American Doughboys Overseas

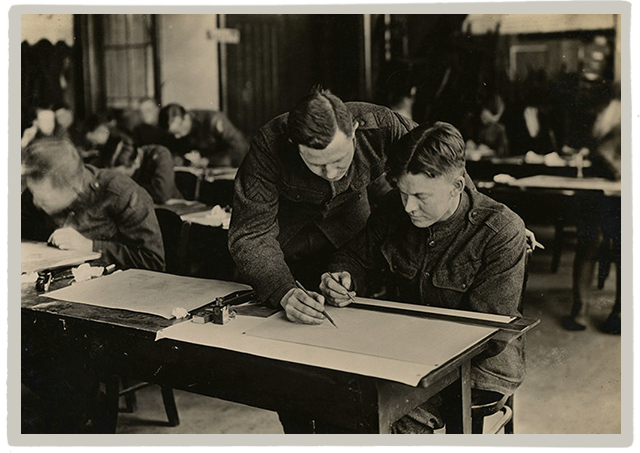

Soldiers enjoying a snack - n.d.

The United States entered World War I in April 1917, two and a half years after the war started. Having made few preparations beforehand, it took the nation nearly a year to raise, train, and transport an expeditionary force overseas. American soldiers only fought along the Western Front in 1918, a period when the trench deadlock broke open and a war of movement resumed. Doughboys certainly spent a fair amount of time in the trenches, but sustaining momentum in battle proved the greater challenge during the fall 1918 when most American soldiers entered the front lines.

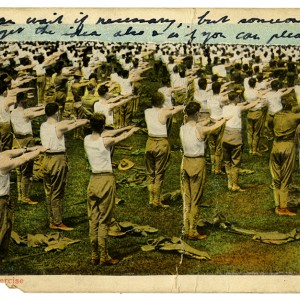

The nation relied primarily on conscription to raise the wartime force, although Regular Army and National Guard units accepted volunteers until December 1917. The enlisted population reflected the multi-ethnic and racial composition of the American population. One in ten was black; one in five foreign-born. Most divisions contained men from neighboring states, but the 42nd Division (nicknamed the Rainbow Division) drew together National Guard units from 26 states and the District of Columbia. The unit epitomized the government’s hope that military service would unify men from diverse backgrounds, erasing class and ethnic differences. This “melting pot” ideal did not extend to African Americans who served in segregated units. “Black is not a color of the rainbow,” African American soldiers of the 15th New York Infantry Regiment bitterly told each other when they failed to win a place in the 42nd Division.

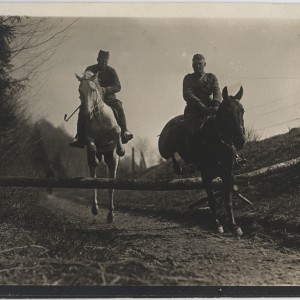

Soldiers worked and fought in tremendously diverse circumstances. Combat units contained infantry, artillery, communication specialists, engineers, clerks, cooks, and medics. These units were sustained in the field by non-combatant troops who labored to construct roads, repair railroads, and furnish units with needed supplies. A soldier’s unit and his assigned duties, therefore, dramatically shaped how he spent his time overseas.

For most American soldiers, combatant and non-combatant alike, this was their first experience in France. Training and marching to new locations absorbed a tremendous amount of time. Doughboys nonetheless found time to visit French cafes and towns. Encounters with the French created some friction, especially when U.S. troops drank too much or accused French civilians of over-charging them. For African Americans, however, the experience of living overseas was liberating. The French welcomed African Americans into their homes and restaurants, and many developed friendships with French women. The apparent lack of racial prejudice convinced many black soldiers that France offered a model democracy for the United States to emulate.

Many American doughboys received their baptism of fire by training in quiet areas with Allied troops to learn the basics of trench warfare. Several divisions fought in French and British-commanded operations to halt the German spring offensives that nearly reached Paris. Even more participated in the summer counter-offensives that pushed the Germans back to the original trench line. By the fall, the American Expeditionary Forces (AEF) had taken over its own sector of the Western Front and began preparations for the American-led St. Mihiel offensive (September 12-16, 1918).

The St. Mihiel offensive successfully reduced a salient in the lines that made the Allies vulnerable to German attack. Corporal Rudolph Forderhase, a member of the 89th Division aptly summed up his experience waiting to “go over the top” from the trenches to begin the assault. “A million artillery shells were fired in the four hours, from 1 am to 5 am, in support of the attack by the Infantry of the 1st, 2nd, 42nd, 89th, and 90th Divisions. It is hard to describe the awesome din of the guns, the muzzle flashes, the roar of the shells passing overhead, the crashing report when they exploded on enemy positions,” he recalled. 1

There was no time to celebrate the quick victory. The AEF had just two weeks to re-locate sixty miles and prepare for another massive assault. The Meuse-Argonne campaign lasted for 47 days and involved 1.2 million men, the largest battle in American history. The offensive was the American contribution to a synchronized Allied attack along the entire Western Front that began in late September and lasted until the armistice on November 11, 1918.

General John J. Pershing’s decision to use his best trained units at St. Mihiel proved costly since these divisions (including the 42nd and 89th Division) had to rest and re-group before taking part in the Meuse-Argonne offensive. Five of the nine divisions that opened the Meuse-Argonne campaign were fighting for the first time. Inexperience proved costly. The Americans had little practice coordinating infantry and artillery, or incorporating air power into advances. Imperfectly functioning supply lines also hampered progress, as huge traffic jams and congestion developed in the rear.

Breakdowns in communication and unit cohesion resulted in horrendous casualties for the 35th Division. Post-combat investigations blamed poor discipline and lack of training for the division’s difficulties, but commended the troops for acts of individual bravery. Better training would result in an improved performance, investigators concluded. The fate of the 92nd Division, an African American unit, was markedly different. Like the 35th Division, components of the 92nd Division faltered during its first sustained foray into battle. AEF officials, however, castigated the division’s black officers and replaced most of them with white officers. The postwar army subsequently cited this poor performance to argue that African Americans were racially inferior and unsuited for command.

At the height of the Meuse-Argonne campaign officials estimated that 100,000 stragglers had lost contact with their units, probably intentionally. Pershing viewed these alarming figures as evidence of an under-trained army forced by circumstances to fight before it was ready. However many soldiers left the lines to seek treatment for influenza, not to avoid combat. The Meuse-Argonne campaign coincided with the second deadly wave of the Spanish Influenza pandemic. The influenza virus ultimately proved as deadly as German bullets for American doughboys.

Corporal Forderhase of the 89th Division fought until the very last moments of the war on November 11, 1918. “I took a look at the cheap wrist watch that I had been wearing. It had stopped at eleven o’clock and I never did get it to run again,” he later recalled. That was the exact time when the armistice began, an hour engraved in the memories of all surviving doughboys. 2

1 Corporal Rudolph Forderhase, 356th Infantry, 89th Division, in American Voices of World War I: Primary Source Documents, 1917-1920, ed. Martin Marix Evans (Chicago: Fitzroy Dearborn Publishers, 2001), 122.

2 Forderhase, American Voices of World War I: Primary Source Documents, 1917-1920, 160.

Author

Jennifer D. Keene

Jennifer D. Keene is Professor of History and Chair of the History Department at Chapman U…

Learn more

Related Articles

Related Collections

Ball, Hampton B. Papers

Hampton B. Ball served in the 1st Battalion, 326th Infantry, 82nd Division…

Barkley, John Lewis Collection

John Lewis Barkley was inducted into the army at Warrensburg, Mo. on Septem…

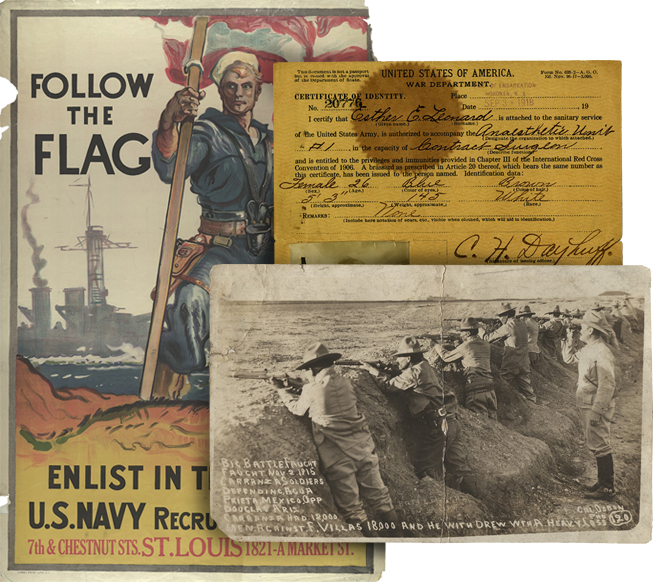

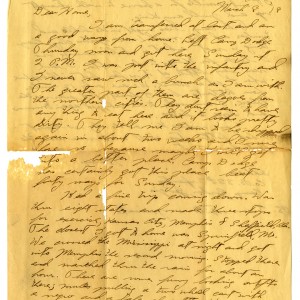

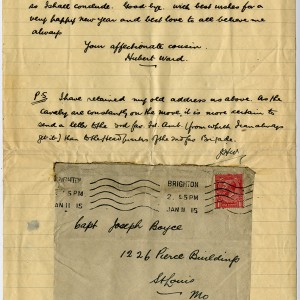

Boyce, Joseph Collection

Hubert Ward was a captain in the Royal Army Medical Corps and served with t…

Brady, Robert Kirk Collection

Capt. Robert Kirk Brady from Richmond, Mo. served in Company G, 140th Infan…

Cookingham, L. Perry Collection

Laurie Perry Cookingham served in France and Germany with the 310th Field S…

Hockaday, James Kellogg Burnham Collection

1st Lt. James Kellogg Burnham Hockaday enlisted in Kansas City, Mo. on Augu…

Smith, Richard Thompson Collection

Richard T. Smith joined Company A of the Signal Corps, Missouri National Gu…

Vonland, George Collection

George O. Vonland, of St. Louis served in Company H, 138th Infantry, 35th D…

Westover, John G. Papers

Owen Glendower (Glen) Tudor grew up in St. Louis. On June 28, 1917 he enli…