the shell torn roads, the almost impossible pontoon bridges with a steep down dip and a climb on the other side because of the river banks. We were right in the midst of the action with troops advancing in open formation, batteries firing madly, cavalry on beautiful Arabian horses dashing from one bit of cover to another to keep in touch with the retreat. The Germans were throwing everything they had at the advancing French. One of the lads later described it in verse: As a kid I listened to preaching of the terrible wages of sin, Of the Hell of the dammed, a terrible place that Satan put sinners in. But man if you’d been up at Blanzy, that town near the bridge o’er the Aisne Where the Heines cut loose with all sorts of abuse and the shells dropped around you like rain - Where you list’d to the cry of a dying guy, plumb out of his nut with pain, Where the river ran red with blood that was bled that justice and right mightn’t die -- Death might be your fate as you fired with hate but, hell, you wasn’t much loss. Of the bunch that went in not many came back. They are there with a white wooden cross.

Transcript

[page 11] If you’re one of the guys that went and came out of that terrible din You can laugh at the preacher who scared you and go to Hell with a grin. We were waiting for the barrage to lift in an underground shelter, knowing that some of us who went out might not come back alive. And then the most profane and seemingly atheistic guy in the outfit spoke up and said: “Maggie would you say a prayer for us?” We needed it. The First Aid Station was crowded with wounded. The retreating Germans had the exact range on the corner where the road turned back towards Reims. They were firing a shell at that corner every three minutes. We had to load an ambulance and be ready a short distance away, dash to the corner and get around it between shots. More then one wounded man crawled back out of the ambulance when it was loaded. They had had enough. One of our group, who had been with us only a month, died with a shell fragment through his head. Along with all the high explosives there was chlorine, phosgene, mustard and tear gas coming our way. With fogged gas masks we could not see to drive so we had to take them off. Quite a number of the section were affected, seven seriously. Maggie was blind and could not speak above a whisper for nearly six weeks but stayed with the outfit because the hospitals were choked with worse cases. Condensed milk was all he could swallow. Besides that, we were pulled out of action and sent south into the border of Alsace Lorraine, pending a tremendous drive in that area. But the armistice changed all that and how we celebrated! The jokers kept saying: “Maggie! Quit making so much noise!” With peace finally a fact there was time for the amenities. The Medecin Chef stated: “I want to pay homage to the drivers of SSU 544, whose physical endurance, constant evenness of temper and quiet courage has been absolutely wonderful.” And the French Colonel added: “I absolutely approve the homage given the American drivers, who have shown, under all circumstances, and at all times when there was much danger, the most absolute abnegation and the most sincere devotion to the cause.” But the Boston Transcript really capped the climax. Its headlines read: “EVERY MAN DECORATED. Record of Boston unit in French Army unequalled. Lynn boy has four citations for bravery.” Well maybe!

Transcript

[page 12] Danny Mack had gone through it all without a scratch. But he fortified himself so much for the victory parade in Boston that he became a casualty - he fell down in front of the grandstand and broke his leg. Old ambulance drivers never die. They just run out of gas.

Details

| Title | Harold I. Magoun Sr. Memoir - 1917-1919 |

| Creator | Magoun, Harold I. Sr. |

| Source | Magoun, Harold. Harold I Sr. Magoun Memoir. 1917-1919. Harold I. Magoun, Sr. Collection. 2008.80.02. Museum of Osteopathic Medicine, Kirksville, Missouri. |

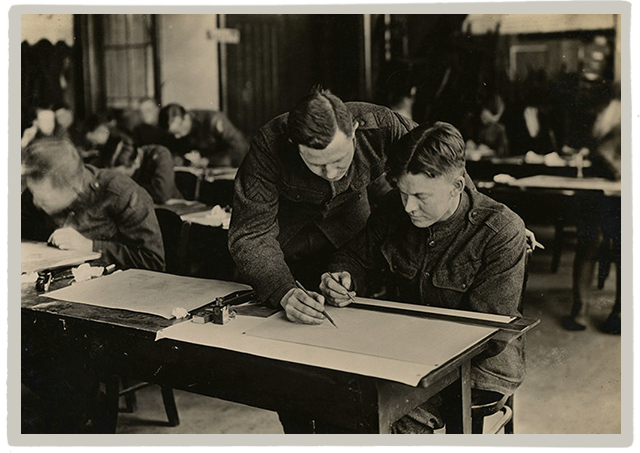

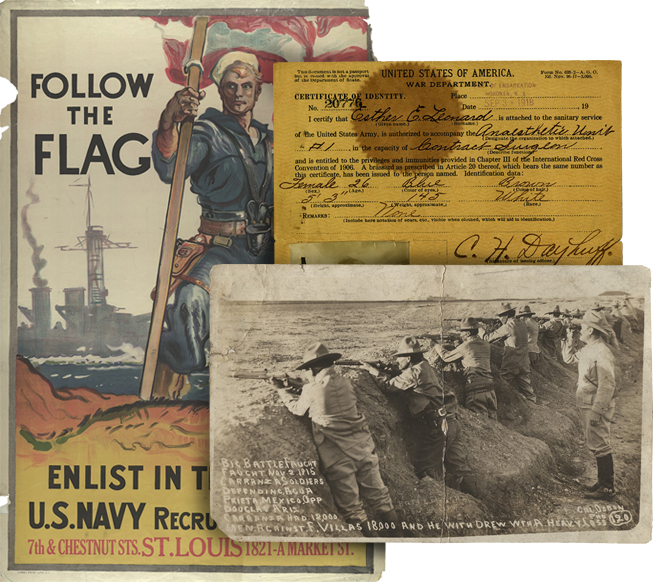

| Description | Harold I. Magoun, Sr. wrote this memoir about his experiences as an ambulance driver during World War I. Magoun was a part of the American Field Service #544, which in turn served as a detachment in the French Army. In this personal account Magoun described his various experiences throughout the war, specifically his time spent driving away wounded soldiers from the Western Front. Later in life, Magoun moved to Kirksville, Missouri and attended school at the American School of Osteopathy (now A.T. Still University). |

| Subject LCSH | World War, 1914-1918--Medical care--United States; World War, 1914-1918--War work--Y.M.C.A.; Singing; Military uniforms; World War, 1914-1918--Chemical warfare; World War, 1914-1918--Casualties; World War, 1914-1918--Hospitals |

| Subject Local | WWI; World War I; SSU #544; American Field Service; Ambulance Service; RMS Carmania; SS Mont-Blanc; Gas mask |

| Site Accession Number | 2008.80.02 |

| Contributing Institution | Museum of Osteopathic Medicine |

| Copy Request | Requests for permission to publish or reproduce material should be directed to the Curator, Museum of Osteopathic Medicine, 800 West Jefferson Street, Kirksville, MO 63501; telephone 660-626-2359. |

| Rights | The text and images contained in this collection are intended for research and educational use only. The Museum of Osteopathic Medicine does not claim to hold the copyright for all material; it is the responsibility of the researcher to identify and satisfy the holders of other copyrights. |

| Date Original | 1917-1918 |

| Language | English |