The German American Experience in Missouri during World War I

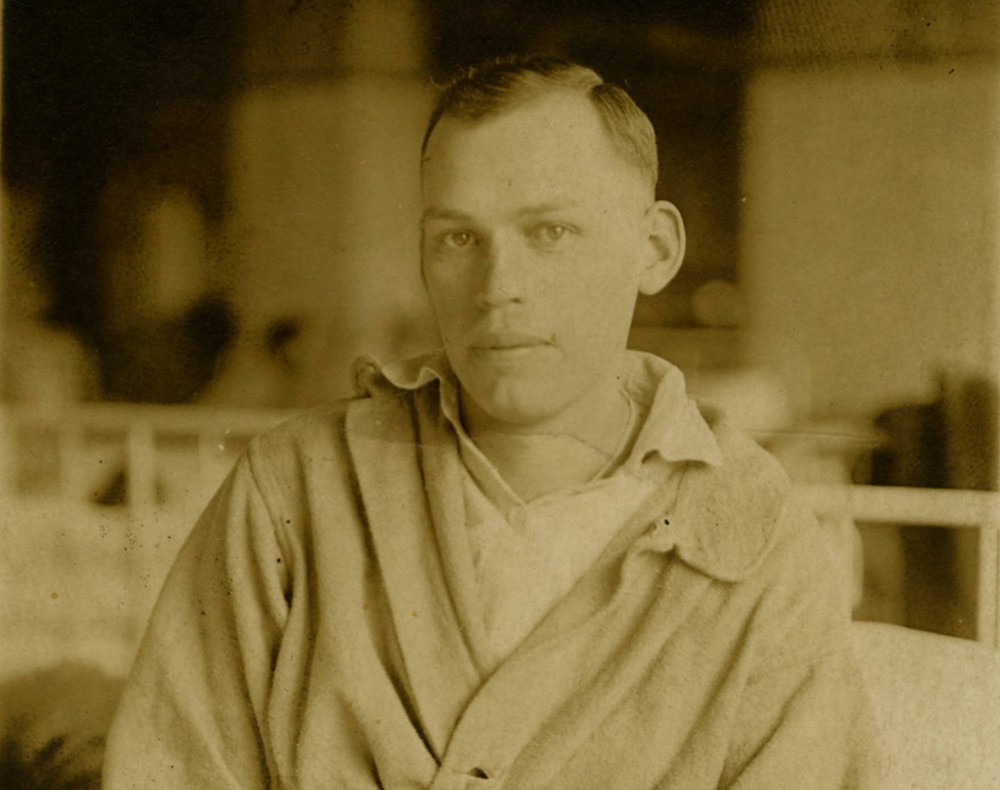

Photograph of Hugo Schroeder - n.d.

Image courtesy of Velma Schroeder Rohan

During the Great War, German Americans and those of German or Austrian extraction, felt pressured to demonstrate their loyalty to the United States owing to national, state, and local mobilization efforts. Men volunteered for active duty, registered with the Selective Service, served when drafted, or if too old participated in the Home Guard. Families invested in Liberty Bonds, purchased War Savings Stamps, conserved food, and supported the Red Cross. Most did so to express their heartfelt patriotism; others intended to appear loyal to divert attention from their ethnicity; and some resented the war’s and government’s interference in their daily lives.1

Federal legislation directly impacted many German Americans. Immigrants from Germany and Austria who had not yet become naturalized citizens were defined as alien enemies and had to register with federal authorities. In Missouri, 5,890 men and 2,684 women registered, including several American-born women who had married German-born men and, according to the 1907 Naturalization Law, had acquired the nationality of their husbands.2

The Trading-with-the Enemy Act required that editors of foreign language newspapers, including the Westliche Post in St. Louis and Missouri Volksfreund in Jefferson City, file with local postmasters translations of articles related to the national government and war. Editors who refused lost their second-class mailing privileges and in several instances had to close German-language newspapers, including the Osage County Volksblatt and the Sedalia Journal.3

The Trading-with-the-Enemy Act also gave the alien property custodian the authority to confiscate property belonging to any German citizen or person residing in Germany. The custodian seized several businesses in St. Louis and took partial ownership of companies in St. Joseph and Kansas City.4 The Bush family from St. Louis personally experienced this legislation. Clara and Wilhelmine, the American-born daughters of Adolphus Busch, had married German citizens and lived in Germany. The custodian confiscated both their inheritances, about two-eighths of the entire Busch estate. Eliza “Lilly” Busch, the widow of Adolphus Busch, had visited her daughters in 1914 and decided to remain there in case one of them should become a widow. The custodian took possession of her inherited estate, consisting of one-eighth stock ownership of the Brewery because her actions in Germany, including donating money to hospitals and turning her home into a rehabilitation center for German soldiers, fit the interpretation of aiding and abetting the enemy. Mrs. Busch regained her property in December 1918 when she returned to the US.5

The 1917 Espionage Act, outlawing any actions that could interfere with the military, and the 1918 Sedition Act, controlling dissent through limitation of the freedom of speech, led to the arrest of several German Americans who expressed pro-German or anti-American thoughts.6 Punishment, however, was not universal in severity. August Heidbreder, a wealthy farmer in Gasconade County received a $100 fine for his suggestion that President Wilson should be stuffed into a canon and shot out to sea,7 and August Weist, the deputy collector for St. Louis, had to pay a $200 fine for allegedly stating “Our boys have no damned business being over there….The government has no damned business conscripting our boys over here.”8 By contrast, August Scheuring, a German-born resident in St. Louis, received a lengthy prison sentence at Fort Leavenworth because while traveling in a streetcar and sitting in front of uniformed soldiers he allegedly stated that “the Kaiser will win the war.”9

State and county institutions responsible for mobilization had an even greater impact on the lives of German Americans because they defined disloyalty in contexts of personal relationships and decided how to punish unpatriotic individuals. The Missouri legislature had ended its biennial session in April 1917 and would not meet again until January 1919. Governor Frederick D. Gardner and the Missouri Council of Defense, appointed by him upon the instructions of the National Council of Defense, were in charge of mobilizing the state.10 Gardner used his appeal for “one people, one sentiment, and one flag; ready to cooperate, ready to sacrifice, ready to suffer” to instill patriotism but also defined disloyalty by declaring in April 1917 that “this is no time for slackers…it is our duty to drive them out and brand them as traitors.”11 One year later he asserted that all pro-Germans were German spies and threatened to establish martial law in Missouri if he discovered “these traitorous wretches.”12 Both the governor and the state council instructed county and township councils that they held the responsibility to meet mobilization quotas and control dissent.13

This local enforcement power expressed itself in various forms. In Osage County, the draft board rescinded Paul Paulsmeyer’s exemption from military service for physical disability because he had made derogatory remarks about Red Cross volunteers.14 In Jefferson City, a “Committee of citizens” gave Fritz Monat, a German-born Socialist, a public flogging and forced him to kiss the flag because he had made pro-German remarks and his association with militant labor unions threatened to destabilize the city’s labor relations.15 In Gasconade County, “intensely and aggressively patriotic” German Americans, fearful that the county acquire the “slacker” label, coerced fellow German speakers to more enthusiastically support the war, increase their purchase of liberty bonds, and keep any critical thoughts to themselves. They also supported the renaming of the small town of Potsdam to its more patriotic name, Pershing.16

Several communities attempted to outlaw the use of German. The Cass and Linn County Councils of Defense banned the use of German on the telephone.17 The Franklin County Council of Defense resolved that conversing in German in public would be “unwise and unpatriotic.” The St. Louis Republic agitated for an end to the German-language press and initiated a city-wide campaign to change street names from offensive-sounding German to acceptable American names.18 Such local demands had state-wide impact because the State Council reacted in August 1918 by announcing a resolution that strongly encouraged all Missourians to speak English.19

Coercive pressures through national legislation, state organizations, and local institutions created suspicions of all things German during World War I and led in some cases to super-patriotic activity but in other cases to peaceful treatment of suspected disloyals. Less than enthusiastic individuals, whom zealous war supporters mistrusted, often diverted attention from themselves by harassing others. German Americans, who desired to impress their own sense of patriotism on their neighbors, reported fellow German Americans to the authorities. Physical violence, however, was limited to individuals who flaunted their support for Germany.

1 For a more detailed study see Petra DeWitt, Degrees of Allegiance: Harassment and Loyalty in Missouri’s German-American Community during World War I (Athens: Ohio University Press, 2012).

2 “Germans in U. S Must Register Week of Feb. 4” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, December 31, 1917; “Zur Registrierung feindlicher Ausländer,” Westliche Post, January 1, 1918; “Frauen Registrierung,” Westliche Post, June 1, 1918; “German Enemy Alien Women Must Register,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, June 12, 1918; “2684 Frauen registriert,” Westliche Post, June 27, 1918. Jörg Nagler, Nationale Minoritäten im Krieg: Feindlich Ausländer und die amerikanische Heimatfront während des Ersten Weltkriegs (Hamburg: Hamburger Edition HIS Verlagsbes. mbH, 2000), 262. Nancy F. Cott, “Marriage and Women’s Citizenship in the United States, 1830-1934,” American Historical Review 103 (December 1998): 1461-64.

3 David M. Kennedy, Over Here: The First World War and American Society (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1980), 75-77. “Abschieds-Ankündigung!” Sedalia Journal, May 10, 1917. “Zum Abschied,” Osage County Volksblatt, July 19, 1917.

4 Alien Property Custodian Report, (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1919; reprint, New York: Arno Press, 1977), 7, 310, 318, 336, 353; ”Holders of Alien Property Ordered to Report By Dec. 5,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, December 2, 1917; “Survey Ordered of Alien Property Owners in State,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, June 2, 1918.

5 “Questions Status of German Busch Heirs,” St. Louis Post Dispatch, December 13, 1917; “U. S. Seizes Vast Estate of Mrs. Busch,” and “U. S. Now in Control of Three-Eighths of Vast Busch Fortune,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, June 18, 1918; Alien Property Custodian Report, 473.

6 Kennedy, Over Here, 75-77.

7 “A Bland Man Nabbed,” Unterrified Democrat, May 31, 1917. “Local and Personal,” Unterrified Democrat, July 5, 1917.

8 United States v. August Weist, Docket No. 6911, Record Group 21, Records of the U. S. District Court, Eastern District of Missouri, Criminal Cases, 1864-1966, National Archives, Central Plains Region, Kansas City, Missouri (hereinafter cited as RG 21, District Court, Criminal Cases, NA KC).

9 United States v. August Scheuring, Docket No. 6661, RG 21, District Court, Criminal Cases, NA, KC; Inmate 12554, Box 486, Record Group 129, Leavenworth, Federal Inmate Files, NA, KC.

10 National Council of Defense Bulletin 8, p. 21, folder 202; “Organization and Work of Councils of Defense,” folder 240, both in Collection 2797, Missouri Council of Defense Papers, Western Historical Manuscript Collection, University of Missouri-Columbia (hereinafter cited as MCDP, WHMC). Final Report of the Missouri Council of Defense, 1917-19 (St. Louis: Con. P. Curran Printing Co., 1919), 8. Lawrence O. Christensen, “Missouri’s Response to World War I: The Missouri Council of Defense,” Midwest Review 12 (1990): 35

11 “Great St. Louis Meeting Proclaims Loyalty to Nation,” St. Louis Republic, April 6, 1917. Floyd C. Shoemaker, “Missouri and the War: Sixth Article,” Missouri Historical Review 13 (July 1919): 320.

12 “Pro-Germans Classed as Spies by Gardner, Warned to Keep out of Missouri,” St. Louis Republic, April 8, 1918.

13 “County Councils to be Supreme,” Missouri On Guard 1 (July 1917): 2.

14 J. Richard Garstang to F. B. Mumford, 5 June 1918, folder 1044; J. Richard Garstang to W. F. Saunders, 8 July 1918, folder 293, MCDP, WHMC. Paulsmeyer, Paul J., Military Service Record World War I, Soldiers Database: War of 1812 – World War I, Missouri Archives, Online Database, http://www.sos.mo.gov/archives/soldiers/ (accessed 6 June 2005).

15 “Mob Flays Pro-German; Forces Him to Kiss Flag in the Jefferson Theater,” Daily Capital News (Jefferson City), April 6, 1918; “Monat Held Pending Action of Officials,” Daily Post (Jefferson City), April 6, 1918; “I.W.W. Agitator Saved from Angry Crowd Last Night by City Police,” Daily Capital News, February 23, 1918; “Disloyal Agitator Demented, is Belief,” Daily Post, February 23, 1918.

16 Robert A. Glenn, “Report on Gasconade County Council of Defense,” 14 May 1918, folder 880, MCDP, WHMC. Joe Welschmeyer, “Down at Pershing,” Osage County Observer (Linn), September 26, 1979; and Joe Welschmeyer, “From Potsdam to ‘Pfoersching: Pershing’s History Mirrors Germany’s,” Unterrified Democrat (Linn), September 9, 1998.

17 J. F. Mermoud to William F. Saunders, 7 June 1918, folder 373c; W. P. Kimberlin to W. F. Saunders, 11 July 1918, folder 373d; W. F. Saunders to Elliott Dunlap Smith, 6 July 1918, folder 373d; all in MCDP, WHMC. “News from Adjoining Counties,” Advertiser-Courier (Hermann), June 12, 1918.

18 “Movement is Started in St. Louis to Suppress Hun-Language Press,” St. Louis Republic, April 27, 1918; “German Names,” St. Louis Republic, April 10, 1917; “Make St. Louis 100 Percent American,” St. Louis Republic, April 10, 1918.

19 Minutes of the Meeting of the Missouri Council of Defense Held in Cape Girardeau, July 12, 1918, folder 499 and 502; MCDP, WHMC. “Abolition of German Language is Indorsed [sic],” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, July 14, 1918.

Author

Petra DeWitt

Petra DeWitt is an assistant professor in the Department of History and Political Science…

Learn more