US Women's Overseas Service in World War I

Photograph of Women's Troop Train Service parade - n.d.

Image courtesy of Missouri History Museum

With the entry of the United States into World War I in April 1917, women mobilized to show their service to the nation just as men did. At home women formed the front line of food and resource conservation, they volunteered for the Red Cross and other war relief organizations, and worked in war-related capacities. However, this essay focuses on another part of female war service, namely their overseas service. World War I marked the first major mobilization of American women in Europe in U.S. History. More than sixteen thousand women served as part of the AEF in sex-segregated environments in non-combat roles.1 Thousands of women worked stateside in the armed services (army, navy and marines) in order to free up men for war. Hundreds more traveled to France to work for other organizations related to the war, for newspapers, for relief societies, or as office staff for wartime agencies. If the First World War was a coming of age moment for the United States and its male citizens, it served a similar role for many American women. This essay briefly outlines four kinds of war service for women in World War I: military auxiliaries, hospitality staff, war relief, and medical work.

One of the most visible ways that women participated during the war was as auxiliaries in the American Expeditionary Forces (AEF). This was waged work, so it attracted women interested in serving but without the means to fund voluntary war service. Women wore uniforms that complemented soldier’s garb, but that retained a “feminine” look. Many of the women worked as drivers and cooks, but they also did clerical work and other necessary tasks. Some came with considerable experience in dietetics or nutrition, while others had serve welfare organizations in the United States prior to the war. A specialized group that emerged from the needs of the Army in 1918 was the “Hello Girls,” who trained as telephone operators for the Army Signal Corps. Thousands applied for these positions, and several hundred completed the necessary training and served overseas in this capacity.2

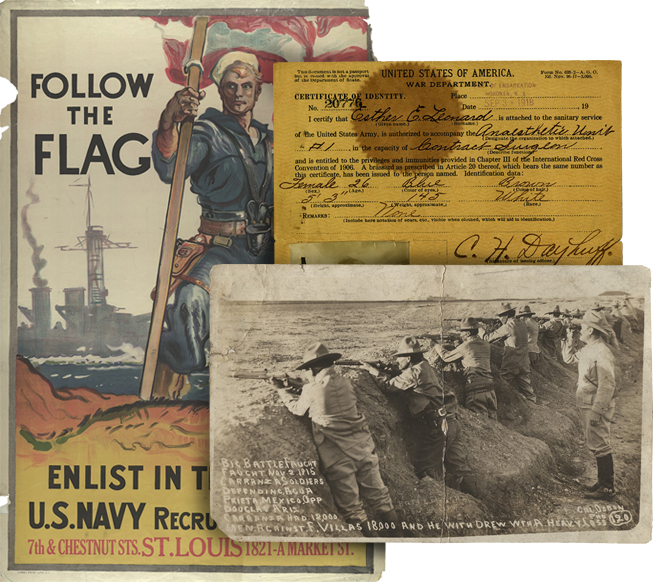

Many women also travelled to France and Italy with American forces in order to serve in hospitals as doctors, nurses, orderlies, aides, and drivers. Ernest Hemingway’s well-known novel, A Farewell to Arms, discusses one such nurse working in Italy, but women performed a number of roles in the medical field, including serving as occupational and physical therapists. While some worked for other charities or foreign medical missions, the majority of US women in medical occupations during the war worked under the auspices of the American Red Cross and its affiliates. The Army needed doctors, so a number of trained female physicians worked as contract surgeons for the US Army. Esther E. Leonard, a 26-year-old woman who finished her medical training in St. Louis just as the United States was entering the war, was hired as an anesthetist (contract surgeon) for the Army in 1918. Leonard worked first for a hospital stateside, but she was quickly transferred to an AEF unit in France, where she remained into the immediate postwar period. Leonard describes the shock of what she saw in a brief poem from October 1918, noting that she is glad to relieve men of their “Chamber of Horrors” with soothing drugs, such as morphine, cocaine, and ether.3 For Leonard, as well as many other doctors, the horrors they saw only reinforced the important work they were doing for their nation and for humanity.

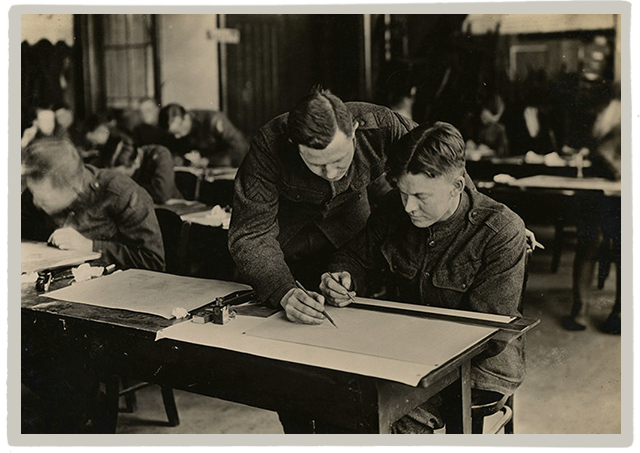

Women also trained as nurses, aides, and drivers for units such as the American Women’s Hospital services.4 Some women worked for foreign hospitals prior to the US entry into the war, but after 1917, the largest number of nurses were employed by the Army Nurse Corps. Roughly ten thousand women served overseas in this organization during and immediately after the war.5 One interesting area where women were recruited for service was in the emerging job known as a “Reconstruction Aide.” This was a program where women learned to care for soldiers recuperating from war injuries. The RAs specialized in massage, physical therapy, occupational therapy, and speech therapy. These women used handicrafts to help men heal, so they taught weaving, woodworking, carving, and sewing to help men relearn their motor skills.6

For women without medical training, another possibility was to serve was in canteens that were established for US soldiers behind the fronts. These canteens were sponsored and built by voluntary organizations hoping to provide wholesome recreation for the men. Female entertainers made the circuit of these recreation huts, performing popular songs, dancing with soldiers, and doing theatrical pieces. In addition, organizations recruited all-American girls to serve food, play board games, maintain libraries, write letters, and otherwise distract the soldiers in “good” ways. The most popular of these organizations was the YMCA, which sponsored facilities for US soldiers. While the YMCA and other agencies technically served both white and black troops, their facilities were segregated and few black women were approved for service overseas. So while nearly six thousand women served in the canteen industry, only a handful were African-American.7 Most of the American canteen workers served late in the war in 1918 or during the armistice period when large numbers of soldiers awaited demobilization.

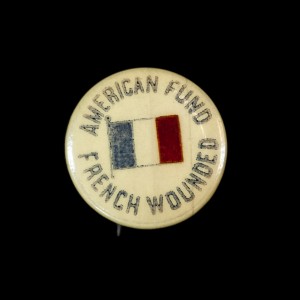

M. Keeley was one such worker who arrived in France right at the time of the armistice. As a young woman YMCA worker from Missouri, she reported that the women who served in the Y huts worked hard. She describes a variety of tasks from cooking, cleaning, and hosting events to the heart-breaking tasks of talking with soldiers who were homesick, ill or mourning. Keeley also points to one of the eye-opening parts of women’s overseas service, their exposure to a rougher life. She is horrified by some of the soldiers’ profanity and even before leaving the United States for France, she notes the shocking sight of young women smoking.8 Another volunteer driver for the American Fund for French Wounded, Amy Owen Bradley, remembered the way the French people stared at her. Few had seen a uniformed woman driving a car!9 For women serving overseas, the experience could be exhilarating and frightening at the same time. They felt a sense of purpose and service to nation, but they also comment on the adventure of their lives – dancing, meeting men, seeing the world. For many it changed their outlooks.

Early in the war, even before the United States entered, some women served in Europe in war relief and aid roles. By 1918, the numbers of females engaged in such aid had risen to several thousand. The war relief took a variety of forms, from the creation of maternity hospitals for French civilians to work with refugee populations to the rebuilding of devastated villages. Some women even worked among enemy prisoners of war. For instance, the National World War I Museum in Kansas City possesses a lovely thank-you banner created for female relief worker, Eleanor McGee, which was signed in German by POWs in France.10 Two of the major war relief societies that relief on female labor were the American Fund for French Wounded, founded by Anne Morgan the wealthy daughter of banker J. P. Morgan, and the American Friends Service Committee (Quaker). One such woman in Missouri, Laura Birkhead, found herself doing work with Belgian and French refugees in the latter part of the war. After corresponding with a friend in Neosho, Birkhead collected materials from a club of Neosho women who sent clothing and other needed supplies to Birkhead for distribution to civilians in need.11 Such impromptu charitable endeavors were not unusual in the First World War, and women spearheaded small projects to help war victims well into the 1920s.

CONCLUSION

Women employed in all varieties of war work found themselves still in Europe after the armistice. Auxiliaries remained in France into 1919, and for the war relief societies, the end of the war brought even more opportunity and need for volunteers. Quaker relief, for instance, continued well into the interwar period, and more women traveled to Europe to help feed children in countries devastated by war. Medical personnel also remained to work with soldiers needing rehabilitation. Some women found themselves travelling overseas after the war for a sadder service, namely to visit the memorials, graves, and sites of conflict where their sons, brothers, husbands, and fathers died. The Gold Star Mothers, an organization for the women who had “sacrificed” their sons, organized pilgrimages for women to visit the battlefields and to mourn their dead.12

Political and military figures as well as the popular media celebrated women’s wartime service, and several women received commendations or citations for heroism. Helen Day, a Red Cross canteen worker and hospital aid from St. Louis, was cited for bravery (along with the rest of her unit in France), when they experienced an enemy bombardment. Other US medical personnel received foreign honors, especially from US allies such as France, Belgium, and Britain. A few women died from enemy action, but most deaths of women in service were attributed to disease, especially during the influenza epidemic. Yet despite women’s overseas actions, their heroism, and the celebration in the media of their work, most authorities continued to view women’s wartime service as an aberration. Women who returned were urged to settle down and return to their domestic sphere.

What the First World War did for women is hard to put into concrete terms. Certainly the war provided new opportunities for women to serve the nation, and the creation of female veteran’s organizations speak to this function. The war also helped legitimize the women’s suffrage legislation making it through the ratification process in 1918, as men vocally supported the important part women had taken in the war. Women’s vote on equal terms with men helped validate their claim to citizenship in the nation. Finally, the war established a precedent—a test, if you will—of women’s capacity to serve overseas. Their success in World War I meant that a new generation of women would be called to work for the wartime nation in even larger numbers in the Second World War.

1Susan Zeiger, In Uncle Sam’s Service: Women Workers with the American Expeditionary Force, 1917-1919 (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1999), 2.

2Lettie Gavin, American Women in World War I: They Also Served (Boulder: University Press of Colorado, 1997), 78-79.

3Esther E. Leonard collection, Missouri Over There, http://missourioverthere.blogspot.com/

4Kimberly Jensen, Mobilizing Minerva: American Women in the First World War (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2008), 107-113.

5Zeiger, In Uncle Sam’s Service, 107.

6Tammy M. Proctor, Civilians in a World at War, 1914-1918 (New York: New York University Press, 2010), 153-154.

7Zeiger, In Uncle Sam’s Service, 52-53.

8M. Keeley collection, Missouri Over There, http://missourioverthere.blogspot.com/

9Amy Own Bradley, Back of the Front in France (Boston: Butterfield, 1918), 4.

10Eleanor McGee collection, Missouri Over There, http://missourioverthere.blogspot.com/

11Laura Birkhead collection, Missouri Over There, http://missourioverthere.blogspot.com/

12The National World War I Museum in Kansas City at Liberty Memorial holds an excellent collection of materials on the Missouri and other Midwestern women who belonged to the Gold Star Mothers and who went on pilgrimage.

13Clipping from St. Louis Post-Dispatch, Helen Day collection, Missouri Over There, http://missourioverthere.blogspot.com/

Author

Tammy M. Proctor

Tammy M. Proctor is Department Head and Professor of History at Utah State University in L…

Learn more