Son of the Midwest

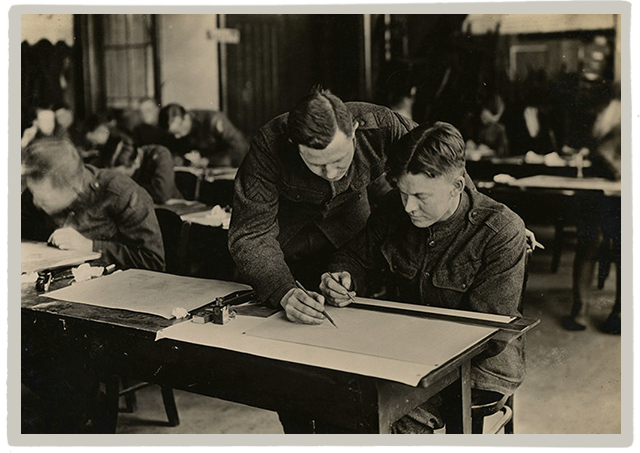

Walt Disney at age 16, standing next to an ambulance he illustrated.

Walt Disney, whose working-class parents struggled to make a living, spent much of his boyhood on the move. He was born on December 5, 1901, in Chicago, Illinois. His first name honored the preacher of the local Congregational church, of which his parents were devoted members, while his middle name, Elias, came from his father, a carpenter and occasional lay preacher. Only a handful of photographs have survived from his infancy, but one depicts the nine-month-old Walt seated on a wicker fan-back chair in a frilly white baby gown and slippers, looking curiously out at the camera. His older brother Roy remembered pushing him along the street in a baby carriage and buying him small toys with his odd-job earnings. Elias Disney worked as a small-time contractor, building houses throughout the city. His wife, Flora, helped her husband by drawing construction plans and keeping the books while managing a bustling household of five children. She had designed the family’s modest two-story house at 1249 Tripp Avenue in northwestern Chicago, and Elias had built it.

By the time Walt was nearly five years old, his parents had grown increasingly wary of life in the big city. Elias, especially, had become uneasy. In part it was a matter of crime, noise, and overcrowding, which disturbed his hopes of tranquility and advancement for his children. But it was also a case of Elias’s notorious wanderlust. Since young manhood he had roamed the country, searching for success in a variety of jobs: railroad machinist and carpenter in Colorado, farmer in Kansas, hotel proprietor and orange-grove owner and mail carrier in Florida. By the time of his retirement, he would have moved at least five more times throughout the Midwest and on the West Coast. His decade and a half in Chicago was a record for staying put, and he began searching for a new location for his family and a new path to success.

Early in 1906, Elias decided to turn again to farming. His brother, Robert, owned several hundred acres near Marceline, and several other relatives lived nearby, so Elias purchased the farm of a recently deceased Civil War veteran and in April the Disney family settled into a small, one-story white house set on forty-five acres of land. It was a multiuse farm, with both crops and livestock, and Elias and his three older sons – Herbert, Ray, and Roy – began the backbreaking labor of planting corn, wheat, and sorghum and raising hogs, cattle, and horses. The work of the traditional farm wife, with its constant round of cooking and baking, preserving food, washing clothes, gardening, and churning butter, proved no less taxing for Flora.

Walt, too young to do much useful work, had the run of the place. He romped in the surrounding fields and woods and encountered birds and wildlife of all kinds. The boy loved to splash in local creeks and play in the farm orchard, and he grew especially fond of watching the Santa Fe trains as they passed on the tracks a short distance from his house. He often had the companionship of a small Maltese terrier – “He was my pal,” he said some fifty years later – or a small pig named Skinny he raised with a baby bottle. Both pets followed him everywhere. In later years, Walt loved to tell stories of his heroic hog-riding exploits during these years: apparently he would jump on the back of his father’s sows and ride them around the barnyard until they dumped him off in the nearby pond. He also began school, attending Marceline’s Park School, where he learned the rudiments of reading, writing, arithmetic, and geography.

This carefree, even idyllic time was not destined to last. Elias’s farming endeavor floundered within a few short years, and the failure could be traced to a number of sources. Angered by their father’s moral strictness, demands for unrelenting labor, and tightfistedness, Herbert and Ray left the farm after a couple of years to make their own way, returning to Chicago and later going to Kansas City. Moreover, Elias was simply not a very good farmer. Refusing to use fertilizers, he managed to produce only small harvests, and he was unable to tailor his crops to the market. Illness proved to be the final straw. In the winter of 1909-10, he caught typhoid fever, then fell victim to pneumonia and was unable to do any framework at all. In early 1910 he was forced to sell his farm at auction – he barely got back what he paid for it – along with all of his livestock and equipment. This event was heartbreaking for the younger Disneys, especially Walt, who saw his familiar rural world disappear on the auctioneer’s block.

This time Elias Disney headed to Kansas City, and the family settled in the late spring of 1910, after the younger children finished school in Marceline. Opportunity seemed bright there; at the eastern edge of the Great Plains wheat belt, Kansas City was emerging as a major livestock trading center and beginning a period of rapid growth. Because of his age and relatively poor health, Elias was unable to pursue strenuous physical labor, but he was able to purchase an extensive newspaper distributorship, delivering the Times in the morning and the Star in the evening and on Sundays to some seven hundred subscribers.

For eight-year-old Walt, this was the start of a difficult era. While Elias managed the operation, his two younger sons did the lion’s share of the actual work. Roy and Walt rose every morning around three-thirty. They spent the next several hours folding and delivering them on foot and by hand; their father forbade them to throw the papers from bicycles and insisted that they place them on subscribers’ porches or behind their screen doors. Rainstorms in the spring and blizzards in the winter added to the burden, and, of course, the boys attended a full day of school after this work. Roy followed the example of his older brothers and left home in 1912, but Walt was stuck. He endured this bone-wearying schedule for six years. Living in Kansas City, however, brought more than work to the boy. A bright and creative, if not particularly scholarly student, Walt attended Benton Grammar School. He had demonstrated a flair for drawing since his Marceline days and now began to attend art classes for children at the Kansas City Art Institute. He supplemented this talent with a new interest in performing and entertainment. Something of a natural ham, he became close friends with a classmate named Walt Pfeiffer, and the “Two Walts” formed a youthful partnership, specializing in performing comedy skits and crude vaudeville routines for friends and at a small local theater.

Young Disney graduated from Benton School in June 1917 with a vague hope of combining his interests in drawing and comedy in an interesting new field: cartoons. Once again, however, his father’s lust for mobility and success disrupted the family. As the newspaper distributorship was providing only a minimal living in Kansas City, Elias chanced upon a business opportunity back in Chicago. An acquaintance approached him with an offer to invest in the O-Zell jelly factory, where, in return for his entire life savings, he could become part owner and head of construction. Elias leaped at the chance and moved his family back to the banks of Lake Michigan in late spring 1917.

This time, however, Walt gained his first breath of freedom. He remained behind for the summer to work on the Santa Fe Railroad out of Kansas City. It was one of the happiest periods of his life. Gaining a position as a “news butcher” with the Van Noyes Interstate News Company, he sold newspapers, popcorn, peanuts, fruit, cold drinks, and other snacks to passengers. He worked funs out of Kansas City into half a dozen states, and he loved it. Talking with grizzled old railroad veterans – engineers, firemen, baggage men – and wearing an impressive blue uniform with gold buttons, he fell prey to the romance of the railroad. He visited dozens of new towns, stayed overnight in boarding houses, and had a number of minor adventures. It mattered little that he made practically no money. It was with considerable reluctance that he left this summertime adventure to join his family in Chicago, and he did so with a new sense of independence and a feel or life’s possibilities.

When Walt entered Chicago’s McKinley High School, in the fall of 1917, he combined his new sense of self-reliance with his old creative urge in a renewed enthusiasm for drawing. He drew cartoons for the Voice, McKinley’s student newspaper, attended classes several nights a week at the Chicago Institute of Art, and made the acquaintance of cartoonists for the Chicago Herald and Tribune. He also began attending vaudeville shows to assemble a file of the best jokes and gags. In order to assuage his father’s suspicions about the entertainment world, he worked a number of jobs to contribute to the household income: handyman and night watchman at the jelly factory, gateman for Chicago’s elevated railway line, delivery boy for the post office. By fall of 1918, however, a new adventure loomed on the horizon.

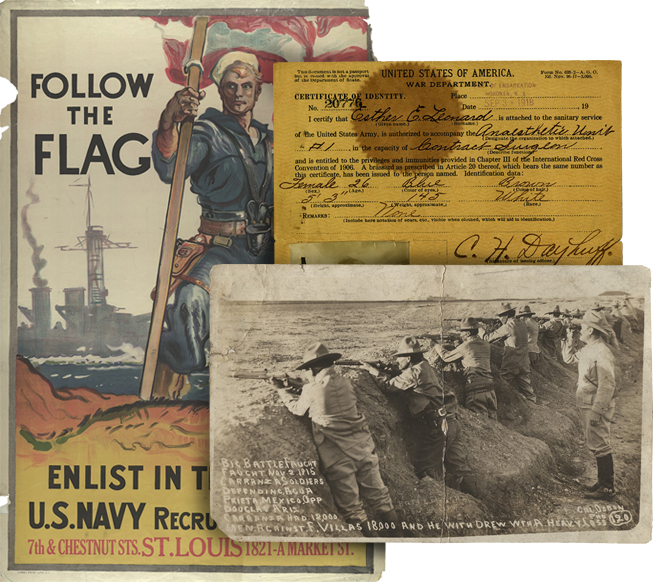

Walt had been intensely jealous when Roy had enlisted in the navy and gone off to fight in World War I. Eager to get out of high school and into uniform, the younger brother first planned to cross the border and enroll in the Canadian army, which was accepting younger recruits than the U.S. Army. When that ploy failed, he began to explore the possibility of joining the Red Cross Ambulance Corps. He learned that while the outfit accepted volunteer drivers aged seventeen and above, it also required passports and parental signatures of approval. Sixteen-year-old Walt implored his parents to sign, but his father refused because he was opposed to the war and already had three sons in the armed forces. Flora was more supportive. She believed that Walt would simply run off if they refused, so she forged Elias’s name on the passport application while her son moved his birthdate back a year. After this deception, the young man was accepted into the American Ambulance Corps and embarked on a great adventure.

Walt Disney was never in physical danger during his World War I service. Indeed, the armistice had been signed and the fighting was over before he left a harbor in Connecticut for France. Nonetheless, the young Midwesterner experienced an entirely new world during his ten months in Europe. His official duties consisted of driving Red Cross supply trucks and ambulances, doing rudimentary repair work on these machines, and providing a taxi service for army officers. He spent some time in Paris and served at an evacuation hospital and then a Red Cross canteen in the French countryside. Eventually he became something of a guide for visiting dignitaries and chauffeured several guests through parts of France and the Rhine Valley in Germany.

Throughout his tour of duty, young Disney avidly pursued cartooning. He sent drawing s to his high school newspaper and submitted cartoons to the leading humor magazines, Life and Judge (they were rejected). He drew posters for the Red Cross and sketches for his friends, and he decorated several vehicles with figures of various kinds. Walt also pursued some new forms of recreation that his straitlaced parents would have frowned upon – drinking, smoking, and card playing – and at some point he purchased a German shepherd puppy. Yet he remained the dutiful son in many respects, avoiding sexual temptations of Frenchwomen and sending a portion of his salary every month to his mother for safekeeping. When the last American troops left and the American Ambulance Corps was disbanded in September 1919, he booked passage home. Walt Disney had left home a boy and returned a young man. Arriving in Chicago taller and heavier, and with considerably more worldly experience, he immediately felt constrained. High school seemed impossibly juvenile after a stint in Europe, and his father’s offer of a job at the jelly factory was scarcely more appealing. Walt had determined to make his way as an artist, in one fashion or another, and a few weeks in Chicago convinced him that opportunity lay elsewhere. He made one of the truly significant decisions of his life – to return to Kansas City and seek his fortune as a cartoonist.

The facts of Walt Disney’s youth are fairly well known, but their significance remains elusive. On the surface, his early years presented little that was particularly noteworthy. The events of his youth were fairly typical for a Midwestern boy in the early 1900s, and seemingly they could have happened to anyone and given rise to any number of adult careers. Beneath the surface, however, several trends offer keys to his sensibility.

Childhood had seen the emergence of several basic personality traits. Even as a youngster, Walt Disney impressed friends and family with his mischievous curiosity and fun-loving nature. His younger sister Ruth, for instance, noted that her brother had had an engaging personality as a boy and “was always thinking of ideas.” As a matter of fact, she confessed, even later in life “Walt always seemed like a kid to me.” Restless creativity and a hankering for the spotlight were apparent even in grammar school. A classmate remembered when Walt, a sixth-grader, went to school on Lincoln’s birthday dressed in a suit, a homemade stovepipe hat, and a fake beard and recited the Gettysburg Address from memory. The principal was so impressed that he hauled Walt around to every class in the school for a repeat performance. At home, the boy was a committed prankster. Once he dressed in his mother’s clothes, went around to the front door pretending to be a neighbor, and engaged Flora in conversation before she realized who it was. Another time he discovered a small rubber bladder that could be inflated with a straw to make things rise, and he startled his mother one afternoon by making her pots seem to rise of their own accord from the kitchen table. When he came home from Europe, he tried to convince his parents that he Rock of Gibraltar had been adorned with a giant lighted Prudential Insurance sign. The gag-filled, merry cartoons of Mickey Mouse and Donald Duck were but a short step from such boyish escapades.

Those cartoons also drew on another youthful source: Walt Disney’s early blending of art and entrepreneurship. He demonstrated a talent for drawing at an early age. In Marceline, for example, he sketched Dr. Sherwood’s prize horse and was overjoyed to receive a quarter in return. Not long after that he infuriated his parents by painting pictures on the side of their farmhouse with roofing tar (he thought it would wash off). His brother Roy recalled that their aunt Maggie, who was enamored of Walt from the time he was a little boy, kept him supplied with pencils and Big Chief Indian tablets of paper. A bit later, in Kansas City, when Walt was around nine years old , he drew a flip book of crude animation for his sister when she had the measles. Another time he stayed up all night making an elaborate drawing of the human circulatory system for a class assignment, and it was so good that he teacher thought he had traced it.

At the same time, the boy’s talent and his commercial sense began to merge. His friend Walt Pfeiffer clearly remembered several examples of this: young Disney drawing illustrations for the Benton School newspaper, drawing advertising cartoons for a local barber in return for free haircuts, earning money by peddling hand-drawn advertisements to local merchants. During Disney’s days in the ambulance corps in France, this instinct became more highly developed. He painted decorations on his comrades’ jackets for ten francs a job. He also developed a commercial concern with a friend remembered only as “the Georgia cracker.” Shrewdly observing the market for war artifacts, the two got their hands on a supply of German army helmets, and after the cracker put a bullet hole in each one, Disney painted them with phony camouflage. Banging the helmets with rocks and rubbing them in dirt to complete the deception, the partners made a tidy profit from these “genuine” relics of the war.

Yet Disney’s entrepreneurial sense also adhered to a rather complex work ethic that clearly arose from a childhood of hard labor. Curiously, although he was consistently described as a workaholic in his adult life, he evolved in his early days a pronounced aversion to physical labor. This is not to say that he was lazy. Far from it, as his abundance of youthful jobs certainly demonstrated. His sister once recounted a story of how Walt was turned down for a summer job at the post office because of his age; he went home and subtly penciled age lines on his face, borrowed his father’s overcoat and hat, and went back and got the job. The determination to succeed was certainly not the problem.

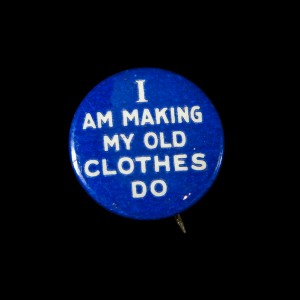

But in a series of interviews in the mid-1950s, Disney recalled at great length the pain he suffered during his years of newspaper deliveries. He described falling asleep in the early morning hours behind stacks of newspapers and being so cold in the winter that he would cry when no one was around. Indeed, he claimed to have a recurring nightmare rooted in this trauma. As he told an interviewer, he still dreamed “that I have missed customers on my [newspaper] route…And I wake up and think, gosh, I’ve got to hurry and get back…It’s the darnedest thing.” Because of this regimen, Disney said, “I never had any real play time.” In fact, when he got married, in 1925, he told his bride that lawn work and gardening were out of the question, because “I just did too much of it as a kid, and I just didn’t want to do it.” Even as a young man he made it clear that creative work, rather than the grind of physical effort, would pave his way to success.

Young Disney carried into adulthood two other attitudes that shaped his course in important ways. First, he rejected the extreme piety of his parents. Flora and particularly Elias were rather strict Congregationalists, and faithful churchgoing was the rule in the Disney family. Walt rebelled, not by turning to disbelief but by relaxing his whole attitude toward religion. His daughter Diane explained how he would drop her and her sister at the Christian Science Sunday school and pick them up later, saying, “He had an intensely religious youth. He’d been brought up in a strictly regimented church atmosphere. His father was a deacon at one time. Reading this and knowing this now, I can understand why he had such a free attitude towards our religion. He wanted us to have religion. He definitely believed in God. Very definitely. But I think he’d had it [with organized religion] as a child.”

Second, Disney learned to detest the burden of poverty. Thinking back to his family’s struggle for economic survival in Kansas City, he remembered going door-to-door with a pushcart, helping his mother peddle country butter in various neighborhoods to help meet expenses. “But it was embarrassing at times,” he said, “because I went to school with the kids that lived there, you know? They were kind of…wealthy children.” Much later, a friend at the Disney Studio noted that his boss “had this craving for ice cream sodas and candy bars because as a kid he couldn’t afford them.” Walt had colorful jars of candy all over his studio office and constantly offered some to visitors. At home, he built a huge soda fountain in his club room, complete with all the attachments and extras. According to a friend, “He’d get behind the fountain like a soda jerk and fix these huge goopy things for his guests, ice cream sodas and the biggest banana splits you ever saw. He loved doing that. He loved having that soda fountain because as a kid he couldn’t spend money for ice cream. His youth was scratching for pennies and nickels and tossing whatever he earned into the kitty at home.”

Disney’s ten months in France, he was fond of telling friends, constituted “a lifetime of experience” that was valuable beyond reckoning. In fact, his whole notion of education flowed from this episode. “I think I got a greater education by [serving in the ambulance corps] than you can ever jam into anybody by going through this methodical business of going to school every day,” he speculated. “You can’t force people to be scholars … There’s other ways that people get educated.” Military experience, he argued, had provided maturity and worldly wisdom at a young age and taught him to “line right up on an objective. And I went for it. And I’ve never had any regrets.” For this extremely creative man who never graduated from high school, childhood had shaped a certain viewpoint: the world was a series of obstacles, and education meant taking classes in the school of hard knocks. Practicality and experience beat out abstraction any day.”

Reprinted from The Magic Kingdom: Walt Disney and the American Way of Life, “Son of the Midwest” Steven Watts, ed., by permission of the University of Missouri Press. Copyright© 1997 by the Curators of the University of Missouri. http://press.umsystem.edu/product/The-Magic Kingdom,1656.aspx

Author

Steven Watts

Steven Watts is a professor of history at the University of Missouri. He specializes in t…

Learn more