Lincoln Dante article on John L. Barkley - November 1, 1962

Transcript

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE 1 [November] 62-2/1d NOTE: This is the first of a monthly series of articles commemorating the 100th anniversary of the Army's presentation of the Medal of Honor. Each article in the series will be on a Medal of Honor winner living in the Kansas-Missouri area. Without these men there would be no celebration of a "century of valor." FARMER JOHN AND THE MEDAL OF HONOR by PFC Lincoln Dante Speculation in early 1917 was that the United States would soon enter the war raging in Europe. All over the country, Men flocked to the nearest recruiting center to become part of the military build-up. John Lewis Barkley, a young Missouri farm boy, wanted to get in on the action. At the reception center he listened as the doctors tried to decide if his stammering was too bad to accept him in the Army. One doctor wanted him rejected, another praised his physical condition. Finally the doctors decided that the United States needed fighting men, not orators. The doctors had no way of knowing that John Lewis Barkley would win the Medal or Honor 13 months later. Barkley was born [August] 28, 1895, on a small farm near Holden, [Missouri]. When he was four, a crochet hook lodged in his throat, causing an infection. The infection was cured, but the accident made John Barkley stammer so badly that only those who knew him well could understand him. -MORE-

Transcript

[page 2] As a boy, he learned to hunt and shoot and track down game quietly. After graduating from high school, he went to Warrensburg State Teachers College where he was an aggressive competitor in boxing, football and gymnastics. John left Warrensburg early in 1917 to join the Army and was a happy young man when the doctors classified him "fit for service." Private Barkley enjoyed basic training at Camp Funston, [Kansas]. He drilled proudly with the wooden rifle he had carved and shot accurately with the Army-issued Springfield. On April 6, the United States declared war. A few days later, Private Barkley stood on the deck of the "Great Northern" and watched Newport News, [Virginia], and America slip over the horizon. Where the "Great Northern" docked at Bordeaux, France, he was disappointed because he didn't see the enemy hiding behind every tree. John spent his first six weeks in France attending an intelligence school. He was taught to be a sniper and a spy -- a special soldier. He learned how to use and maintain enemy weapons and was given a breech block for German machine guns. (When retreating, the Germans often left their machine guns behind, removing only the breech block to prevent their being fired.) After completing intelligence school, John and his classmates re-joined the 4th Infantry Division and their old Company -MORE-

Transcript

[page 3] "K" buddies and began the march to the front lines. The 4th set up camp a few miles from the front, and Barkley, now a PFC, was sent on an observation mission immediately. From an observation post in a partially covered shell hole overlooking the Marne Valley, he watched through his binoculars as the French tried to keep the Germans from crossing the Marne River. A few missions later, at the same place, he noticed a German officer standing behind a bush, not too far away, watching the battle below. Barkley watched him for a while, almost hoping he would disappear. Then Barkley lifted he rifle to the firing position, looking through the telescopic sight. He didn't want to pull the trigger, but this was war; he fired. The German lurched forward on the bush. Barkley had killed his first German. When night came, Barkley went back to camp to report what he had seen. He tried to sleep, but sleep never came. He kept thinking of that dead German officer. As a member of the intelligence "suicide squad," Barkley often had to go on sniping and observation missions. He still stammered incessantly, but he didn't have to speak when he was alone near the enemy lines. He liked his job. One bleak and miserable night, Company K was undergoing a terrific artillery barrage. Word was passed along to the men --MORE--

Transcript

[page 4] to fall back for a regrouping. Unfortunately, some of the men never received the message and Barkley was sent to let these men know the rest of the company would soon attack and to remain in the fox holes. Cutting through a small wooded area, Barkley heard a phone ringing and a voice yelling for it to be answered. He reached the phone and answered it, just as a German artillery shell exploded on a tree near him. He blacked out, and after coming to, made his way back to his company. The first words he spoke came out clear and unstammered. The shock from the artillery shell had ended his stammering. By [October] 6, 1918, the American and French armies had pushed the enemy as far as Cunel, France. That night, Barkley was given a telegraph key and sent behind the enemy lines on Hill 253 to relay information on enemy movement. In the dark, he made his way into enemy territory and chose a tree-covered shell hole as his observation post. The enemy was still and Barkley slept. It was daylight when he awoke and as he peered out of the shell hole, he found that he was in the middle of a field. There was a lot of enemy movement at the field's edge and Barkley knew he had to move to a better place or be detected. He noticed an abandoned French tank in the field but was reluctant to crawl to it because he would surely be seen. -MORE-

Transcript

[page 5] Soon an artillery barrage started and smoke covered the field. He got out of the hole and raced towards the tank, stoping only to pick up an abandoned German machine gun. Taking advantage of the smoke, Barkley left the tank and went about the field picking up all the ammunition he could find, over 4,000 rounds. When the smoke in the field lifted, he went back to the tank to sit and wait. The machine guns breech block was missing, just as he had learned in intelligence school, so he inserted the one he had been issued. German soldiers came out of the wooded area at the edge of the field and advance towards him, apparently advancing on Hill 253. Barkley was the only thing between them and the hill. He wasn't sure the gun would work as he inserted one of the belts of ammunition, but he could wait no longer. The machine gun fired perfectly when he pulled the trigger and the Germans fell. They came at him from three sides, and he had to keep swinging the gun around partially exposing himself. The machine gun soon began to overheat and to fire intermittently. It had to be cooled. Barkley searched the tank and found a can of French motor oil. He poured it into the gun and on his hands which were blistering from the gun's heat. His pause in firing allowed the Germans to put a 77mm gun into place and they began firing at the tank. One of the --MORE

Transcript

[page 6] shells hit the tank's track, and the explosion knocked Barkley unconscious for a moment. When he came to, blood was running form his nose and mouth. Because of the blood and the smoke pouring from the burning oil on the fun, he gasped for breath as he began to fire almost blindly. The 4,000 rounds of ammunition were almost gone. He could hold off the enemy no longer. He saw then that the Germans were falling back into the woods. He crawled from the tank to be met by the 30th Infantry Division, charging down from Hill 253. After a few days rest, he was back at the front in the heat of action once more. On one mission he captured a German soldier and in spite of the fact that the Germans had lost so many men trying to kill him as he fought in the tank, Barkley personally protected the German from harm. A few weeks later, Barkley and the other men of the 4th Infantry were relieved. They were sent to Meisenheim, Germany, an American occupied area, for rest and recuperation. On March 17, 1919, Private First Class Barkley was taken to the airfield at Andernach, Germany. The airfield was crowded with columns of men. Barkley noticed that the 4th division was there ahead of him. The men on the field were called to attention, an an officer began to speak from the platform in front of the troops. Barkley recognized General John J. "Black Jack" Pershing. - MORE -

Transcript

[page 7] The general read an order and called Lieutenant George P. Hayes and PFC Barkley to the front of the lines of men. General Pershing presented the Medal of Honor to both men. When Barkley's medal was pinned on, the general pinned it a little too deep and Barkley flinched. The general's aide--Major Douglas MacArthur--straightened the medal. After Major MacArthur straightened the medal, he gave Barkley the citation for the Medal of Honor, which Barkley folded and put in his pocket. Then the mustached French Field Marshal Ferdinand Foch presented the Medaille Militaire to Barkley and, as is the French custom, kissed Barkley on both cheeks. Barkley answered with a sneeze. Later Major MacArthur asked the young hero why he had sneezed and in his honest manner, Barkley replied, "When he kissed me, he put his mustache in my ear." MacArthur had to fight to keep from laughing. At the same ceremony, Barkley received the French Croix de Guerre and the Italian War Cross. The ceremony ended with the 90,000 men on the airfield passing in review for the two Medal of Honor winners, Barkley and Hayes. A few weeks later, Barkley made a voyage that many American soldiers of World War I would never make -- he came home. Reminiscing about the day he came back to Holden, Barkley said, "There weren't many people there to meet the train, only *MORE-

Transcript

[page 8] a few farmers. Nobody knew I was coming home. When word of my arrival spread around the town, most of the people came out to see me. They were glad to see me but I know not as glad as I was to see them. I never thought I'd come home alive.” They day after he came home, the farm boy who had been decorated before 90,000 men was alone in a field behind the Barkley house. There was plowing to be done. Today 67-year-old "Farmer John", as he is known by his friends and neighbors, is the commissioner of the Shawnee-Mission, [Kansas], park district. He has been called upon many times to give speeches but feels it would have been best if he stayed out of public life. "People expect me to know everything; I don't. I'm just an average American who was decorated for doing my job. There were many other boys who deserved it more than I; some of these boys are still in Germany and France and will remain there forever." "A boy needs three things in his life above all others: religious training, education training and military training and of these, military training changes the individual from a grown boy to a man, an American man." This is John Barkley's firm belief. In his home in Shawnee-Mission, John Barkley cherishes two things above all: a painting by Howard Chandler Christy of a proud farm boy in a World War I uniform adorned with medals, and a -MORE-

Transcript

[page 9] glass case containing a well-wrinkled piece of paper, the Medal of Honor, Italian War Cross, Medaille Militaire, Croix de Guerre, World War 1 Victory Medal and the Medaille De La Bravoure. On the Medal of Honor in the middle of the case and on the wrinkled piece of paper is the inscription: "For single-handed capture of Hill 253, [October] 7, 1918, John Lewis Barkley, Cunel, France." John Lewis Barkley, an American Famer, an American fighting man, an American, will live forever in the soul of the country he helped protect "above and beyond the call of duty." --30--

Details

| Title | Lincoln Dante article on John L. Barkley - November 1, 1962 |

| Creator | Dante, Lincoln |

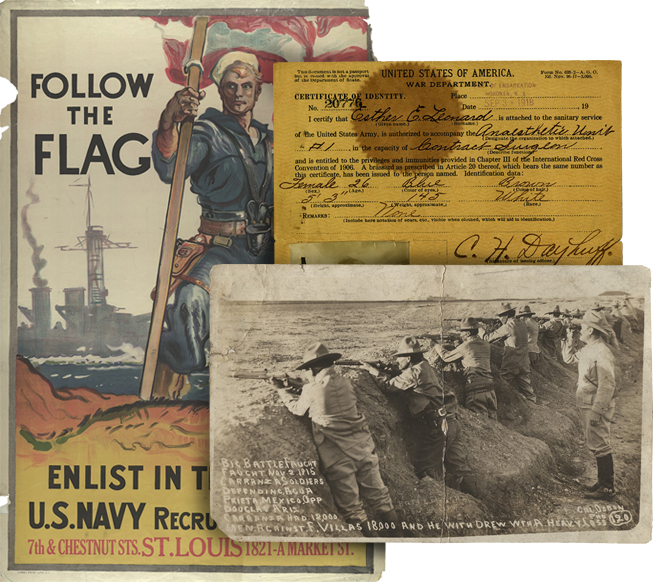

| Source | Dante, Lincoln. Article on John L. Barkley. 1 November 1962. John Lewis Barkley Collection, 1917-1966. 2010.102. The National World War I Museum, Kansas City, Missouri. |

| Description | In this article dated November 1, 1962, PFC Lincoln Dante wrote about the military experiences of John L. Barkley, including the situation that lead to his Medal of Honor. |

| Subject LCSH | United States. Army. Infantry Regiment, 4th; United States. Army. Division, 3rd; Medal of Honor |

| Subject Local | WWI; World War I |

| Site Accession Number | 2010.102 |

| Contributing Institution | National World War I Museum and Memorial |

| Copy Request | Transmission or reproduction of items on these pages beyond that allowed by fair use requires the written permission of the National World War I Museum and Memorial: (816) 888-8100. |

| Rights | The text and images contained in this collection are intended for research and educational use only. Duplication of any of these images for commercial use without express written consent is expressly prohibited. |

| Date Original | November 1, 1962 |

| Language | English |