Rudolph Forderhase Memoir - September 21, 1917 - January 12, 1918

Transcript

WE MADE THE WORLD SAFE!! ? ? ? Camp Funston 21st of [September] to 12th of [January] 1918 Book One

Transcript

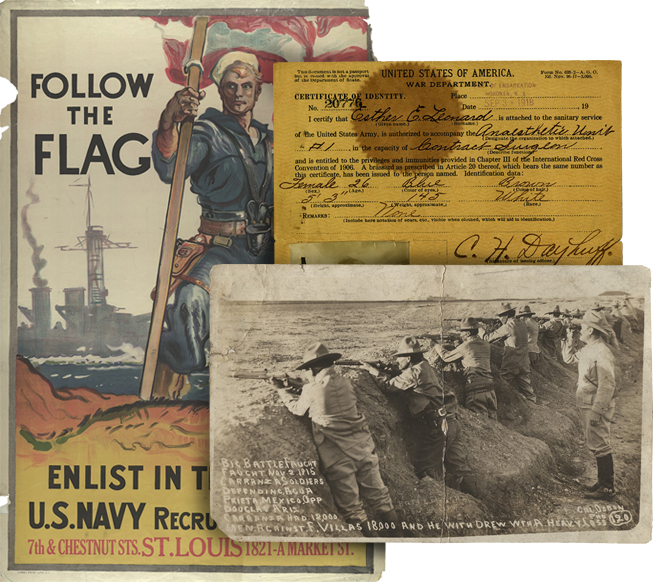

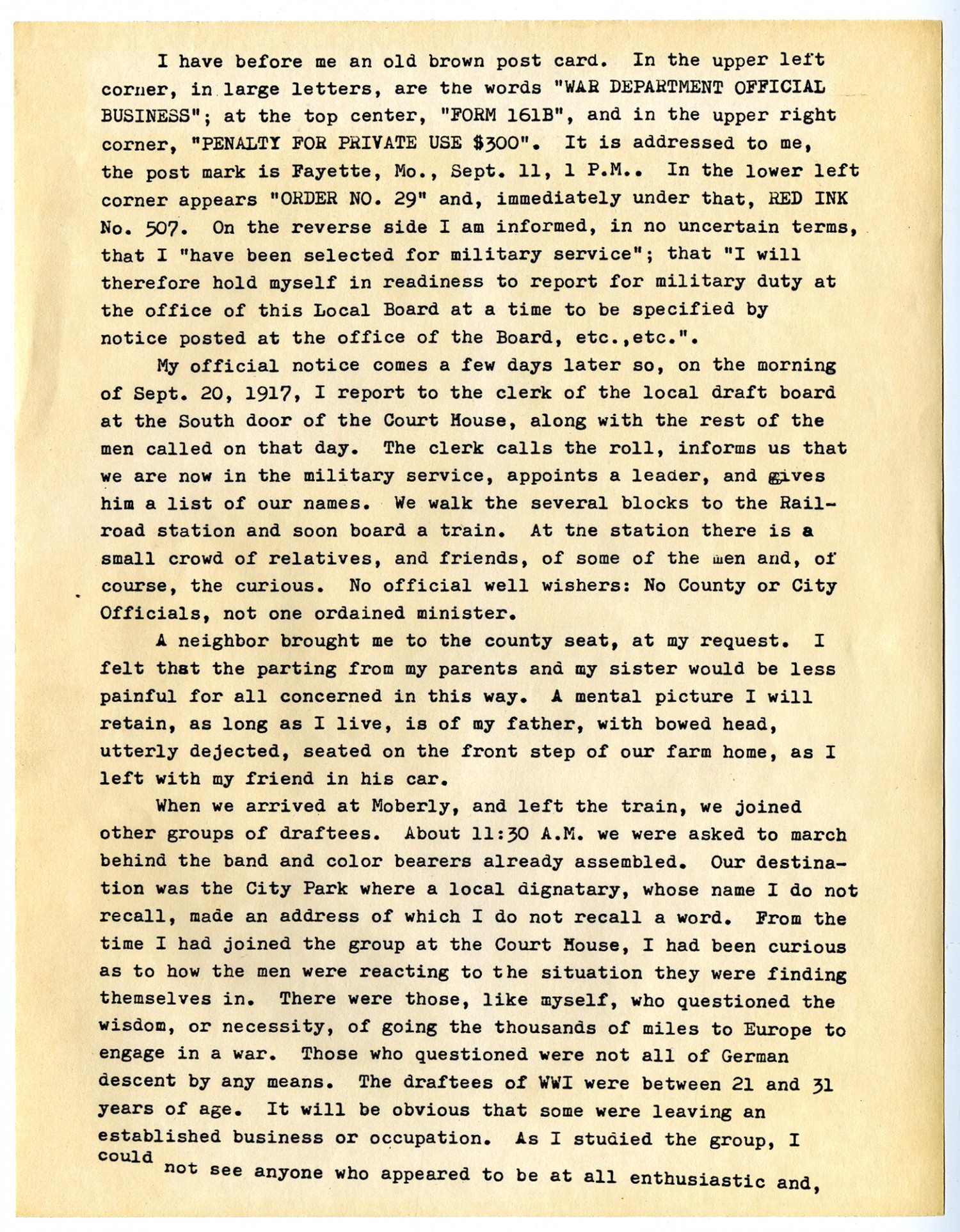

I have before me an old brown post card. In the upper left corner, in large letters, are the words "WAR DEPARTMENT OFFICIAL BUSINESS"; at the top center, "FORM 161B", and in the upper right corner, "PENALTY FOR PRIVATE USE $300". It is addressed to me, the post mark is Fayette, [Missouri], [September] 11, 1 P.M.. In the lower left corner appears "ORDER NO. 29" and, immediately under that, RED INK No. 507. On the reverse side I am informed, in no uncertain terms, that I "have been selected for military service"; that "I will therefore hold myself in readiness to report for military duty at the office of this Local Board at a time to be specified by notice posted at the office of the Board, etc., etc.". My official notice comes a few days later so, on the morning of [September] 20, 1917, I report to the clerk of the local draft board at the South door of the Court House, along with the rest of the men called on that day. The clerk calls the roll, informs us that we are now in the military service, appoints a leader, and gives him a list of our names. We walk the several blocks to the Railroad station and soon board a train. At the station there is a small crowd of relatives, and friends, of some of the men and, of course, the curious. No official well wishers: No County or City Officials, not one ordained minister. A neighbor brought me to the county seat, at my request. I felt that the parting from my parents and my sister would be less painful for all concerned in this way. A mental picture I will retain, as long as I live, is of my father, with bowed head, utterly dejected, seated on the front step of our farm home, as I left with my friend in his car. When we arrived at Moberly, and left the train, we joined other groups of draftees. About 11:30 A.M. we were asked to march behind the band and color bearers already assembled. Our destination was the City Park where a local dignitary, whose name I do not recall, made an address of which I do not recall a word. From the time I had joined the group at the Court House, I had been curious as to how the men were reacting to the situation they were finding themselves in. There were those, like myself, who questioned the wisdom, or necessity, of going the thousands of miles to Europe to engage in war. Those who questioned were not all of German descent by any means. The draftees of WWI were between 21 and 31 years of age. It will be obvious that some were leaving an established business or occupation. As I studied the group, I could not see anyone who appeared to be at all enthusiastic and,

Transcript

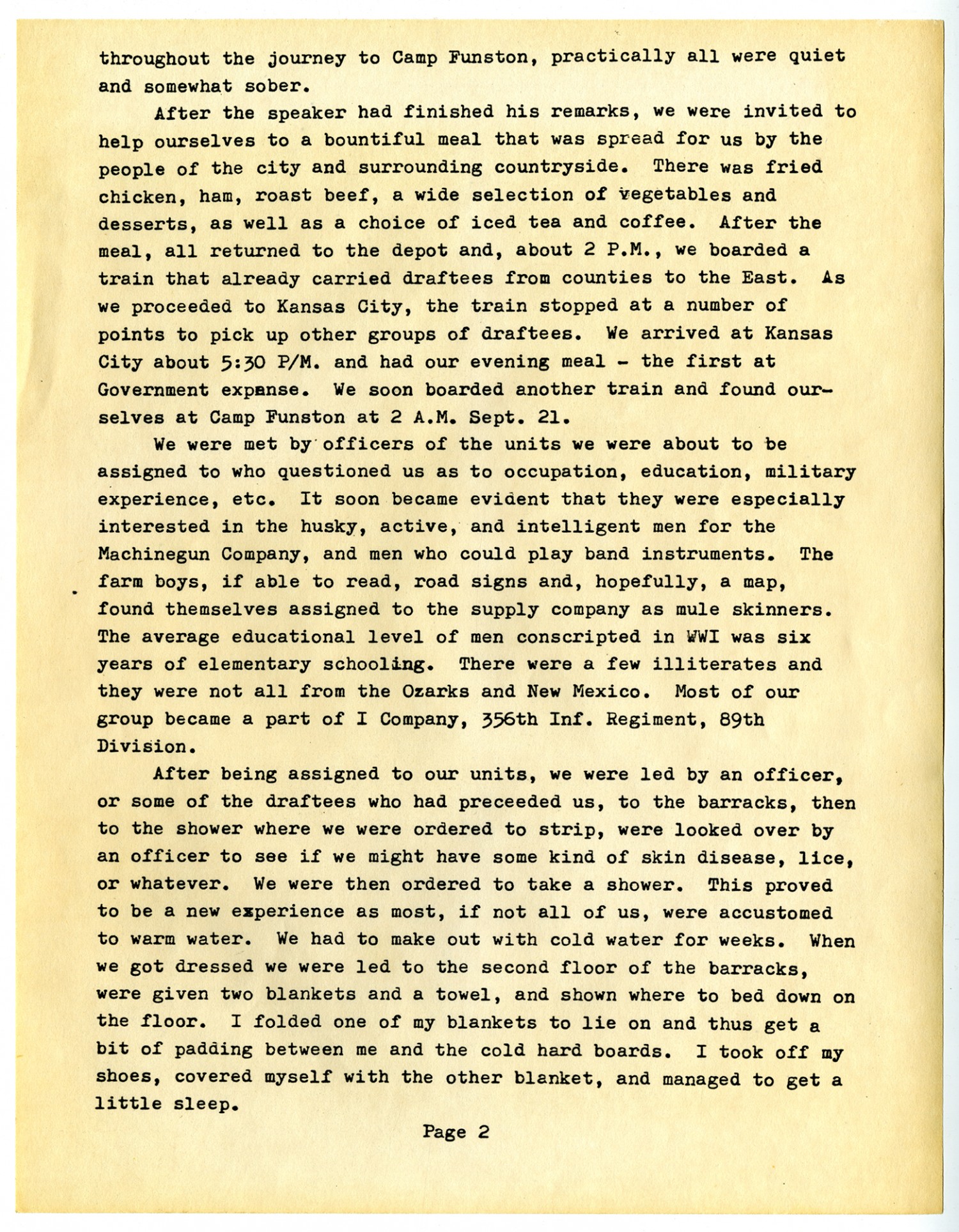

throughout the journey to Camp Funston, practically all were quiet and somewhat sober. After the speaker had finished his remarks, we were invited to help ourselves to a bountiful meal that was spread for us by the people of the city and surrounding countryside. There was fried chicken, ham, roast beef, a wide selection of vegetables and desserts, as well as a choice of iced tea and coffee. After the meal, all returned to the depot and, about 2 P.M., we boarded a train that already carried draftees from counties to the East. As we proceeded to Kansas City, the train stopped at a number of points to pick up other groups of draftees. We arrived at Kansas City about 5:30 P/M. and had our evening meal - the first at Government expense. We soon boarded another train and found ourselves at Camp Funston at 2 A.M. [September] 21. We were met by officers of the units we were about to be assigned to who questioned us as to occupation, education, military experience, etc. It soon became evident that they were especially interested in the husky, active, and intelligent men for the Machinegun Company, and men who could play band instruments. The farm boys, if able to read, road signs and, hopefully, a map, found themselves assigned to the supply company as mule skinners. The average educational level of men conscripted in WWI was six years of elementary schooling. There were a few illiterates and they were not all from the Ozarks and New Mexico. Most of our group became a part of I company, 356th [Infantry] Regiment, 89th Division. After being assigned to our units, we were led by an officer, or some of the draftees who had preceeded us, to the barracks, then to the shower where we were ordered to strip, were looked over by an officer to see if we might have some kind of skin disease, lice, or whatever. We were then ordered to take a shower. This proved to be a new experience as most, if not all of us, were accustomed to warm water. We had to make out with cold water for weeks. When we got dressed we were led to the second floor of the barracks, were given two blankets and a towel, and shown where to bed down on the floor. I folded one of my blankets to lie on and thus get a bit of padding between me and the cold boards. I took off my shoes, covered myself with the other blanket, and managed to get a little sleep. Page 2

Transcript

We were aroused at 6 A.M. to experience the most hectic Sunday that probably any of us had ever experienced. We were told to get shaved and be ready for breakfast at 6:30. As we entered the mess hall, we were issued a messkit and canteen cup and were given a demonstration in their use. The food we were offered did nothing to raise our spirits. This was true of the food we were to receive for some time to come. Few men had acquired any experience as cooks. Good eating places were not readily found, except in the larger towns and cities. We had one man who had some experience as a cook. Our Mess Sergeant was another. Some of the men wanted to be cooks in order to get out of drill and, hopefully, keep out of combat. The Mess Sergeant was one N.C.O. I did not envy. It was his duty to order the food. He was allowed thirty to thirty-three cents per man, per day, to purchase the food we ate. It may surprise the reader that it did not require this much all of the time and the mess fund increased to the point that, when we were in the Army of Occupation, our Mess Sergeant was able to provide us with a few welcome extras. After breakfast, the task of making soldiers out of us began at once. The Articles of War (duties of a soldier and penalties for disobedience, etc.) were read to us. We were instructed in military courtesy, how to recognize the rank of the officers and non-commissioned officers, suggestions on health care and cleanliness. A truck unloads steel cots and we carry these into the barracks. We get vaccinations for smallpox and antithpoid injections. When not engaged in any of the above activities, we are given instructions in the "school of the soldier" (how to properly stand at attention, do an about face, left face and right face). On October 3rd another group of 85 men arrives. A man from Northwest Missouri arrived in camp wearing a tan uniform that had been given him by a veteran of the Spanish-American war, who seemingly wanted to do something to alleviate the publicized shortage of uniforms. Issuing us such parts of the uniform as were on hand, also began on that hectic Sunday. One of the first to get his O.D. shirt, and breeches, was our comrade with the tan canvas uniform. A week later I find I am now outfitted with a shirt, breeches, belt, shoes, hat, and leggin's; also a long overcoat (which I am not Page 3

Transcript

permitted to wear in formation). I am issued a blouse (army for coat), on October 17. Also in the meantime we have each acquired a bedsack. Upon being issued this, we were told to take it to the supply dump where we could fill it to our own specifications with wheat straw. Also, on this second Sunday in the Army, I find I have taken a severe cold and sore throat. This is aggravated by the constant daily windstorm and resulting dust and probably also by the sharply cooler temperature. Our food is not improving in appearance, or tastiness - it is often bad. I am thankful that a post exchange has been opened about two blocks away and we can buy a few items of bakery goods and candy bars to supplement the Army fare. It is also fortunate that all are compelled to bathe at least twice weekly. I think there are a few who manage to disregard this regulation, however, the closely cropped hair and daily shave cannot be hidden. The seven hours of drill, every day, gets monotonous as we pretty much do the same thing over and over again. I like the callistenics that are very much a part of our training. These exercises, if done conscientiously, are a great help in acquiring physical fitness. No gambling is supposed to be allowed in quar ters, but this rule is ignored and continues to be ignored. At this time there is no other pastime. The service organizations (Y.M.C.A., Knights of Columbus, Salvation Army) have not yet become active. The picture shows, pool halls, and stores, that appear eventually, are not yet in operation. On October 2nd, those whose smallpox inoculation, did not "take", get another one. In early October, a Y.M.C.A. has opened within walking distance. The typical Kansas wind starts up every morning. It blows clouds of dust through the dry air. Visibility is often less than a block. My cold and sore throat are not improving under these conditions. On October 5th, General Wood gives an inspiring talk to the troops assembled on a hillside. He must be an optimist if he expects much from us. We do not yet appear very soldierly as we do not have complete uniforms. The uniforms do not fit well and are generally of a poor quality material. The food is not improving much, if any at all. A typical meal is a tablespoonful of what is supposed to be potato salad, a big gob of fat pork cubes, Navy beans, and water to drink. For breakfast a spoonful of hash, very strong of onions, a little gravy, bread, a small handful of corn flakes and 1/2 cantaloupe, picked too green. Page 4

Transcript

The second vaccination takes effect on many, including myself, causing illness, pain, and fever. We are relieved from duty and are glad to stretch out on our bunks. I am glad to find that now my cold is much better, although my throat is still sore. On October 11th, the Mess Sergeant tells me that, although he has kept all windows and doors closed, so much dust and fine sand has blown into the mess hall between the hours of 1 P.M. to 4 P.M., that the table tops look like concrete. That night, all of the group that came on [September] 21, are awakened at 11:35 P.M., told to dress and march to Regimental H.Q. to be paid the $11 for the eleven days we served in September Thirty-six more men arrive from Nodaway County, Missouri, These, in addition to the 85 men who arrived on October 3rd, increases our company strength to over 200 men. In addition to the 89th Division, there is also the 92nd, an all black Division. The traffic, necessary to maintain the approximately 90,000 men, and the dry weather here, are causing the worst dust storms yet experienced and lead to more eye trouble and sore throats, as well as badly chapped lips and faces. It becomes sheer torture for many of us to shave. A good happening, about this time, was that the Mess Sergeant offered to get a plate and cup of white enamelware, for every man if each of us would contribute 50 [cents]. This offer was eagerly accepted. A drive was being made, at this time, to get every man to buy a $50 Liberty Bond. As a special inducement, every purchase of a Bond may give us a week-end leave to visit our homes, or wherever we prefer. A week-end leave to visit their homes is out of the question for many who live at a great distance. I decided to take advantage of it and get home on the morning of [Saturday], October 27. I enjoy my brief visit, but, by the time I get back to camp, I have about decided the discomforts of the return trip were too high a price to pay for the short leave. The frantic war effort is causing a traffic problem on the railroads. According to the regular schedules of the rail lines, I should have arrived back in the camp before 10 P.M. on Sunday. Instead, I did not arrive until about 7:30 A.M. Monday and had to stand, or sit on the floor, because of the crowded cars. On Saturday, [November] 4, I get a pass to go to Manhattan to get my blouse altered for a better fit. I was fortunate to be issued this part of my uniform on October 17. I get this done promptly, then attended a church supper where I have chicken pie, creamed potatoes, Page 5

Transcript

baked beans, cranberry sauce and apple pie; all I could eat for 50 [cents]. I see a movie and get back to camp by 10 P.M. We are being worked pretty hard. Our training has now progressed about as far as it can without weapons. The company mechanics are put to work sawing out the pattern of a rifle from one inch boards. With these we can, in a way, simulate the manual of arms. Some time, about mid-October, we received a number of the obsolete Krag-Jorgensen rifles, the weapon that was used to put down the [Philippine] Insurrection, and by some of our troops in the War with Spain. There were sufficient of them to equip the sentries. After all, the sentries would have looked rather ridiculous walking post with a piece of wood. When I first went into the Army, I gave little thought to any sort of promotion. However, after two hitches on "Kitchen Police" (Army for those who wash the greasy cooking utensils, scrub the messy table tops, and mop the floor), and becoming aware that Corporals and Sergeants, do not perform these menial tasks. I begin to think more highly of the suggestions of the First Sergeant that I attend N.C.O. school. When the Lieutenant, who commands the platoon I belong in, compliments me on my proficiency at drill and makes the same suggestion, I acquire a copy of the Infantry Drill Regulations and study them. I also attend N.C.O. school. The principal instructor at this school is a young Second Lieutenant from another company in our regiment. He is thoroughly versed in his subject, has the right personality, and gives us a great many pointers on the duties and conduct of an N.C.O. Of all the officers I knew while in the service, he was the most outstanding. I was later gratified when I learned that he was among the first to be promoted to First Lieutenant, then to Captain, after we got into action. He was wounded in WWI, in WWII, and in Korea. Won many decorations, and was retired, after more than thirty years service, as Brigadier General Arthur W. Champeney. The reader may be interested to know that this officer served under General Clark to command a problem regiment in Korea. He was wounded in WWI, in WWII, and in Korea. The wound in Korea was by a sniper's bullet which missed his heart by only an inch. Along with a number of others, I was made a First Class Private about October 15. On [November] 3, we get forty new m17 rifles. As Acting Corporal, I get one. These rifles are covered inside and out Page 6

Transcript

with a thick coat of sticky grease. It is about a three and one-half hour job to remove all this grease. It takes a supply of rags in order to pick up the grease on the surface. To get it out of the screw slots, and corners, a sharpened stick is suggested. I get a cheap tooth brush which is much more efficient. Doing the manual of arms, with the new weapon, is quite different from going through the same motions with the wooden pattern. The m17 weighs about nine pounds, the wooden pattern a tenth as much. Every day a Squad is designated to do housekeeping chores in the barracks, and outside. This includes, of course, the mess hall and kitchen. On [November] 7 it is my squad's turn to get this duty. As the Acting Corporal, I find that I become a messenger for the First Sergeant, the company clerk, and the company commander, as well as having to supervise the work being done by the other members of my squad, except those in the mess hall and kitchen who are under the Mess Sergeant's control. I am kept busy, but find this an interesting experience. I get to know the Regimental Surgeon, Capt. Bloch, a friendly man with whom I am destined to have more contact in the future. I am still fighting the cold and sore throat that has been troubling me for more than a month. The constant dust storms, lack of heat in the barracks, and no hot water, all may be contributing to this condition. We are all glad when our food gets better. On Sunday, [November] 11, the menu for the noon meal is chicken (from September cold storage] and gravy, mashed potatoes, butter beans and corn, fruit salad and ice cream. What I wrote earlier about the cooks was not complimentary. If now I retracted what I then wrote, I do not think I would be entirely truthful. As time went on, there were changes in the personnel, under the Mess Sergeant. Among a group of raw recruits that make up an infantry company, there are a few who cannot "pick up the cadence". That is - keep step. In all armies, it has ever been deemed essential that all men in a unit respond to commands to drill, march, or maneuver as one, and in perfect cadence. Those few who seemed unable to do so were either transferred, or were made cooks. It is to their credit that they often did well. Early in November, a requisition came for the transfer of twenty-five men to go to another Division. The effort to fill the National Guard and Regular Army Divisions with volunteers was not successful. We eventually learned that men who had been transferred out of our unit were sent into the 35th Division and the 3rd Division. This periodic transfer of men continued until only about forty remained in Page 7

Transcript

the Company. When a requisition for transfer of men came, the officers and the First Sergeant went over the roster and selected the men they thought they could best do without. Just before the first men were transferred out of our Company, a picture of the whole unit was taken. I buy one but am disappointed with it - too many people on too small a picture. Some of us get boxes from home containing cake, apples, cookies, etc. These are shared among us and are a real treat. The routine drill, callistenics, and hiking, continue with an occasional hour or two digging trenches and a parade about every two weeks. This Kansas dirt is really hard after the first few inches of topsoil is removed. It becomes a matter of loosening it up with the pick, and then shoveling it out. We are offered the opportunity to buy a $10,000 life insurance policy, and many of us do so - the premium comes out of our monthly pay check. This is no great hardship as there is little available for us to buy so, those of us who do not gamble away our pay, are readily persuaded to buy a Bond. On [November] 14 my sore throat takes a turn for the worse. My vocal cords are severely affected so I can hardly talk above a whisper. The surgeon excuses me from all duty. This condition continues and eventually I cannot talk. The Medical Officer comes by the barracks and gives me some terrible tasting gargle and tells me not to try to talk. While confined to quarters, I am asked to help the Mess Sergeant with his accounts and learn that the beef we eat costs the Commissary Department 16 [cents] per pound. I also help the Company Clerk some. Thus I get an idea of army paper work. About mid-November, our First Sergeant, and our Junior Second Lieutenant (a young man just out of law school), have words, with the result that our First Sergeant is transferred out. The Lieutenant is not popular with either the men or officers. I think him a good man who has not matured and is a bit on the impractical side. It is to be expected that some of the men who hope, or very much desire, a promotion, become obnoxiously obsequious to the officers. It is contrary to my nature to fawn on anyone, male or female, anyone in high public office, or any military officer or N.C.O. I may never get above Private First Class, but so be it. [November] 23 I draw a blank on Christmas passes. However, unknown to me, my father, getting the idea from the farm papers, applies for leave for me to come home on a two week leave to help with the corn harvest. It should be remembered that, at that time, mechanical cornpickers had not Page 8

Transcript

yet been heard of - it was strictly ear by ear of corn, hand work, and the many men drafted from farms was sorely felt at corn picking time. So it happened that I had the pleasure of eating Thanksgiving dinner at home. Unfortunately, several days after arriving at home, we had snow almost knee deep, and I did not get to help much in the corn harvest. I arrived back in Camp Funston on [December] 9. My throat is better and my voice is more normal. The streets have been oiled and, hopefully now, the dust storms will not be so severe and the sore throats will get well. All the men in the regiment get a heart and lung examination on [December] 17. It happens that I go on sentry duty at 4 P.M. on the 16th. Of course I do not get off duty until 4 P.M. on the 17th. When we get back to the barracks, we are at once ordered to go the the Regimental Infirmary to get our examination. I am somewhat taken aback when the Medical Officer, after examining me says, "you'll not do", takes my name and tells me to report to him at a certain hour the next day. I do as ordered and, after much listening with this stethoscope, he says "you'll do today, but I want you to report to a heart specialist tomorrow at 9 A.M.". Again I report as ordered and find eight others who have also been ordered to report to the specialist. The specialist appear s at 10 A.M. He announces that he has only thirty minutes to examine us and tells us to trip to our waist. Of the nine, he rejects only one. He hardly touches some of us with his stethoscope. I had evidentally shown definite symptoms three days earlier when I had just completed 24 hours of sentry duty. I recalled that on occasions, when I had to exert myself strenuously for an extended period, I seemed to become unduly exhausted. I was to become more aware of this as time went on. One very good thing came of this heart and lung examination. Two men from our company were found to have active cases of tuberculosis. They were immediately discharged from the service. These men may have transmitted this dreaded disease to others. This was quite possible under the crowded conditions of the barracks at that time. The blame for endangering the health of others falls on the examining doctors at the local draft boards. In our county, the examining physicians were elderly men with years of experience and should have detected the tuberculosis in the man who was from the same county I was from. Their failure not only endangered the health of others, but the men who were discharged were eligible to draw compensation and, doubtless, did so, costing the government many thousands of dollars. They had an "air tight" case for, when they were certified as fit for military, but the Page 9

Transcript

local Board, they were legally entitled to care and compensation for being disabled in the Service, regardless. There were thousands of such cases. Many were not given the more thorough physical check-up we were given on [December] 17, 1917, and were sent overseas where these physical defects were discovered. The matter was brought to the attention of General Pershing, who made strong protest to the authorities in Washington. It was about the first week in December when, after strong representations from General Wood, they put oil on all the streets in Camp. I hope this will help those of us who have sore throats and inflamed eyes. Just shortly before this, they have gotten heat in our barracks, and we also have hot water for bathing, shaving and laundry. There is now also a commercial laundry we can send our clothes to. These conveniences have greatly improved the morale of the men. A quarantine, that was put in effect earlier when one man developed a case of the measles, should soon be lifted. There have also been a number of cases of spinal meningitis, which are causing much concern for the Medical Corps. They take cultures from the respiratory tract of all in an effort to locate carriers or incipient cases of the dreaded disease. Christmas packages for many begin to come in about [December] 22. Many of them contain food, which is shared with other comrades. An aunt, in St. Louis, sends me a package of candied dates that were so good I could only bring myself to share them with ten others. Everyone was given a package, by the Red Cross. My package contained three pairs of excellent hand knit all wool socks, donated by a ten-year old boy in Montana. I convey my thanks and appreciation in a letter and save the socks for the next winter (1918-1919). This proves to be a wise decision. The process of making soldiers out of green recruits in three months, or even twice that length of time, requires a great deal of hard work on the part of the officers of the various units and careful planning and supervision by the general officers and regimental Commanders. It should be remembered that the U.S. Army, before War was declared in April of 1917, consisted of about 200,000 men and officers. These troop were stationed in various small garrisons in the continental United States, The Hawaiian Islands, the Canal Zone, the Phillipine Islands, and Guam. The Officers were almost all graduates of West Point. There were National Guard units in the various states, but few, if any, of these, were any where near full of strength or in a state of combat readiness. The officers of these Guard units (companies) were Page 10

Transcript

customarily elected by the men of their respective units. This did not always result in a choice of competent officers and proper discipline. Under these circumstances, increasing the Army to more than 4,000,000 was indeed a Herculean task. That it was accomplished in one year, 6 months and 26 days, is almost incredible. The 3,800,000 man increase in the Army was no great problem. It was accomplished through the implementation of the Selective Service legislation enacted by Congress immediately following the Declaration of War on April 15, 1917. The problems were finding the Officers to train and lead these men; to clothe them; to house them; to feed them; and to equip them with weapons. The Officer problem was solved by setting up Officer Training Camps at designated Army Posts. Officer Candidates were put through a rigorous ninety day study and training course. The candidates consisted of volunteers, some of whom had varying degrees of military training, to those who had not had any. Some were regular Army Non-commissioned Officers who won Commissions from Second Lieutenants to Major. There were veterans of the War with Spain (1898), who were in their late forties, some of whom won commissions as Second Lieutenants and some, of course, won higher rank. I was told by one of the officers in my regiment that for some reason, a number of law enforcement officers won commissions. Of those who won commissions, in the Officer Training Camps, I was most impressed by the young college graduates and especially by the graduates of the land grant universities, such as our own University of Missouri. The number of lawyers, who won commissions was surprising. Some of the lawyers were outstanding; one of these was Captain Inghram D. Hook, of Kansas City. The two regular Army N.C.Os. that I knew, who were commissioned, seemed overly careful not to win a Purple Heart. The matter of clothing us was accomplished after a fashion. Much of the material in our uniforms was of an inferior quality. It goes without saying that, without a doubt, there was much profiteering by the suppliers. The housing problem was also solved after a fashion. The barracks we occupied at Camp Funston were not yet completed when we arrived in September, as I have noted earlier, heat in the barracks was not installed until late in November, and hot water became available about the same time. The problem of arming the men was finally accomplished with considerable effort, to put it mildly. Our regular Army's regulation infantry weapon was the Springfield caliber .30-06 rifle firing a rimless cartridge with a 150 grain pointed metal-cased bullet. Page 11

Transcript

It was a Mauser type, clip loading, repeating bolt action, rifle and an excellent weapon. It had been made in government Arsenals. However, these Arsenals were not equipped to manufacture these weapons in sufficient numbers to arm the 6000,000 combat troops that were planned to be put into action. Many years later I read that several of the first Divisions that were sent overseas, were armed with the Springfield. This may be true, The ultimate solution was that the War Department contracted with Winchester, Remington, and other arms manufacturers who had been supplying the British with infantry weapons, and were equipped to mass produce the British service arm. A slightly modified copy of the British weapon in caliber .30-06, technically known as the U.S. Rifle Model 1917, was adapted. It had a very strong and safe action, although, compared to the Springfield it was less streamlined and a bit heavier. By the time we entered the war, it had been amply demonstrated that the machine gun was a very necessary weapon. Miram S. Maxim, a United States citizen, invented an excellent machine gun in the 1880s. He demonstrated it to our Army Ordnance people, but the War Department decided we had no need for such a weapon. The inventor next demonstrated his weapon to the British and made a sale. However, the British did not manufacture many of the guns until after it had demonstrated its effectiveness to their troops in France. Maxim demonstrated his gun to the German General Staff and made a quick sale. When the war began, it quickly demonstrated its deadly effectiveness to the German high command, and many thousands of them were made for the German army. The Maxim machine gun was rather heavy as it consisted of three major parts: the barrel and firing mechanism; the tripod, and a water tank. Each of these parts made a load for one man. The remaining five men, of the gun crew, carried ammunitition when the gun went into action. When moving from one part of the front, to another, our machine gunners transported their guns and ammunition in cars drawn by a mule. A few machine gun Battalions used a small crawler tractor (Cletrac) to pull a number of carts. The Germans developed a lighter gun using the same barrel and mechanism, but eliminating the tripod. They used a small light pod, instead. This was attached near the muzzle and could be folded beside the barrel when carried. They cooled the barrel by air, eliminating the water jacket, thus making it really portable by one man. This was the gun that accounted for so many of our casulaties. We are later issued a light French automatic rifle - the Chanchat, a crude appearing air cooled gun firing the rimmed 8mm Label cartridge. Its accuracy was poor. Its only Page 12

Transcript

redeeming feature was its lightness. Two of these were issued to a platoon. After the Armistice we turned these in and were issued the new Browning automatic rifle - a superb weapon. The Germans had excellent trench mortars. One fired a 77mm shell and the other a larger one. They were mounted on a base plate, could be leveled and aimed accurately, and carried by two men. We had what was known as the Stokes Mortar, which was aimed purely by guess and found the range by trial and error. What little field artillery the army had was obsolete The artillerymen trained with the old obsolete three inch gun, and the 4.7 inch Howitzer, also obsolete, and wooden mock-ups, while at Camp Funston. Upon arriving in France, they were equipped with the French 75mm field gun and the 155mm Howitzer. They had to be trained with these and did not get into action until some time after the rest of the Division. Although I get a blouse in early October, which completed my uniform, it was several weeks later before all were completely outfitted. In the group of draftees that joined us in October, was a man from St. Louis, who was quite portly. We did not have a pair of breeches to fit him. The best we could do for him wa one of the largest we had and it lacked about four inches, of the top buttonhole, reaching the top button. However, after about five weeks of drilling, hiking, callistenics, and army fare, his breeches were a good fit. About the time we were all fitted with a complete uniform, we were issued blue denim jackets and band top (no bib) overalls of a rather poor quality. These were worn at all times, except when on sentry (guard) duty, parade, or leave. This made it easier to keep the O.D. uniforms in better shape. Soon after the Company was fully armed with the new M.1917 rifle, we fired a full course on the range. The entire Battalion camped in their pup tents. Fortunately the weather was agreeable and, I think, many of the men enjoyed it. I know that I did. Living in the tents was good training and, getting better acquainted with the rifle, as an absolute necessity. Some of the men had never fired a gun of any kind. We fired a 100, 200, 300, and 600 yards. At the shorter ranges we fired both at will and timed rapid fire. At 600 yards, firing was at will - we could take as much time as we wished. Rapid fire consisted of firing ten aimed shots in ten seconds. We were instructed to press the rifle butstock firmly into our shoulder to get better accuracy and also to minimize the effect of the recoil. Many failed to do this, especially in the hurry of getting off ten shots in ten seconds. The result was many Page 13

Transcript

bruised shoulders as the recoil of the 30.06 was rather heavy. I was perhaps more fortunate than many of the men as I was not only familiar with a small caliber rifle, but also with a 12-gauge shot gun which had almost the same recoil as the service rifle. I enjoyed firing on the rifle range. After I completed firing the full course, I am assigned to duty in the pits marking targets and recording the scores. This was also good experience for those of us who were later to help train new recruits. It also taught us what the sound of a high velocity bullet is like - a sharp crack, much like the report of a .22 caliber rifle firing a .22 short cartridge. While we are at the rifle range, the company field kitchen is with us, and we get our regular three hot meals every day. One day the Regimental band comes out to serenade us. When all have fired, the First Lieutenant, who now cammands the company, orders me to return to barracks and tell the Captain "that the men are getting ragged and dirty and I think the company should be ordered to return to barracks". He specifically orders me to use his exact words. I am glad to do this as I go and come back by bus and have time to get a bath before I return with the requested order. The reader may wonder why the First Lieutenant did not communicate by telephone. The reason is, there was no telephone in the barracks, and none near the rifle range. Several days later when the scores of all who fired the course are compared, I am informed that I have tied, with two others, for high score. I knew that I had scored 89 points, out of a possible 100, at 600 yards, but had not added my scores at the shorter ranges. On [December] 25, a comrade and I get a pass to go to Manhattan. We plan to go in time to attend a Christmas service at the church of our choice, but the train, asusual now, is late and we miss this. We have the noon meal at the Gillette Motel - turkey and all the trimmings. The day being very pleasant, we walked around in the campus of the Kansas Agricultural College, at the suggestion of my companion, a school teacher in civilian life. We take in a picture show and are back at our barracks at 10 P.M. The weather remains pleasant and, on [December] 27, I join a group that has not yet qualified at the range. Having qualified, I do not fire but mark scores. We march the 7 1/2 miles. The weather begins to turn much colder in the afternoon and we march back. The fifteen miles march, and activities on the range, make a long tiring day. We sign the payroll on Saturday and are ordered to turn in one pair of breeches and a shirt (we had two pair of O.D. breeches for a month or Page 14

Transcript

or so, also three shirts. Don't know why, unless some other units are needing them. We get a very thorough inspection (the usual Saturday routine), but unusually thorough this time. It has gotten very cold. I am glad it is Saturday so we do not have to go out to drill or hike. At midnight, on [December] 31 - [January] 1, 1918, the fire whistle sounds and all fall out as we always do. The Captain, and one or two other officers, come in as we are all about ready to evacuate the barracks, and tell us it is just to wake us up to see the new year in. Whistles blow, bands play, and we are informed there will be no Reveille in the morning, and we can sleep as long as we like. However, from force of habit, we get up as early as usual. The second Officers Training Camp has just turned out a newly commissioned group of officers. A number of them are attached to our company to get experience commanding troops. Some of them cannot remember which command to give next. It gets boring and very cold, so, as the officers get even colder than we, they settle for a hike and we get back to the barracks at 1:40 the morning of [January] 2. The new officers stay with us through [January] 5. We hike out to the parade ground, which is a relatively flat area about two miles north from camp. The whole Third Battalion goes. Captain F., and the Adjutant, ride a couple of shaggy-haired, sorry looking horses, at the head of the column. They both appear to be very amateurish horsemen. The new officers command the troops through the parade and cause a lot of foul ups, much to the disgust of the troops. Very cold weather is with us so we do hikes in the morning, and get lectures in the afternoons. On [January] 9, we go on a night problem and get very cold. Although we signed the payroll [December] 29, we have not yet been paid on [January] 12. Page 15

Transcript

Camp Funston, [January] 12, 1918 I am perturbed because we have not yet been paid for December. I am down to $2.00 and want my picture taken. I have lent a comrade, from the town nearest our farm home, $8.00. He has won the opportunity to go to O.T.C. and needs money for a new uniform. The whole camp is now in a dither. On Friday evening, [January] 11, at 8:30, the bank was held up. Three employees, who were in the bank, were killed by a man in a Captain's uniform. He covered the men with a gun, had one man tie the hands and feet of two, then he tied the third man and then brained the three with a hatchet, or similar instrument. After which he then took all the money he could find. In some way the robbery and murders were discovered rather promptly and the whole camp had been searched - except the officers. When it was announced that he robber was in a Captain's uniform, the guilty man committed suicide. The money taken was all recovered. One of the amusing things connected with this very shocking occurence was that when our Junior Second Lieutenant heard that the robber wore a Captain's uniform, he was highly incredulous and flatly stated "that no officer could have done such a thing!" It turns very cold in mid January, so we take occasional hikes, but mostly we have lectures, or other indoor instruction - temperature down to -30 [degrees]. Fortunately we now have ample warm clothing. Colonel Nuttman lectures to the N.C.Os. - tells us they are the backbone of the Army. More men are being transferred out to fill other Divisions. Soon only the N.C.Os. will be left. An article in the Kansas City Star, about the 89th Division, in describing the Division's training and personnel, says the N.C.Os. are "well trained and are the pick of the men who originally filled the Division to full strength". I do not fully agree with this statement, but would not comment on it at this time. I had been a private First Class, and acting Corporal, for several months. Because of my sore throat, and loss of my voice, I was in no condition to take the usual test for further promotion. The cold weather continues and I have another flare-up of sore throat. I have been wanting to go to Junction City, or Manhattan, to have a photograph taken and take advantage of the first Saturday Page 1

Transcript

afternoon to get it done in Junction City. We have more snow and the cold weather continues. Outdoor training is out of the question, mainly because of our only footwear is the hobnailed field shoe. I do not think we could wear enough socks in them, unless we got shoes two sizes larger than we now have. I am sure neither the shoes, or the socks, are available in quantities to supply all. One feature of our life here has improved very much. South of the barracks, besides the bank that was robbed, there now are picture shows, pool halls, and a few restaurants. The pool halls are a very good place to enjoy a few hours of occasional leisure. They are operated under strict rules - no profanity, no smoking, and no boisterous behavior, is permitted, and the cost of playing is nominal. When I feel well, and have the leisure time, I enjoy it very much. The articles of clothing I had to turn in have now been replacedby others, and of better quality. Besides the places of amusement mentioned above, there is also a large auditorium. One afternoon the entire Regiment (only officers, N.C.Os., cooks, buglers, etc. are left), are assembled in the auditorium to practice songs, along with the regimental band. I go along but cannot join in the singing on account of my sore throat and loss of voice. The approximately 800 voices, and band, are very impressive. A vocal solo, by a Captain Carlson, a native Kansan, is very good. I get my photographs in good time, but can find no envelope to mail them, so I package them securely and send them to my home folks for them to distribute to various friends, relatives, and the very special girl friend. The cold continues and my throat and voice do not improve - cannot talk above a whisper without intense pain. By February 5 the weather has moderated, for a welcome change. I am getting the Mumps. My former acquaintance, Capt. Bloch, sends me to the Base Hospital, at Fort Riley. I am sent to the wrong section of the hospital, but the next day, [February] 6, I am transferred to one of the old three-story Cavalry barracks. I am told there are about 300 Mump cases here. Bathing and toilet facilities are in the basement. The kitchen, and mess hall are on the third floor. I am assigned to a cot on the first floor. There is no room service, except if you need medication, the orderly will bring it, usually, after a considerable delay. A Medical Officer makes the rounds once daily, as a rule. I was told there was a nurse on duty, but I never saw one. This is a poor excuse for a hospital and, obviously, no place for men suffering from the mumps. I can remember climbing the two long flights of stairs, to the mess hall, only once. I remained on my cot as much of the time as possible and wished Page 2

Transcript

that I had the mumps when I was eight years old. An Orderly took temperatures twice a day. After being in this so-called hospital, for a week, and beginning to feel very sick, the Medical Officer tells me he is going to send me to the Convalescent Barracks, at Camp. I protest that I am just beginning to feel sick. He tells me, "you've been here long enough". The seats, in the ambulance, were lightly padded. The gravel road was full of chug holes. When I arrived at the Convalescent Barracks, I was very grateful when the Medical Sergeant in charge showed me a cot close by. The Sergeant took my temperature and gave me a hard look. He notes that I do not go to supper, and brings me a cup of broth. The next morning he took my temperature and announced "you're going right back to the Base Hospital". I did, and this time on a stretcher. The Ward I entered, at the Base, was in a newly built, temporary building. There were about twenty, or more, beds, all occupied. A Medical Officer was on call around the clock. A nurse, and Orderly, were on duty 24 hours a day. I was given the best of care. I was very ill. About all I remember of the first three days, is that I was frequently aroused, from what seemed a drugged sleep, to find the nurse applying glycerine to my severely chapped lips, or sponging my face with a wet towel. When I am finally discharged from the hospital, after a long siege with the mumps, I am back in the Convalescent Barracks. A letter, written to my folks on [February] 25, tells them that I went to the Hospital, with the mumps, just three weeks ago, that I am still not entirely well, and have a severe head cold. An article in the Kansas City paper tells of a "clean up" in the Medical Corps. Many doctors have been dismissed from the Service and others have resigned. I hope those responsible for the conditions I found, in the old Cavalry Barracks, have been dealt with so no more harm will come to those who are ill and helpless. Actually, the Doctors in the main, probably did the best they could. The blame lies with the higher authority, in Washington, who continued to draft men throughout the winter when there was no suitable housing for them. Thousands of men were put into tents, in the bitter weather, without heat and adequate attention. Many died, in those tents, from the senseless exposure. We have, for months, been hearing about the new recruits dyin in their tents on the reservation. On [February] 28 I am back in my own company barraks, suffering from a severe earache, as well as an increasing soreness back of my ear. I realize I may be in for trouble when I report sick at the Regimental Page 3

Transcript

Infirmary and they find I have a fever. An ambulance picks me up shortly and I soon find myself back in the Base Hospital on March 2. They give me an aspirin, for the pain, and take two blood samples daily. On the third day, the surgeon tells me "it looks like I am going to have to carve on you". I have surgery the morning of March 6. The mumps, especially when there is a relapse, as in my case, causes severe build up of poisons in the body. In my case, the entire left mastoid was removed. I was so weak, from loss of blood, that I was unable to raise my head from my pillow. Healing was a very slow process I was always in considerable pain. I was finally discharged from the hospital, with a hole in my head, a constant noise in my left ear, and severely impaired hearing, on April 13. I spend a few days in the Convalescent Barracks and then back to Company I. I return to my Company April 14, my 23rd birthday anniversary. I am still weak and tire very quickly. An order from the Chief of Surgery at the Base Hospital, states that I am to be excused from duty and am to be given a twnty-one day furlough. While I was in the hospital, I was told by some of the staff, that there was a division of opinion, among the surgeons, as to the advisibility of allowing the mastoidectomy cases to be returned to duty, or to be given a medical discharge. In the light of my experience, I am inclined to think the latter course should have been followed. My hearing improved, to some extent. But, due to the very considerable difference in the acuteness of hearing between my left ear and my right ear, I find it difficult to locate where sounds come from. When there are two sources of sound, or more than one person talking, I can understand very little, if anything, either says - a severe handicap for a soldier - especially in combat, and a handicap the rest of my life, besides the annoyance or the continuous noise in the affected ear, the rest of my life. There are now about 45 men left in each of the Infantry companies in the Division-cooks and N.C.O. cadre. They have been fully equipped and look like real soldiers. These are the men the article, in the Kansas City Star, described as "the pick of the bunch". They will be the men who will do the most to train the 180 recruits we will soon get. I now learn, with pride, that my name was always on this list of "indispensibles", so I was in no danger of being transferred at any time. Page 4

Transcript

At the noon mess, the day I return, the menu consists of pork chops, with all the trimmings, and pumpkin pie for dessert. Shortly before I was discharged from the hospital, our First Lieutenant (Mabel) was admitted for eye trouble. He had requested that, when I had the opportunity, I bring his toilet kit and some clean clothes. I do this on the afternoon of the 14th. I have another reason for going there as I think I have some letters there for me. I am not disappointed when I get several from home, and three from the very special girl friend. When I first went to the hospital I was wearing the blue denim fatigues. They put away all my O.D. uniform, underwear, socks, shoes, hat, rifle, bayonet, pistol, belt, and complete pack. So, I look it all over to see that it is all O.K. as I will wear my O.Ds. home. I arrive, at home, on Friday, April 19, and enjoy the fresh air, good food, and rest. I enjoy every minute of it and regain my strength. It is rather difficult to part from the home folks, and the very special girl friend. The journey from Camp Funston home, and return, are comfortable as trains are on time and not crowded, as was the case the other times I made the journey. I arrived back at Company I barracks in time for breakfast on May 9. Spent the day drawing my equipment and readying it - cleaning and oiling my rifle and pistol. The Battalion is in tents at the Rifle Range and they have some new recruits. I will join them tomorrow. There is the usual Kansas wind. It is blowing up an awful sandstorm. Sand is coming thru the cracks in the walls of the barracks, covering floors and bunks like last Fall. I get on the electric car, in the morning, carrying pack, rifle, pistol, and all, to join the rest of the Company. I fire the full course - 250 rounds. When the the scores are tabulated, mine, at 600 yards, has not been equaled by anyone else in the Company. There are other troops here - the 353 Infantry and some from the 92nd Division (black). Our band came from Camp Funston and serenaded us, one evening. We break camp the morning of May 14 and march back to camp, carrying field packs. As we carry no ammunition, our load weighs about forty pounds. It is very warm and we are all tired after the 7 1/2 mile hike. We are to get another group of about 65 men, which will give us a company strength of about 175 men. We are due to get more recruits. They arrive about mid-month - from Camp Grant. After brief instruction, they are required to fire a course at the rifle range. I am ordered to take two of them to the range one morning. One of them speaks no English. I take them on the trolley to avoid the 7 1/2 mile hike. We are Page 5

Transcript

not enthused about the men from Camp Grant. They are from Chicago. Many have never been out of the big city. We also get a contingent from New Mexico. Many of them are Indians and speak Spanish. One cannot speak English at all. Our Company is a cross section of the United States, from Chicago to the Rio Grande. By May 18, we are in the midst of stenciling all pack carriers, haversacks and eventually our barracks bags, with the Regiment number, Company letter, and individuals number -mine is 356131. All the old men - the N.C.Os - are kept busy. It is evident we are shortly going overseas. All the Company property - the contents of the Supply Room - clothing, shoes, all ordnance and records, are boxed. The boxes are labeled with Division, Regiment, and Company numbers and letters. The same is true of the typewriter and filing cabinet in the Orderly Room. Also the Field (rolling) Kitchen. On May 22 we seem to be about all packed. We may not tell, or write, when we are to leave, or where we are going, but it is well known anyway. All the old men are kept very busy. There have been frequent inspections to see that every man is properly equipped. Every minute that could be spared from clothing the recruits, and packing, have been devoted to teaching them the basics of drill so they can be marched, and maneuvered, without confusing too many of them. We also get a partial change of officers. Capt. W. B. Finney is replaced by Captain Dale D. Ernsberger; Lieut. Frank E. Strain is promoted to First Lieutenant and replaces First Lieut. Mabe; Second Lieut. Wm. P. Ellison fills in for First Lieut. Strain. Second Lieut. Mattoon is replaced by Second Lieut. Julius C. Moreland; First Lieut. Jerome E. Moore becomes Bn. Adjutant. Eventually there will be other replacements of officers as time passes. As I recount the events, and activities, in this narrative, there are some that were humorous, as well as some that were an incident that occured in October. We had hiked to an area where we often went for drill and maneuvers. The Captain had ordered all the Corporals to take charge of their squads and put them thru squad drill. He was a short, and definitely a portly man, with a rather high-pitched voice. He tried hard to present a military appearance, but nature was against him. Like the rest of us, he had hiked all the way to this area from Camp Funston and was, doubt less, a bit leg weary. He sets a wooden box on end and sits down, ramrod straight, to watch his Corporals do their stuff. He turns from side to side in order to see all he could and, just as I was immediately Page 6

Transcript

to his front, the box collapses and the Captain takes a very undignified tumble It was an effort for me to keep a straight face, but gave my squad a "column left" and got away from the immediate vicinity. Others saw the Captain's tumble but, like myself, suppressed their laughter until later. As told earlier, the Captain was not permitted to go overseas with us. The rumor was that he had failed to pass the psychiatric test that all officers were required to take. First Lieut. Mabe, a veteran of the War with Spain, in many ways the most competent officer we had, failed to go overseas. He was well into his forties. His age may have been the reason for his transfer, but the fact that he was an immigrant, from Germany, may have been the deciding factor. 2nd Lieut. Mattoon also was left behind. He, like later General Champeney, attended a number of our Regimental reunions, in Kansas City. He was in the Service, in WWII, as a Judge Advocate Colonel. Company I, along with other companies of the Regiment, boarded a train for our Eastward journey, on the morning of Friday, May 24, 1918. Compared to the transportation we had on the rest of our journey, we traveled in luxury - in Pullman cars. I was so fortunate that I got to share a stateroom with two others. I took the upper bunk, by choice, and truly enjoyed the trip. The Spring weather was especially pleasant. I enjoyed the scenery. I had never traveled much before as I was born and raised on a farm and never had the time, or money for it. Our train halted briefly at the town of Moberly about dusk.We were ordered out of the cars and marched up and down the streets for perhaps a quarter hour. Evidentally our arrival had been announced earlier as there was a considerable crowd at the depot The relatives of a few of our men were there. The crowd applauded vigorously when we changed direction, or formation, at the various commands. Due to the fact that the vast majority of the men were poorly trained, ours was a ragged performance, but the farmers, and the townspeople knew no better. Anyway, it was good to get a bit of exercise. At daylight, on May 25, we were travelling across the Illinois prairie - rich black dirt. The corn was about six inches tall and of a sickly yellow color from too much moisture. This was also coal mining country as was indicated by the huge piles of slag that dotted the landscape. On May 25 we stop at a town in Indiana for exercise where mostly boys came to watch us. I heard them say that we were all from out West and Page 7

Transcript

were all cowboys ! Our next stop, the late afternoon of the 26th, was at Shenango, Pennsylvania. Even to the casual observer, it was evident that it was older then our towns and villages in the Midwest. We drew only a minimum of attention, except for two Khaki-Wacky young girls who chose to be kissed by all the men that came along. When we passed thru a large city, we saw the largest locomotive ever built, up to that time. We passed through the part of the state settled by the German immigrants brought over by William Penn, now better known as the Pennsylvania Dutch, also Amish. I marveled at the huge and solid barns on their farms. The farther East we came, the better the railroads and the more paved high-ways. Two boys, on a motorcycle, and people in a Pierce-Arrow touring car, easily kept up with our troop train along a stretch of paved highway that paralleled the tracks. In New Jersey our train slowed its speed as we passed through an attractive town called Tuxedo Park, that impressed me. We arrived at Hoboken, New Jersey, transferred to a ferry, and then boarded a Long Island train for Camp Mills, where we arrive late in the afternoon of May 27. The trip, across the Bay, was a novel experience for about everyone. The ferry that navigated forward, or backward, with equal facility, was about as interesting as the Statue of Liberty, the Woolworth Building, Battery Park, and the bridges from Manhattan to Long Island. We were quartered in squad tents - again had to make do with cold water for showers and shaving. We were subjected to a number of inspections, down to extra shoe strings. It was only a minor annoyance to the rank and file, but the Officers, apparently, became annoyed. It seemed that if only one man was found short of a pair of socks, or had lost a knife, fork, or spoon from his mess gear, the entire company had to undergo another inspection. In a conversation with the First Sergeant, he stated that the Captain was getting disgusted. I asked why did the Captain not put the responsibility on the N.C.Os. for such inspection. He told me the Captain did not think the N.C.Os. were competent. My reply was that if I were Captain, and had a Corporal, or other N.C.O., who was that incompetent, I would demote him to Private at once. He told the Captain what I had said and, the next day, orders were issued to the effect that Corporals were to inspect their squads. I had put my foot in my mouth! That was the last inspection we stood at Camp Mills. We had to wait until June 4 to board ship. We did little here as there was seemingly, no room to drill more than a squad any where. Our quarters Page 8

Transcript

adjoined an airfield. There were planes in the air all day, weather permitting. We had frequent showers, but the rainfall quickly disappeared into the coarse sand. I think about everyone got tired of the lack of activity. One of the recruits, in my squad, challenged me to play Blackjack (21). I had little interest in gambling, but the boredom of inaction impelled me to accept the challenge. We started out at a dime a game. I won, rather consistently, and he reacted by wanting to play for a quarter a game. My luck continued until he gave up in disgust, after I had won about five dollars. I wrote a number of letters as I knew it would be weeks before I could mail any more. I received some that were read, and reread often, before I would get any more. On the morning of June 14, we are ordered to roll our packs. Immediately after which we pick up all our gear and board a train that takes us to the vicinity of the Cunard Steamship Line docks, in New York City, where we board the Cunard Liner Coronia. This ship was, at that time, already some twenty years old. She had a coat of alternate black and white paint in a most irregular pattern. They called it camouflage. I question that it camouflaged the vessel with those two tall smokestacks showing up like lighthouses. We were shown to our quarters by the sailors, in a comparatively short time - there were about 6,000 of us. I say quarters. I think I should describe them. There were tables built like the picnic tables we are all familiar with. A table with benches attached to both sides. They accommodate 22 men. As we filed into the compartment, a sailor counted off 22 men to a table. Rolled hammocks were attached to numbered hooks in the ceiling. At night these hammocks were unrolled and the free end attached to another hook, stretching the hammock out long enough to accomodate a man. We were so crowded when all were in their hammocks, that an occupant's head could touch the man's foot, behind him and, his feet could touch the man in the hammock ahead. He could touch the men on either side by moving his elbows outward. The air, when all were in their hammocks, was unbelievably foul. Two days before we sailed, one or more, German submarines had sunk a number of small vessels within forty miles of new York Harbor. No one, except the necessary crew members, were allowed on deck as we steamed out to sea. A Blimp was flying over the convoy, as were also several planes. A number of destroyers were racing around the convoy, also on the lookout for submarines. Fortunately for us, our quarters were about, at least, eight feet above the water line so we could see a little of what was going on. Of course, our convoy left us when darkness Page 9

Transcript

set in, except for a British cruiser that stayed all the way. We were each equipped with a life jacket. They were made of canvas, filled with cork. The canvas had originally been yellow, but the color was now undiscernable. The salt air made everything one touched feel greasy, or was it the salt air? Nothing seemed to be too clean. We are fed twice daily. The morning meal consisted of coarse brown bread, orange marmalade, and tea. At about 4 P.M. we were offered either boiled beef, or boiled mutton, potatoes (unpeeled), and, of course, the inevitable tea. When the men, at my table, were counted off, the sailor saw the chevron on my sleeve and said that I was to see that all got their fair share. I tried to perform this duty the best I could, except at one meal - the rabbit stew. About noon, as I was coming down the ladder, I noticed the elevator had brought up some rabbits from the cold storage hold. They looked just like the old cotton-tails we used to kill, for the market, when I had time off from farm work and needed a little money. They were skinned and drawn (gutted). The head and feet were left on, and sometimes we did not get all the hair off the tail. Not infrequently an inch, or so, of the colon were left with a few pellets of manure in it. I stopped to watch the two sailors who were readying the rabbits for the stewpot. One sailor had a meat fork, about three feet long, with which he would spear a rabbit, then pitch it on to the butcher's block where another sailor, with a cleaver, chopped off the head and the legs, raked those into a tub, and then proceeded to chop up the rabbit into three or four pieces. I immediately developed a queasy feeling with regard to the afternoon meal. When the food was brought to my table I took the large spoon, that was in the container, and lowered it to the bottom, then slowly raised it and drained part of the contents back into the container. I found that the spoonful I brought up contained a quite liberal portion of rabbit hair, and rabbit dung. I replaced the spoon in the stew, shoved it to the nearest man, and told all to help themselves. I went back upon the deck. Fortunately we had a canteen on board where we could buy candy bars, and a few other items, to supplement the unappetizing, and sometimes revolting fare. I was now very thankful that the recruit had challenged me to the Blackjack games. I was down to about two dollars at the time. With the additional five I won, I had sufficient money to get the food items that helped make life barely bearable. Our convoy's course was far to the NOrth of the usual shipping lanes between New York and the British Isles. In fact, we were, for a few days, Page 10

Transcript

so far North that we had less then four hours of daylight. Submarines, of that day, were only a faint hint of the silent and unbelievably deadly atomic-powered underseas dreadnaughts that have been developed in the late 1970s. The Germans had comparatively few of them, but they had exacted a heavy toll, in ships sunk. Our convoy's course was so far North that submarines could not operate in the cold waters of those northern latitudes for the simple reason that there was no practical way to heat the crew's quarters so the men could function. We experienced a lot of rough water. When we left New York Harbor, the sea was relatively calm. In fact, the light wind caused only a ripple. We could open portholes and look out. However, this favorable condition did not obtain for long, and all porthjoles had to be kept closed. One evening we were encountering especially rough water on our starboard bow. Some of us were in our hammocks. I was among them when, suddenly, there was a deafening crash. It was followed, momentarily, by wild panic as many assumed we had been torpedoed. It so happened that, as I lay in my hammock, my attention had been called to a group that was in line with the cause of the commotion - one of the portholes had not been properly fastened so that, when a heavy sea crashed against it, the fastening gave way and a barrel, or more, of sea water, suddenly crashed down on a table top. There happened to be a few cool heads nearby who immediately saw what caused the crash and were able to stop the panic. This gave us a good idea what would occur in case we would be torpedoed. Really, in such an instance, there would be few, if any, survivors, as there were nowhere near enough lifeboas, and rafts, to accommodate passengers and crew, and no chance for survival in the cold water. In any case, the convoy would not stop to pick up the people from a torpedoed boat because of the danger of more torpedoes from the sub. As General Wood was relieved as Commander of the Division shortly before we sailed, Brigadier General Frank L. Winn was now in command. I recall that on several occasions we were ordered to the upper decks as practice for a possible abandon ship order, and also to afford us a little much needed exercise. There was no recreation available, so we were very glad when the ships entered into the Irish Sea, from the North, On June 16. After twelve long days at sea, during which we always wore the bulky life jackets (except for the several times we got a shower bath by dousing one another with buckets of sea water) the prospect of soon discarding them was pleasant to contemplate. As we came down the North Channel, the sight of the coasts of Northern Ireland, Scotland, and the lush green of the Isle of Man, were a welcome sight. However, Page 11

Transcript

sobering reminders that there was a war going on, were the masts of sunken ships we encountered. Those were shockingly numerous as we neared the port city of Liverpool, where we disembarked. Our ship was heavily loaded with an assortment of freight, as well as the 5,000 troops, and crew, The ship was slowly eased into the dockside, accompanied by the rendering of the British national anthem, and also our own, by our bands. Once along side, no time was lost in disembarking as all of us, after discarding the greasy life jackets, had gotten into our gear and picked up our rifles, ready to go. We formed into a column of Squads (four men abreast), and marched through the streets of Liverpool to what was called Knotty Ash Camp. The narrow streets were paved with brick, or stone, and our hobnail field shoes announced our approach to all and sundry. My place, in the formation, was behind our Platoon Sergeant. At his left was Capt. E. I was in the first rank of soldiers and, or course, was all eyes to see all I could of the first European city I was ever in. We had not gone far when the stall boys would run alongside the column with the usual request, "hey, Yank, have ya got any cents?" To this the usual reply was, "No, if I had, I wouldn't be in the Army". One feature that struck us rather forcefully, was all the small brick cottages built side by side at the edge of the street (no sidewalk). All these cottages were very neat, with lace curtains at every small window. We saw only the very young, and the old; no young or middle-aged men or women on the streets, and all had bad teeth. We had not proceeded more than perhaps a quarter mile when I saw a toothless, but spry, old lady rush up to Capt. E. and, throwing her arms around his neck, enthusiastically planted a kiss on his cheek, to the evident embarassment of the Captain. KNOTTY ASH CAMP The afternoon was warm and sunny so we had worked up a sweat, carrying our 90 pound load, by the time we arrived at our destination. We were a bit disconcerted when we noted the very tall, tight, and unclimable barbed wire enclosure surrounding the mess tent, kitchen, and rows of Squad tents. Upon being assigned to a tent, we lost no time getting rid of pack and weapon. The next thing we sought was a drink of water, then a little rest. About 4 P.M. mess call sounded. We had worked up an appetite since the usual shipboard morning meal of coarse bread, marmalade, and tea. Our evening ration of more of the dark, coarse bread, cheese, marmalade, and the inevitable tea, lacked, noticeably, of satisfying our hunger. We are getting the same ration as the British. These people all look lean and, several times in brief conversations with some Page 12

Transcript

elderly men, we are told what a fine looking lot of men we are. Then, "We are sorry for you, but you'll never get back. Ye cawn't lick them Germans". It was very evident the common people, of England, were "licked." As we passed through England, France, and later into Germany, this became even more evident, especially of France. After supper we noted, in a small area between the mess tent and the nearest troop tent on the outside of the formidable fence, were some young children, mostly at a distance, and several youngish appearing women, who did not hesitate to proposition us, naming a very modest price "if you can get out of there". Thus was revealed to us, the reason for the unclimable fence - to keep these women out, and us in. Nevertheless, one of our regular Army Sergeants, managed to get out. He was missed, and for his brief fling at liberty and lust, he was reduced to Private. TO SOUTHHAMPTON The next morning after the usual breakfast of coarse bread, marmalade and tea, we marched to the railroad station and boarded a train. It was a bright, sunny day for the most part and I enjoyed the scenery. The English countryside can be described as clean, and generally well cared for. Even the smallest water courses, on the steepest hillsides, had been lined with concrete or rock, to prevent erosion. The land that was subject to erosion, due to its topography, was in grass. The several grand estates I saw, with the manor, or castle, set back in a well manicured park, looked the perfect picture of rural elegance. The rolling stock, of the English railroads, is smaller than ours is in the United States, but their rate of speed is quite fast and all out of proportion to the high pitched little whistle of the locomotive. We passed close by a city Coventry, I think it was, but made no stop until we arrived at Southampton in late afternoon. Almost all the houses, in the villages, appeared small and all were of masonry- a contrast to ours, mostly of wood. The thing I noticed, and which struck me as unique, was the lack of fences. There were some areas enclosed by stone walls, but livestock was either herded by a man, and his trained dog, or it was tethered. CROSSING CHANNEL TO LeHAVRE FROM SOUTHAMPTON There was considerable delay before we boarded the small channel steamer Prince George. When we did get aboard, I, for one, was on deck to see all I could as we steamed slowly down the estuary. I was particularly fascinated by a castle on the Isle of Wight. Our progress was timed so we began to get into the choppy water of the Channel at dark. Page 13

Transcript

A comrade, and I, began to wander around looking for a comfortable place to rest. There appeared to be none on the deck from where we had done our sight seeing. As we walked along a narrow passage, between cabin and the rail, a cabin door opened slightly and a crew man spoke softly and asked us in. He knew we would be hungry and that we would doubtless we willing to pay for food, and a comfortable place to sleep. When he offered us all the bread, roast beef, and tea, we wanted, plus a comfortable bunk, for a dollar, we accepted with alacrity. The roast beef was excellent and the bunk was well padded. When I awoke it was broad daylight and we were entereing the harbor at LeHavre. Our hosts had cautioned us that they were not really supposed to have guests so, after getting into our gear, we picked up our rifles, opened a crack in the door to see if the passage was clear. When it was, we stepped out quickly and joined our comrades on the forward deck. We did not get to thank our hosts as they were gone - at duty, I suppose. As the Prince George was being moored, our new First Sergeant, on seeing me, asked, "Where have you been?" "I've been looking for you". I told him simply that I had found a good place to sleep. The ramp was being lowered and I was ordered ashore. Upon my taking position, the order was given for I company to "fall in", to my left. This was the easiest way to disembark the troops from the small steamer in an orderly manner. The other units followed in the same manner after our Company moved out. when all had assembled, the column marched up a rather steep hill. The street was paved. A substantial retaining wall bordered it on the Harbor side. On the other side was a row of what evidentally were residences, all with a good view of the harbor. We stop at a so-called Camp. Our quarters look more like an old warehouse. We sleep on a board floor - the boards, simply placed side by side on the ground, are furnished with the coarsest wool blankets I ever saw. Facilities here are very poor. We eat from our emergency rations for breakfast, June 18, and live on them for almost a week. We leave this place, with no regrets, on the 19th, when we board a train for our training area in Northeastern France. We arrive at the railroad station nearest the village of Liffol le Grande, in the early hours of June 23. This journey, from LeHavre to Liffol le Grande, was the most trying we had so far undertaken. We were sandwiched into the third class cars with our weapons, and equipment, so tightly that if one man wished to move a foot, or a leg or two, others had to do the same. The distance traveled was about 500 kilometers, or approximately 300 miles. Due to the poor conditions of the French railway systems, it Page 14

Transcript

took us from the morning of the 19th, to the early morning hours of June 23, to travel this distance. Fortunately the French railways system was double track, evidentally, about 100%, at that time. Had it not been so, the rail system would have caused total disaster early in the war. Our troop train stopped many times, in the country side, evidentally to either make repairs, or to get up a sufficient head of steam, or both. The first French villages we saw were a novelty, with their small stone houses clustered together, and the inevitable church, with its tall spire. LIFFOL LE GRANDE AND VILLOUXELL It was still dark when the train stopped for us to get off in the midst of fields of farmland. It can be understood that all the troops were glad to get out and walk around a bit. I think our Company Officers understood this. I had a high regard for our Colonel, but when I heard him say, to our Captain, "your men seem to be quite restless", I was disappointed in him. The officers rode in first class cars and were not cramped for room, as were we. It took quite a while to unload such of our equipment as the field kitchens. For some reason, the guide who was to show us to our various destinations, did not put in his appearance for hours. I Company, together with the rest of the Third Battalion, occupied four temporary wooden barracks in the tiny hamlet of Villouxwell. The rest of the Regiment was quartered in Liffol le Grand. We, of the Third Battalion, were very fortunate here, although I doubt that very many of us were really aware of our good fortune at the time. The hamlet consists of not more than five houses, all of which were small and one, of which, according to its occupant, was four hundred years old. I have no doubt that was true as the door sill was of a very durable type of stone. It was worn down so far, in the place where most hobnailed shoe soles had come in contact with it, that a full grown cat could easily enter, although the door be shut. The hamlet was located at the foot of a forested area where a very considerable spring of cool clear water gushed out of a rock formation, was caught in a good sized concrete tank where we could always fill our canteens with cool water. This water was so pure, it was not necessary to chlorinate it - an unusual circumstance indeed. It was a quiet place. There was no public "cafe" dispensing alcoholic beverages. Those who sought such, had to walk over two kilometers to the village so, if they became inebriated, they could walk at least some of it off, coming back. Villouxell was in a typical rural area - farmland, although not the best in France. We could look to the South and see the village of Page 15

Transcript