America Joins the War

Soldiers posed with guns - n.d.

In 1914, most Americans blamed the outbreak of the war either on the overly-aggressive actions of Germany or the essentially undemocratic nature of many of the belligerent governments. In 1914, few Americans wanted to see their nation become directly involved in the war, but most Americans who did not blame both sides equally sympathized with the Allies. They sent money, medical supplies, and sometimes went themselves as volunteers to help Britain and France. As the war evolved, Germany’s defenders in the United States became fewer and fewer until by 1917 the American people had come to see the need to fight against Germany to protect both the future security of Europe and the United States itself.

Most Americans took a nuanced attitude toward Germany’s role in causing the war. They blamed the German (or, in some formulations, Prussian) elite for having begun a war not in the interests of the German people. They generally saw the German people as victims of their own unrepresentative form of government. From early on, therefore, Americans saw the reform or abolition of the current German government as an important desired outcome of the war. Democratic governments, they argued, would not have gone to war as the autocracies had done in 1914.

Germany had some defenders in the United States, although they always remained in the minority. Some cities had large German populations and much of the German-language press took up Germany’s cause. Many, though by no means all, German-Americans blamed Russia for the outbreak of the war and urged the United States to remain neutral or to pressure the British and French to make peace. Some Irish-Americans and most Jewish-Americans also supported the German cause, at least at first, because of their hatred of England and Russia, respectively.

As the war evolved, almost all American attitudes became increasingly more anti-German. Americans reacted with anger at German atrocities in Belgium. Pro-Allied journalists surely inflated some of those incidents, but there were also enough real, verifiable atrocities in Belgium to incite American ire. Americans also knew that Germany was running a highly-sophisticated spy ring in the United States that included schemes to smuggle firebombs onto American ships and blow up railroads to Canada. Actions like these eroded the support that some Americans had previously been willing to give to the Germans.

Americans were also dependent on the British for financial and economic security. The start of the war devastated the American economy as the United States suddenly found itself cut off from British credit, shipping, and insurance. Once the initial shock had worn off, Americans came to understand that their economic recovery depended in large part on trade of all kinds with the British and the French. Some Americans even understood as early as the war’s first few weeks that the war might result in a permanent shift of economic power from London to New York as the Europeans needed to borrow money and buy American raw materials and finished products of all kinds in unprecedented numbers. The New York Tribune ran a headline in October, 1914 that read “War May Make New York the Financial Capital of the Earth.” Thus did American financial and political interests come into alignment with one another.

The sinking of the passenger liner Lusitania in May, 1915 forced Americans to come to grips with the war on an entirely new level. The death of 128 Americans, including six from Missouri, opened a debate about how the United States should prepare for war should it come. At the very least, many Americans wanted to see a strengthened army, navy, and merchant marine to protect America from further encroachments on their neutrality. Others, like the isolationist secretary of state William Jennings Bryan, argued for further separating the United States from Europe’s quarrel, even if that meant banning Americans from traveling overseas.

President Wilson chose the middle ground, keeping American options open, but forcing the Germans to modify their submarine warfare policy. Bryan resigned, believing that Wilson had gone too far in abandoning American neutrality. Most Americans supported Wilson, however, happy to stay out of a war few of them wanted, but pleased that the president had made a forceful defense of American rights. Wilson had to repeat the task in March, 1916 when the Germans sank the Sussex, killing more than 50 people.

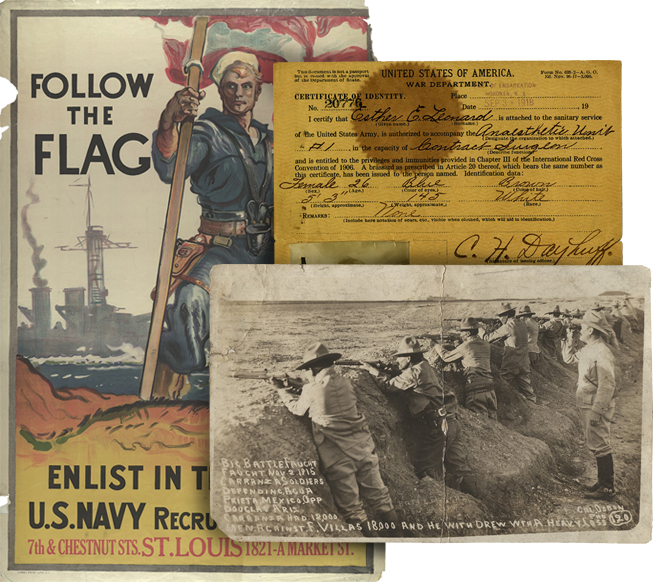

Thereafter, American attentions largely drifted away from Europe. Tensions with Mexico rose to the fore as Wilson dispatched troops, including the Missouri National Guard, to deal with instability there and Mexican rebel leader Pancho Villa raided Columbus, New Mexico. Wilson won the razor-thin election of 1916, but neither he nor his challenger, Charles Evans Hughes, made the war in Europe a priority on the campaign trail. They sought instead to keep the focus on domestic issues.

Tensions with Germany rose again, however, in early 1917. In an attempt to win a war that seemed to have little end in sight, the Germans reintroduced Unrestricted Submarine Warfare, meaning that more ships with Americans on board would soon be at risk. Wilson knew that he would have to respond in some way. Then came the release of the Zimmermann telegram, a message sent from Germany’s foreign minister, Arthur Zimmermann, to Mexico that predicted war between the United States and Germany once the Germans resumed submarine warfare. When it did, the Germans offered to support Mexico’s reacquisition of the lands it had lost to the United States in 1848 (including Texas, Utah, Nevada, Arizona, New Mexico, and California) if Mexico would invade the United States. The telegram also asked Mexico to bring Japan into an anti-American alliance.

The Zimmermann telegram proved to be the final step in a voyage that had begun in 1914. It seemingly proved all of the fears Americans had about the German government and its intentions toward the United States. In late March, 1917 Wilson’s cabinet unanimously recommended that the president ask the Senate for a declaration of war. He followed their advice in an April 2 speech. The World War was now also America’s war.

Author

Michael S. Neiberg

Michael S. Neiberg is the Henry L. Stimson Chair of History in the Department of National…

Learn more

Related Articles

Related Collections

Clemens Family Collection

The Clemens Family Collection features several letters written by Fritz Von…

Wiggins, Edwin Collection

Sgt. Edwin Wiggins of Carthage, Mo. was a National Guard soldier in Company…