The Coming of the War

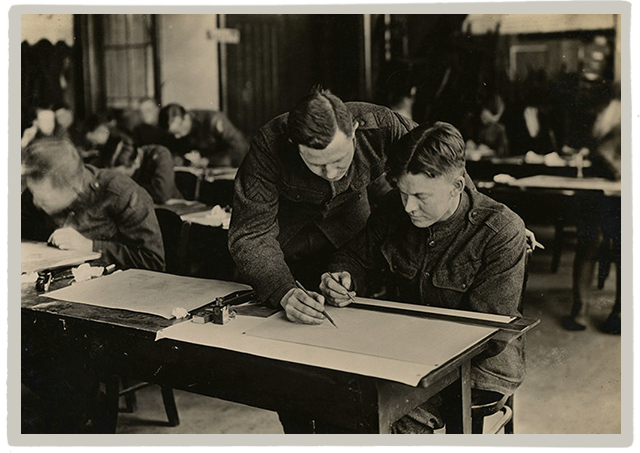

Missouri draft men - n.d.

What we now call the First World War might well have been known to history as the Third Balkan War. The assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand in Sarajevo on June 28, 1914 by a young Serbian patriot struck most Europeans in 1914 as a Balkan problem that hardly touched their lives. In the summer of 1914 few Europeans foresaw a war and fewer still wanted one. The vast majority of them expected that the assassination of the archduke would soon pass as had so many previous crises in Europe.

This feeling of security changed on July 23, 1914. On that day, Austria-Hungary issued an ultimatum to Serbia, whose leaders they believed had been behind the assassination plot. The ultimatum demanded that Serbia meet a series of conditions within 48 hours or Austria-Hungary would announce that a state of war existed between it and Serbia. Austria-Hungary’s decision to push a minor crisis far beyond what was normal or necessary changed the rules of the game. The ultimatum demanded too much of Serbia and its 48-hour window sped up the timetable deliberately in order to catch the rest of the great powers flat-footed. A war started under these circumstances might well spread dangerously out of control.

We need to understand the outbreak of war in 1914 not as the result of long-standing feuds between Germany and France, Germany and Great Britain, or even Russia and Austria-Hungary. Rather, the war began because of deadly political miscalculations in Vienna and among those officials in Berlin who decided to support their Austro-Hungarian ally. Each for their own reasons, the Austro-Hungarian and German elites believed that the circumstances were favorable for trying to exploit this rather minor crisis in the hopes of reaping big rewards.

They soon realized, however, that they had badly miscalculated. Relations between Germany and Austria-Hungary had in fact declined in the years before the war, mainly because of Germany’s discovery of a spy ring at the highest levels of the Austro-Hungarian high command. Consequently, the war plans of the two allies remained dangerously disconnected from one another. Seemingly without realizing the overall impact of their collective decisions, the Germans had planned to send seven of their eight field armies to the west in the event of war while Austria-Hungary planned to send its field armies to the south to punish Serbia for its alleged role in the assassination plot.

Into this already volatile mix stepped Russia. Russian leaders, too, miscalculated. They had hoped that by mobilizing their armies on their border with Austria-Hungary they could either gain something for themselves out of this crisis or at least force the Austro-Hungarians to modify their aggressive behavior. Instead, the Russian mobilization frightened the German government and the German people. The German government now knew that it, too, must mobilize its armed forces, but only a few knew that the German war plan called for an invasion of France and Belgium, not Russia. Long assuming that a war with either France or Russia meant war with both (the two had been allies since 1894, although many people in France disliked the alliance), the Germans had hard-wired a war plan that sought to defeat France first.

More political and military miscalculations ensued. The Germans had assumed that they could defeat France quickly enough to move their armies east and meet the Russians. But the Russians, having mobilized first and with surprising efficiency, soon proved to be a real threat to German security. Austro-Hungarian armies having headed south, there was no serious plan in place to deal with the Russians. German assumptions that Great Britain would remain neutral also faltered, as the British saw the need to honor their military commitments to France and to prevent the Germans from dominating the continental side of the English Channel coastline.

All of these miscalculations confused and bewildered the European people, few of whom could figure out how the shooting of an obscure Austrian nobleman had led to this disaster. They did, however, know that a foreign army now threatened their nation and their community. They could all believe, moreover, that their states had acted in self-defense. Thus they could (and did) see the actions of their governments as defensive and, therefore, just.

Author

Michael S. Neiberg

Michael S. Neiberg is the Henry L. Stimson Chair of History in the Department of National…

Learn more