The Great War in American Memory

Photograph of the 129th Field Artillery on Parade in Kansas City - n.d.

Image courtesy of the National World War I Museum

Casualties: Bringing The Dead Back Home

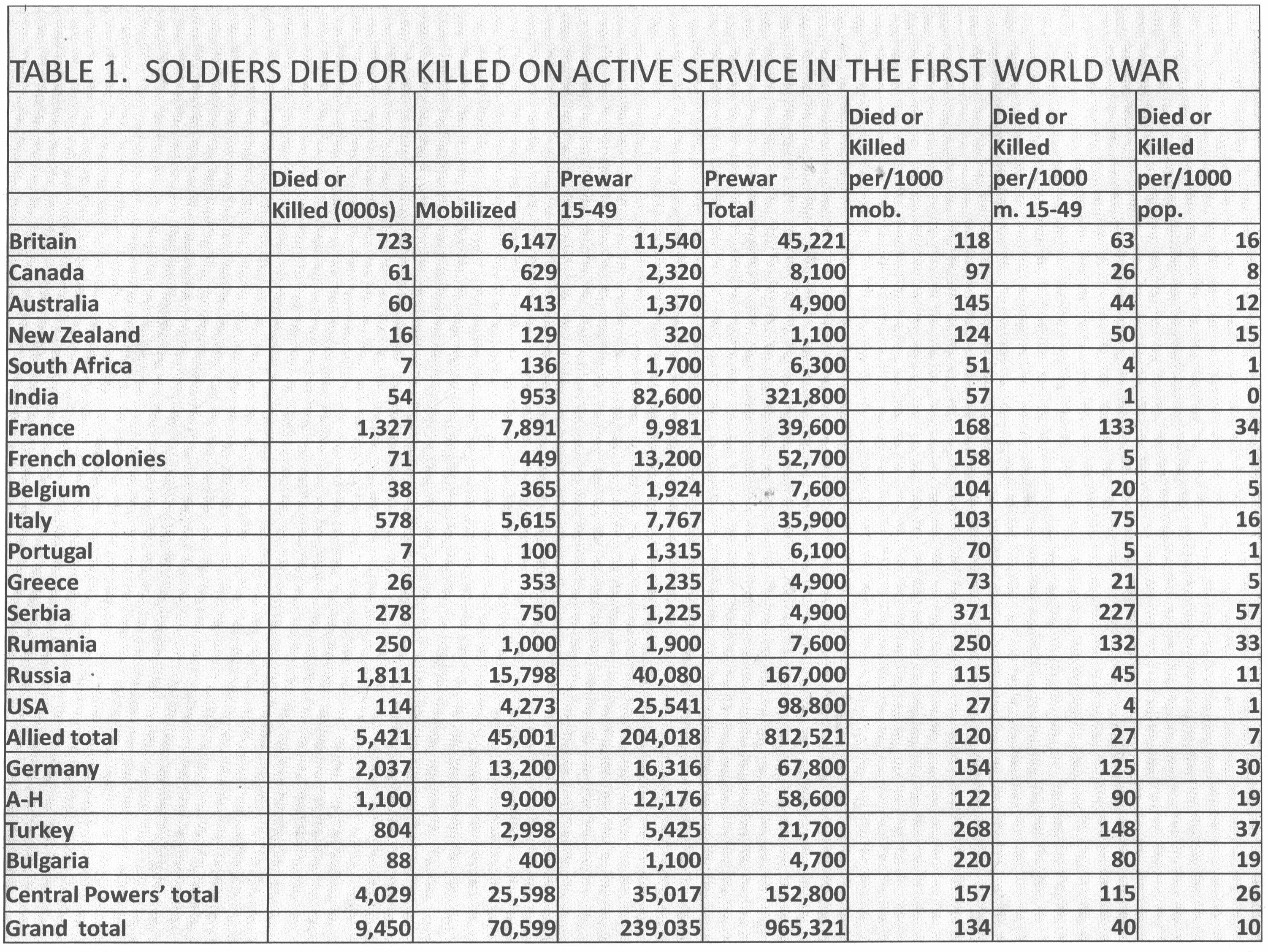

The place of the 1914-18 conflict in American memorial practices and culture is modest, and contrasts sharply with its central place in the memorial practices and cultures of Britain, France, Australia, New Zealand, and Canada. The primary reason for this difference is reflected in casualty statistics. The losses suffered in combat by American soldiers were dwarfed by those suffered in combat by men serving in other armies, victorious and vanquished. Roughly 55,000 American soldiers died in combat covering roughly six months in 1918. A similar number died of the Spanish influenza epidemic, but since many of them succumbed to the flu in training in the United States, their deaths have been excluded from many calculations of military losses. Even including all deaths of men in uniform, it is still evident that the United States suffered a bloody nose in the war, whereas the Great Powers suffered a massive wound, which in certain cases, has never healed. Less than 3 percent of American servicemen mobilized were killed; another 5 percent were wounded. Compare these totals to France’s 16.8 percent killed of those mobilized, or another 56.5 percent wounded. Fully three-quarters of all Frenchmen who served became casualties of war. With ten times the number of soldiers who died, the Great War has occupied for 100 years in France, a central part of national memory.

The reason why this is so is that the Great War braided together family history and national history in inextricable ways. The whole country was touched by France’s war losses, just as was the case in Britain, Canada, Australia and New Zealand. War memorials sprang up everywhere to serve as surrogate graves for those who died in a war which was not only a killing machine, but also a vanishing act. Half of all those who died in the Great War have no known graves. A war fought half a world away was simply too short and insufficiently costly in American lives to leave a mark on American culture to match that of many European states and countries of white settlement.

Rejection Of The League Of Nations

There is an additional, political, reason why the 1914-18 war, called the Great War in Europe, is not a major marker in American history or American memory. The outcome of the war was a military victory for the United States, not an ally, but an Associated Power in the victorious alliance. But it was not a political victory, in the sense that the peace settlement, fashioned in large part by the American President, Woodrow Wilson, was rejected by the United States Senate. The key dispute was constitutional. Wilson persuaded a majority, but not two-thirds, of the Senate that the Protocols of the new League of Nations would still leave the Senate as the only body entitled to authorize the dispatch of American troops to quell aggression elsewhere in the world. Without a two-thirds majority, the Peace Treaty of 1919 was not ratified. Isolationism, more a mood than a movement, signified the turning away of American attention from the European world devastated by the world war.

America’s immigration laws changed in the 1920s to protect the country from an invasion of alien ideologies, like Bolshevism. But isolationism was not the whole story, and the United States was very active in the 1920s, in particular in the sphere of financial affairs. In addition, Herbert Hoover was the author of the first foreign aid package in American history, and it was a staggering success. He fed the children of Belgium and Northern France during German occupation, and then organized a food aid program for the whole of Eastern Europe. And he made a profit doing so. His role as the enemy of world hunger will be remembered long after his time as US president between 1928 and 1932 is justly forgotten.

War Memorials And Tomb Of The Unknown Soldier

Roughly half of the families of American soldiers who died in European combat requested that their bodies be exhumed from their graves abroad and returned home. They were buried either in Arlington National Cemetery, or at a site of the family’s choosing. A minority of these sites used symbols of loss of life, including crosses, but most were figurative or allegorical, portraying soldiers marching home or mythical and frequently female symbols of virtue triumphant.

In 1921, a tomb of the Unknown Soldier was unveiled in Arlington National Cemetery, facing the Capital. The design is classical, framed by a Greek amphitheater behind it. The US Army guards the site in perpetuity, preserving the military character of the memorial, and reminding visitors that modern war destroys the remains of soldiers, so many of whom have no known grave for families to visit, but whose sacrifice is honored here. Most other war memorials are civic monuments, to which the families of the fallen processed and still process on Armistice Day, 11 November, and on Memorial day, traditionally the last Monday in May, originating from the Civil War. In these events, women enter centrally into the choreography of the memory of war, as mothers, sisters, and daughters of men who have given their lives in the service of their country. The Protestant voluntary tradition ensured that the 1914-18 conflict would be remembered in the midst of life. Highways, sports stadiums, and scholarships were funded and named for those who fought and who died in the world war.

The American Battle Monuments Commission, created in 1923, oversaw the creation of and still maintains 23 military cemeteries in which over 30,000 American soldiers who died in the Great War are interred. They use Crosses and Stars of David to signify the denomination of the soldier buried at each site, a clear exception to the rule separating church and state in the US Constitution.

In recent years, with increasing American tourism in Europe, the number of visitors to these sites has risen, though they are still much less well visited than are cemeteries in which soldiers who died in the Second World War are interred. One major exception is the removal of the body of Quentin Roosevelt, the son of President Theodore Roosevelt, a pilot killed in the First World War, to the American cemetery at Colville-sur-mer, where he now lies next to his brother, General Theodore Roosevelt, a Congressional Medal of Honor recipient, who died of a heart attack during the Normandy campaign in 1944.

Selective Memory

Remembering the Great War was primarily a white, native-born phenomenon. For the rest, there was much to hide or forget. For Irish Americans, entry into the war was a bitter pill to swallow just a year after the Irish rising of April 1916, after which Britain summarily executed the leaders of the revolt. American-born Irish patriot Eamon de Valera was spared due to his citizenship. Russian-born American Jews were relieved when the Czar fell in the spring of 1918, and when the Pale of Settlement restricting Jews to living in a defined district was abolished. But they were still wary of the nature of the new regime. German-Americans were in the most difficult position; they suffered from considerable hostility and even violence. On the quieter end of the spectrum, Hamburg Street in Brooklyn became Madison Street; countless urban and rural transformations followed suit. At the other end of the spectrum of violence, one German-born man, Robert Prager, was lynched near St Louis, and his murderers were found innocent at the subsequent trial. This is hardly the stuff of remembrance.

Similarly occluded is the story of the maltreatment of black American troops who fought against persistent prejudice and police brutality. On 23 August 1917, 156 black soldiers of the Third Battalion of the all black 24th Infantry Regiment rioted in Houston, Texas. Twenty white men were killed, and the Third Battalion was sent to New Mexico, and then to San Antonio for trial. Thirteen men were sentenced to death for murder and went to the gallows; six more were executed in 1918. In East St Louis, Illinois, race riots between newly employed black workers in a factory under government contracts, led to the deaths of eight white and at least 40 black workers. Further violence in 1919 ensured that the narrative of America fighting for democracy in the world war was restricted to whites of Anglo-Saxon, Italian, French, Belgian, and Serbian origin.

War Literature And War Film

Later generations of Americans have learned of the First World War from film and from literature. It was an accident that the outbreak of war in 1914 coincided with the emergence of the cinema as the centerpiece of mass entertainment, and that the American film industry boomed at a time when other countries were preoccupied not with film production but with war production. American exports were led by Charlie Chaplin, a displaced working-class music hall actor from London, whose face and uneven gait were known world-wide. His ‘Shoulder arms’ (1918) is a propaganda masterpiece, in which Chaplin, the downtrodden doughboy, dreams of capturing the Kaiser and ending the war. D.W. Griffith’s ‘Hearts of the world’ (1918) supported the cause, though with fewer laughs.

In the early post-war years Rex Ingram’s ‘Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse’ turned the Great War into melodrama, personified by the leading man, Rudolf Valentino. Not all American war films were romantic fluff. The Big Parade of 1925, directed by King Vidor, focused on the hardships of a G.I. who lost his leg in the war. Epic battle scenes including the spectacle of aerial combat, began before the talkies took over. ‘Wings’, directed by William A. Wellman, was one of the most successful, and won the very first Oscar for best picture of the year in 1927.

The only pacifist film to achieve commercial success in the United States was ‘All quiet on the Western Front’, the 1930 adaptation by Lewis Milestone and starring Lou Ayres. Insisting on a flat American accent for all the actors playing German soldiers, Milestone made the tale everyman’s story, and captured the mood of many other writers and artists that the war had been an exercise in futility.

This was a point of view available to Americans through the writings of soldiers and observers of the fighting in the Great War. St Louis-born poet T.S. Eliot settled in Britain and wrote in ‘The Wasteland’ (1922) some of the most powerful verse on the devastation caused by the 1914-18 conflict. ‘Hugh Selwyn Moberly’ was another American expatriate’s devastating poetic indictment of the bloodbath of the Great War. Its author, Ezra Pound, wandered further afield until he abandoned his American loyalties for fascism in its Italian form. But when Pound’s poem was published in 1920, it laid the ground for much of the disillusionment literature to follow. Just savor the bitterness:

IV

These fought, in any case,

and some believing, pro domo, in any case ...

Some quick to arm,

some for adventure,

some from fear of weakness,

some from fear of censure,

some for love of slaughter, in imagination,

learning later ...

some in fear, learning love of slaughter;

Died some pro patria, non dulce non et decor” ...

walked eye-deep in hell

believing in old men’s lies, then unbelieving

came home, home to a lie,

home to many deceits,

home to old lies and new infamy;

usury age-old and age-thick

and liars in public places.

Daring as never before, wastage as never before.

Young blood and high blood,

Fair cheeks, and fine bodies;

fortitude as never before

frankness as never before,

disillusions as never told in the old days,

hysterias, trench confessions,

laughter out of dead bellies.

V

There died a myriad,

And of the best, among them,

For an old bitch gone in the teeth,

For a botched civilization.

The novelist E.E. Cummings gave us a taste of French military stupidity in his ‘The Enormous Room’ (1922). John Dos Passos’s ‘Three stories’ (1921) has the same anti-war slant as Ernest Hemingway’s account of the Italian retreat from Caporetto, ‘A Farewell to arms’ (1929). This novel was made into a successful film, starring Gary Cooper and Helen Hayes, and released in 1932. It has been remade three times in subsequent years.

Gary Cooper took on the mantle of a First World War soldier yet again in 1941, when he played Sergeant Alvin York, the most decorated soldier in the American army. A hillbilly pacifist and sharpshooter, he tried to avoid military service as a conscientious objector, but failed to do so. On 8 October 1918, he managed to destroy a German machine gun position and capture 132 German soldiers. What better way for a screen star to bring home to the film-going public the need to prepare for entry into the Second World War?

In popular culture, the Great War left its imprint in gramophone and sheet music. The Irish-American song-writer and tenor George M. Cohan inspired patriotism in his iconic ‘Over there’. It was rendered operatic by the great Italian tenor Enrico Caruso, whose version sold by the tens of thousands too. Its brash, optimistic bravado spoke for and reached many more people than did all the anti-war poetry produced in the shadow of the war.

‘Screen Memories’

Since 1941, the First World War has been eclipsed by the Second World War in the national pantheon of American military history. This is hardly surprising. Pearl Harbor is American territory, and the fight against the Japanese entailed a bitterness the war of 1914-18 rarely engendered. The fight against what was deemed the more dangerous enemy, Nazi Germany, came first, and has left its mark on screen and literature alike. Without the narrative of the heroic cause of either North or South in the Civil War, and without the scale of casualties in the Second World War, in which six times more American men (300,000) were killed in combat than in the First World War, the 1914-18 conflict has faded into the background of American narratives of war and peace.

Recent Revival Of Interest

Since the Vietnam War, many people have found echoes of that conflict in the First World War. Futility in Vietnam had a precedent in futility in the 1914-18 war. This was made visible in Maya Lin’s Vietnam Veterans’ Memorial Monument in Washington, a design derived from her study of First World War commemorative forms. The English scholar Paul Fussell, reacted to the Vietnam War by writing an extremely influential study of First World War writing, The Great War and Modern Memory (1975), which won the National Book Award in that year.

The citizens of Kansas City, Missouri, received Congressional approval in 2004 for their plan to redesign the First World War memorial built in the 1920s as the National World War One Museum at Liberty Memorial. They funded the project through a municipal bond issue, and opened the site in 2006. It has been very successful in stimulating regional and national interest in the war, in particular in the lead up to the centenary of the war’s outbreak in 1914.

No one knows what the Federal Government will do to mark the centenary of the entry of the United States into the war in 2017. There is no national movement of families, with the letters and photographs of soldiers, to press Congress to act. There is no sense that the men who fought the war of 1914-18 were ‘the Greatest Generation’. Instead, it is likely that the centenary moment in the United States will be marked with piety rather than with passion. Like memories of the Korean War, in which fewer American soldiers were killed than in World War one, memories of the 1914-18 conflict probably will be limited to the families of those who served and who lost their lives.

There is one important exception. There is a thriving Armenian diaspora scattered across the United States, whose ancestors were among the more than 1 million victims of the Armenian genocide of 1915-16. The Ottoman Empire’s ruling triumvirate feared the ‘disloyalty’ of Armenians who had been persecuted for decades before the war. In April 1915, entire communities which had lived in Anatolia for one thousand years were forced from their homes and deported to the Mesopotamian desert. Rape, pillage, and murder decimated those forced into exile; desert conditions did the rest. Some thousands of women saved their lives by conversion and entry into Muslim families. The rest perished by the hundreds of thousand. Survivors scattered throughout the world, many in Boston and Los Angeles. They have urged both local and federal authorities to challenge today’s Turkish regime to admit that what happened to the Armenians was genocide. To date, no American president has obliged. Here is a matter which will force attention back to the Great War and one of its most somber chapters.

Author

Jay Winter

Jay M. Winter is the Charles J. Stille Professor of History at Yale University. He receiv…

Learn more