Missourians on the Border

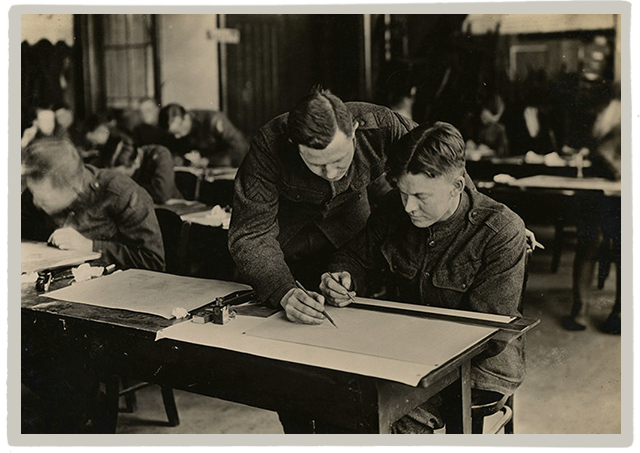

Soldiers in a trench on the Mexican border - November 4, 1916

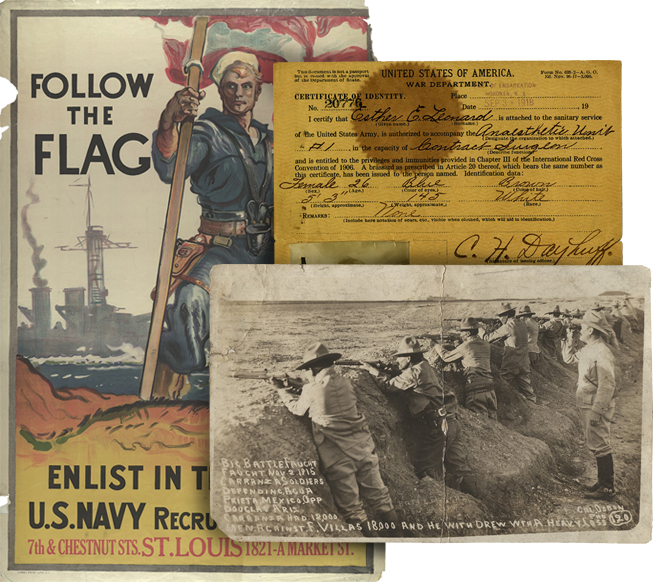

Early on the morning of March 9, 1916, Mexican irregulars under the command of Francisco “Pancho” Villa charged into the border town of Columbus, New Mexico. After a nearly three hour clash with the town's citizens and U.S. cavalrymen, Villa’s men retreated back across the border, leaving behind 18 dead Americans.

An outraged President Woodrow Wilson ordered General John J. Pershing to lead two columns of U.S. Regulars in pursuit of the bandit Villa. On June 18, 1916, Wilson, citing “the possibility of further aggression upon the United States” from Mexico and the “necessity for the proper protection of that frontier,” mobilized the entire United States National Guard for duty on the Mexican border.

Secretary of War Newton Baker's telegram calling out the National Guard of Missouri reached Governor Elliott W. Major on the evening of June 18. Elliott then called National Guard commander Brigadier General Harvey C. Clark and ordered him to assemble the state’s troops. By early the next morning, individual Guard companies were assembling in their hometowns. A mere twenty-four hours later, the first of more than 5,000 men began gathering at the State Rifle Range near Nevada to form the First Missouri Brigade. By June 23, the entire force (four infantry regiments, a battalion of field artillery, a field hospital, an ambulance company, a troop of cavalry, and a signal corps company) had arrived, and Missouri became the first state to complete its mobilization.

National Guard veterans and raw recruits, "city dudes" from Kansas City and St. Louis, and "toughened boys from the farms and mines" were given physical examinations and were formally mustered into federal service.1 "Some companies were very good, some were very bad," in drill, appearance, and discipline, admitted one Guardsman, and "more were mediocre."2

After a brief stay at Camp Clark, the eager Missourians boarded trains for the Texas border. As they rode through Texas, the National Guardsmen noted a “warlike aspect,” with patriotic civilians treating the soldiers to food and drink, Regular Army guards stationed on railroad bridges, and Mexican refugees fleeing northward. All the Missouri guardsmen reached Laredo, Texas by July 10 and established camp outside town.3

Laredo and its environs presented a novel sight to the men from Missouri. With an estimated population of 30,000, of which no more than two or three thousand were white, Laredo was "practically a Mexican town," wrote General Clark. The situation was much the same across the river in the town of Nuevo Laredo, "a city of considerable commercial importance," that included a garrison of Mexican regulars. The country outside of Laredo was sparsely settled, with a number of small hamlets of Hispanics. "The country is rough with no timber except small patches of mesquite," explained General Clark, "and is generally desolate and uninviting."4 In addition, the area’s sand storms, insects, reptiles and intense heat tested the spirits of the troops. Drinking water obtained from the Rio Grande had to be boiled before drinking, and only the addition of lemons made it palatable.5 On the evening of August 18, the unpredictable south Texas weather unleashed torrential rains and 20-60 mile per hour winds, knocking practically every tent down and subjecting the Missourians to a punishing storm until 4 o'clock the following morning.6

Despite the hardships, the Missourians quickly settled into the routine of army life in Laredo. One private wrote that "Uncle Sam is breaking us in as fast as it can be done. We have done and are doing all that an army is expected to do, except fight and we will soon be ready to do that." Roll call, sick call, police call and formal retreat ceremonies helped convince the Guardsmen that they were in a real military camp. In addition, drills, reviews, camp, outpost and scout duty and target practice helped fill the day. Wednesdays and Saturdays were "hike days," in which blankets, spades, axes and picks were carried for an eight or ten mile "stroll." The physical exertion paid off as soon the Missourians were able to boast of their prowess: "I can march ten miles dig a trench and do most anything else all day and still feel like a prizefighter," claimed a private in the Second Missouri.7 St. Louis newspaper reporter Clair Kenamore was impressed by the Missouri men, who “stand well, walk well and handle themselves like soldiers, but they are ineradicably Missourians.”8

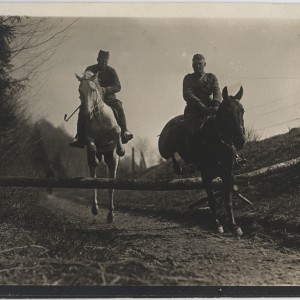

The presence of Mexican soldiers across the river and the likelihood of a bandit raid helped remind both officers and men that they were in hostile country. Details were sent to guard fords or bridges around Laredo or sites in the city itself. On August 9, a marksman on the Mexican side shot twice at a sentry from the Second Missouri, and the Missourian fired one shot in return. The exchange caused a great deal of excitement, as the Mexican troops withdrew to a house and the American guard was increased. Although both sides exchanged friendly waves as the Mexican cavalrymen came to the river to water their horses, it was clear that "each side, loaded rifles in hand, keenly watches every move the other makes,” noted a soldier, and “a rifle carelessly raised or a shot accidentally fired might be the signal for hostilities to start."9 One Missourian believed that due to the terrible conditions on the other side of the border, it was only a matter of time before hostilities would commence. “Sooner or later we must invade Mexico,” he believed, for if they did not “straighten things out there” they would “always have trouble.”10

Major redeployments changed the mission of the First Missouri Brigade in September 1916. The First and Third Missouri Infantry regiments left the border to return to Missouri, while the Second Missouri was ordered to take over patrol duties of the Laredo District, a 145-mile section of the border on either side of Laredo. The plan was to guard all the river crossings, so companies were scattered along the river at various locations, at ten to fifteen mile intervals, and in strength from one platoon to two companies, depending on the importance of the crossing. Telephone lines linked each station with Laredo, patrols were sent out to maintain communications, and trucks brought supplies from Laredo to the outposts. Drill sessions were kept to a minimum as guard duty filled the day, although some outposts devoted time to building entrenchments to fortify their camps.

Finally, on October 17, the Second Missouri was relieved from duty by the Fourth and returned to Laredo. The Fourth Missouri remained on the district river patrol until November 26. General Clark proudly pointed to the fact that not a single case of disorder or a single hostile crossing of the river had taken place while his men were manning the outposts.

Perhaps the most exciting event of the Missourians' border campaign came in the early part of December, when all the troops in the Laredo District, including the Missourians, were ordered to take part in a "field problem." General Clark’s men opposed a regiment of Florida National Guard and some Regular cavalry and artillery units. After a twenty-five mile march in below freezing temperatures, the Missourians were given their orders for the exercise. The hypothetical problem stipulated that enemy forces held Laredo, and that hostile troops were between Clark's men and the city. General Clark was to march to and capture Laredo and hold it before enemy reinforcements could arrive from San Antonio. Clark moved his men toward Laredo and managed to force his enemy back before making camp for the evening. The following morning, with the Second Missouri in the advance, General Clark's force outflanked the enemy's artillery and captured one of their batteries. Clark was then able to flank and rout the Florida National Guardsmen and the remaining artillery and open the road to Laredo.

A victorious Clark wrote that the fifty mile tactical exercise "was interesting and furnished some experience and considerable excitement for the men," but did not afford much instruction to his officers. The enemy had not taken full advantage of all opportunities, the Missouri general explained, and his success was largely due to the "carelessness or oversight of the opposing force." Nevertheless, Clark was forced to admit that his men took advantage of their opportunities and did all that could be done.11

Finally, in mid-December, Clark received orders to begin sending the remaining units of the First Missouri Brigade home. The first contingent left Laredo on December 19, while the final Missouri unit bade farewell to the city on February 20, 1917.

Although relieved to home, the Missouri Guardsman enjoyed a sense of accomplishment from the months spent on the border. One soldier from Columbia reported that although the “boys” saw no actual fighting, they had “lots of scares,” and when the call to arms was sounded they were “in the trenches, loaded for bear, in about six seconds flat.” Their time in active service had transformed them. “Five months of clean out-door life and plenty of exercise make pretty fair soldiers,” he concluded.12 The Joplin News-Herald noted that the local company stepped off the troop train and "marched in real military fashion, with assurance and the true swagger."13 The Missourians were given official tributes by Secretary of War Baker and the Missouri State Legislature, but perhaps their commander, General Clark, bestowed the finest accolades. In his official report of the Guard's service, he wrote that "the State might well be proud" of the performance of the troops in Texas. Although they all desired to return home, Clark's Missourians "took advantage of the opportunity for training and after two months' service . . .they were thoroughly hardened and I do not believe there is today a finer body of troops in this country than the Missouri National Guard."14

When war was declared on Germany in April 1917, many of the Mexican Border veterans could be found in the ranks of the Missouri National Guard. The duty in Texas had "seasoned" the majority of the men, one Springfield newspaper editor believed, and helped them "quickly fit themselves for whatever duty" as they prepared to meet the enemy “over there.”15 Many Missourians who had guarded the border with General Clark went to their training camps in 1917 not as raw recruits, but as experienced, disciplined citizen-soldiers.

1 Springfield (MO) Leader, July 3, 1916.

2 Patrick, Jeffrey L., ed., Guarding the Border: The Military Memoirs of the Ward Schrantz, 1912-1917 (College Station: Texas A&M University Press, 2009), 94.

3 History of the Carthage Light Guard, Ward Schrantz Collection, Jasper County (MO) Record Center.

4 Missouri Adjutant General, The Service of the Missouri National Guard on the Mexican Border (Jefferson City: The Hugh Stephens Co., 1919), xi.

5 Joplin (MO) Globe, July 13, 1916.

6 Joplin (MO) Globe, August 20, 1916.

7 Springfield (MO) Republican, August 24, 1916.

8 Springfield (MO) Leader, July 18, 1916.

9 History of the Carthage Light Guard, Ward Schrantz Collection, Jasper County (MO) Record Center.

10 University Missourian (Columbia, MO), July 23, 1916.

11 The Service of the Missouri National Guard on the Mexican Border, xii-xv, xl.

12 The Daily Missourian (Columbia, MO), November 16, 1916.

13 Joplin (MO) News-Herald, January 15, 1917.

14 The Service of the Missouri National Guard on the Mexican Border, xvii.

15 Springfield (MO) Leader, May 6, 1917.

Author

Jeffrey Patrick

Jeffrey Patrick is the librarian at Wilson’s Creek National Battlefield in Republic, Misso…

Learn more

Related Articles

Related Collections

Smith, Richard Thompson Collection

Richard T. Smith joined Company A of the Signal Corps, Missouri National Gu…

Wiggins, Edwin Collection

Sgt. Edwin Wiggins of Carthage, Mo. was a National Guard soldier in Company…

Schrantz, Ward Collection

This collection consists of the memoirs of Ward Loren Schrantz of Carthage,…