African Americans and World War I

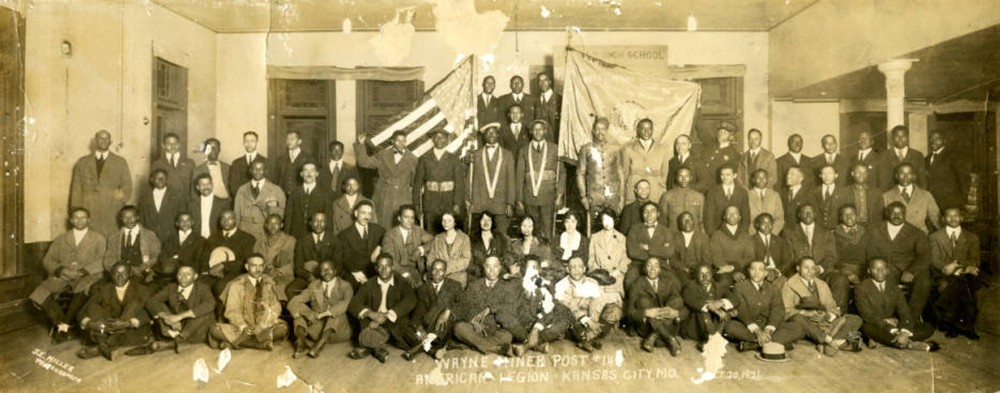

Photograph of Wayne Miner, American Legion Post #149 - October 20,1921

Image courtesy of Black Archives of Mid-America

President Woodrow Wilson’s proclamation that the United States was fighting “to make the world safe for democracy” rang hollow for many African Americans. Wilson had already disappointed civil rights leaders by allowing federal agencies to re-segregate their offices and by endorsing the white supremacist message of the controversial film Birth of a Nation. Determined to fight for democracy at home and abroad, many African Americans saw the war as an opportunity to press forward with their demands for equality.

During the period of neutrality most African Americans (like most Americans) remained indifferent to the larger geo-political issues surrounding the war. Many workers, however, immediately recognized the economic opportunities the war provided. The war had disrupted the flow of cheap immigrant labor to the United States just as global demand for American manufactured goods exploded. Before the war 90% of the nation’s black population lived the South. This changed once northern labor agents began recruiting black laborers in the South. The Great Migration, a movement of nearly half a million African Americans northward, transformed northern cities into thriving centers of black cultural and artistic expression. The absence of formal Jim Crow laws attracted Southern migrants to northern cities like Pittsburg, Chicago and Detroit where small, but politically potent middle-class African American communities already existed. The migration of more blacks into northern communities where they could vote helped African Americans enlarge their political power regionally and nationally.

Black middle-class groups like the Urban League helped migrants finding housing, schools, and churches. They also tried to acclimatize newly-arrived southerners to the more subtle, but equally dangerous, racial prejudices of white northerners. Migrants’ hopes of leaving the threat of lynch mobs behind in the South proved illusionary. Factory owners welcomed African Americans into their armament and meat-packing plants but white workers did not. Labor’s hostility benefited factory owners, who intentionally hired African Americans as strikebreakers to thwart white workers’ attempts to organize unions or conduct strikes. Competition over scarce housing further exacerbated racial tensions.

Racial violence therefore accompanied the Great Migration. The worst race riot of the wartime period occurred on July 2, 1917 in East St. Louis, Illinois. The riot left 30 blacks and 9 whites dead, and hundreds wounded. Appearing before a Congressional committee investigating the riot, the anti-lynching crusader Ida B. Wells-Barnett gave gruesome accounts of cold-blooded murder and torture that rivaled the prominent stories circulating of German abuses in Belgium. The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) responded by organizing the largest civil rights protest-to-date, a silent parade by 10,000 black men, women and children down Fifth Avenue in New York City. The Congressional investigation held white employers and labor leaders responsible, but 6,000 African Americans left the city anyway.

While the outcome was meager, the fact that Congress launched any investigation revealed a wartime reality: the government relied on African American participation in the wartime economy and military to successfully fight the war. Officials recognized the danger of a disaffected African American population either silently refusing to “do its bit” or even worse actively opposing the war. A vocal debate ensued among African American intellectuals over whether or not to “close ranks” (in the words of W.E.B. Du Bois) with white Americans for the duration of the war by putting their “special grievances” aside until the national crisis had passed. The passage of the Espionage and Seditions Acts made dissent difficult, however. The government initiated an intensive (and secret) domestic surveillance program that dispersed federal agents to monitor civil rights groups. The government arrested the most outspoken leaders by claiming they were under the influence of German spies and banned their publications from the mails. Many African American community leaders felt that clear demonstrations of patriotism offered a better path to civic equality than anti-war activism. African American communities throughout the nation organized to sell war bonds and conserve food.

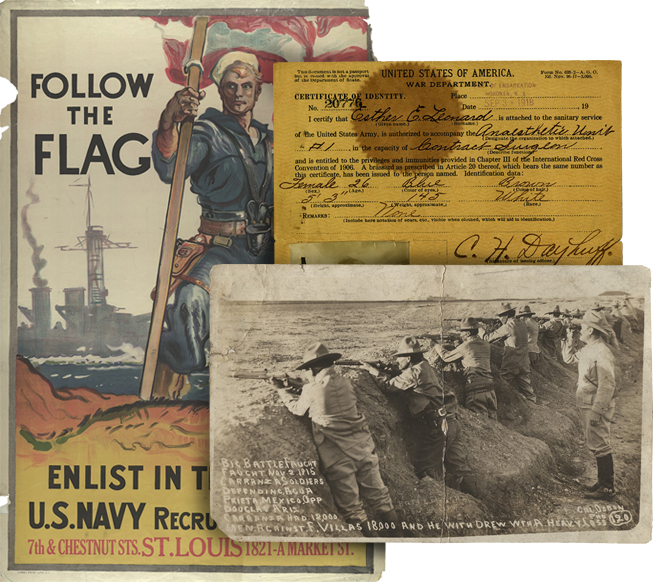

Meanwhile, African American men were entering the U.S. military. With just 4,000 slots reserved for black volunteers, over 96% of the 367,710 African Americans who served during the war were conscripted. African Americans formed 13% of the wartime army, even though they only represented 10% of the civilian population. African American men also formed a greater proportion of those who evaded the draft. Nearly one hundred thousand African American men either failed to register for the draft or neglected to report when called. Sometimes this was by choice, sometimes it was not. Southern white land-owners, for example, often withheld mailed draft notices to avoid losing their workers to the military.

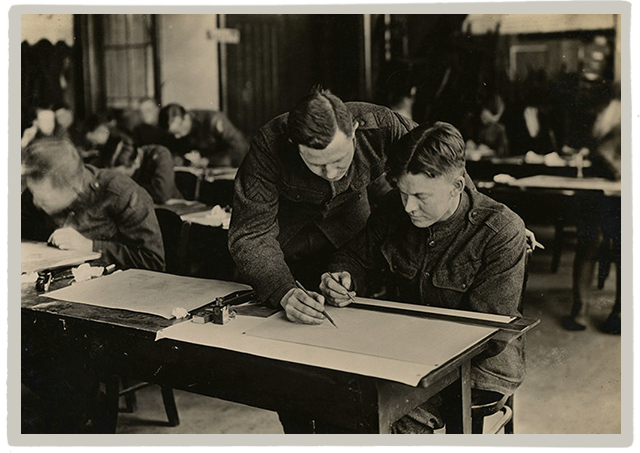

In the segregated army over 89% of African Americans were assigned to non-combatant units, mostly in Quartermaster and Engineer units. African Americans made up approximately 1/3rd of the army’s laboring units and 1/30th of its combat force. Demands for equal treatment by the NAACP and other civil rights groups led to the creation of a black officers’ training camp in Des Moines, Iowa and the appointment of Emmett Scott as a special advisor to Secretary of War Newton Baker. Racial prejudice and discrimination nonetheless remained the defining characteristic of military service for African American soldiers.

Forty-thousand African Americans served in two combatant units, the 92nd Division and the provisional 93rd Division. The latter consisted of four infantry regiments that spent most of the war embedded in the French Army. These two divisions had completely different experiences. The 92nd was reviled by white American commanders while French officials honored and celebrated the achievements of the 93rd. The positive interactions between African American servicemen and French civilians offered yet another stark challenge to Wilson’s claims that American-style democracy offered a model for the world to follow.

African Americans did not have long to celebrate the end of combat on November 11, 1918. The summer of 1919 became known as the “Red Summer” for the wave of assaults that engulfed black communities nationwide. Southern communities mobilized to prevent black veterans from challenging the racial status quo, leading to a dramatic, but short-lived, spike in lynchings. Race rioting also rocked Chicago and Washington, D.C., but something important had changed since East St. Louis.

In 1919 African American communities collectively embraced an ethos of fighting back, with returning veterans leading the way. Besides fighting back in the streets, ex-servicemen poured into the NAACP and the more militant United Negro Improvement Association. Community wartime committees transformed themselves into new chapters of the NAACP, further bolstering the strength and reach of the civil rights movement. Abandoning the gradualist approach of older activists, the World War I generation pioneered new legal and protest strategies with the goal of ending racial discrimination immediately. There were many setbacks still to come, but in World War I the African American community took crucial first steps towards building the successful civil rights movement of the twentieth century.

Author

Jennifer D. Keene

Jennifer D. Keene is Professor of History and Chair of the History Department at Chapman U…

Learn more

Related Articles

Related Collections

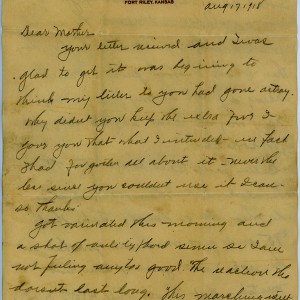

Davis, James Robert Collection

James Robert Davis lived in Marshall, Mo. when he was inducted into the arm…

Peters, William Collection

William Peters was the city photographer for St. Louis from 1916-1920. Und…